LPP JUNE 2021 VOLUME 22 ISSUE 3000

Addressing 3 Civil Rights Issues in Cuba

For years, Cubans have experienced severe restrictions in their ability

to exercise freedom of speech. While they do not have the same First

Amendment liberties as in the United States, Cubans are fiercely

fighting for their rights to expression, speech and access to online

opinion articles. Change is steadily emerging for Cubans, but the

process has been slow. Here are three civil rights issues in Cuba.

3 Civil Rights Issues in Cuba

- Freedom of Expression. Cuba has restricted freedom of expression through the media for years. The Cuban government has heavy control over the content media outlets can broadcast, as well as the information citizens can view. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Cuba has the “most restricted climate for the press in the Americas.” Journalists and bloggers routinely write about Cuba without restriction, but the Cuban government has the power to block these websites and other channels from their citizens: websites like 14ymedio, Tremenda Nota, Cibercuba, Diario de Cuba and Cubanet have experienced censorship, according to World Report 2020. The situation is difficult to change due to high internet use costs. When a mere 600 MB of space costs $7, private providers struggle to afford the platforms needed to express their uncensored content.

- Freedom of Movement. In Cuba, citizens cannot move freely from one residence to another. They do not have permission to move to a new apartment or house, nor can they change their place of employment. Because private employers are extremely limited in the number of workers they contract, the country experienced unprecedented unemployment numbers in 2019 with 617,974 “self-employed” Cubans. One action that could help secure the freedom of movement for many Cubans is repealing Decree-Law No. 366, which limits non-agricultural cooperatives. Eliminating this legislation would lift restrictions on where Cubans can work and live.

- Due Process. Cubans lack the freedom to protest due to legal regulations. Consequences for minor offenses like public disorder, disrespect for authority and aggression stop people from protesting freely. When police forces can use these loose definitions of illegal activity to arrest protesters, freedom of expression and speech suffer. Measures like repealing Law 88 aim to eradicate false policing and reliance on regulations that “criminalize individuals who demonstrate ‘pre-criminal social dangerousness’ (as defined by the state) even before committing an actual crime,” according to The Heritage Foundation. In essence, this action would reduce protections for unfair legal enforcement of state censorship and ultimately provide Cubans a much-needed avenue for freedom of expression through protest.

Involving NGOs

Acknowledging Cuban citizens’ need for support in securing their civil liberties, United States organizations have begun to intervene. For example, The Global Rules of Law & Liberty Legal Defense Fund (GLA) in Alexandria, Virginia is a legal defense fund assisting citizens who cannot afford legal guidance. The GLA had total revenue of $92,400 in 2018, enabling this NGO to provide legal resources like local councils and political information to communities within multiple Latin American countries including Cuba. By enhancing resources for Cuba’s legal system and due process, actions from groups like the GLA could become significant in helping Cubans secure freedom of expression.

The GLA has helped Cuban journalists like Roberto de Jesus Quiñones Haces, who is serving a one-year sentence for charges of “resistance” and “disobedience,” according to the global liberty alliance. He was arrested for reporting the prosecution of Pastors Rigal and Exposito, who were homeschooling their children in Guantanamo. The GLA recognized this arrest as persecution of the press and agreed to support Quiñones, increasing national awareness of his unjust prosecution by filing a Request for Precautionary Measures with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and publishing a video documenting his story. Since the beginning of his jail time in September 2019, Quiñones and the immorality of persecuting the press have gained widespread attention in both the United States and Cuban legal systems.

Another United States NGO advocating for civil rights in Cuba is Plantados until Freedom and Democracy in Cuba in Miami, Florida. By providing aid to Cubans imprisoned for expressing support for democracy, this organization aims to support freedom and democracy in an environment where these fundamental liberties are largely ignored.

The Future of Civil Rights in Cuba

Thoroughly addressing these three civil rights issues in Cuba could help Cubans finally gain freedoms that democratic nations around the world enjoy. As several United States NGOs have demonstrated, actions like simply sharing news and advocating for change have the potential to encourage progress. In doing so, Cuba has the power to become a model for other developing countries in the fight for civil liberties.

– Grant Ritchey

Photo: Flickr

Cuba’s complicated political history has contributed to the government’s crackdown on free speech and public criticism of the nation. However, protecting political regimes is no excuse for oppression or violent action in any country or political system. Observing and acknowledging the status of human rights in Cuba is essential to improving the living conditions of those who live there. Here are the top nine facts about human rights in Cuba.

Top Nine Facts About Human Rights in Cuba

- Political Protest – The first of the top nine facts about human rights in Cuba pertains to Cuba’s political integrity. The Human Rights Watch reported that the Cuban government uses tactics, such as arbitrary detentions, to intimidate critics. These tactics are also intended to prevent political protest and dissent. In fact, the number of arbitrary detentions rose from a monthly average of 172 to 825 between 2010 and 2016. These unreasonable detentions are meant to discourage Cuban citizens from criticizing the government. Additionally, they result in a serious freedom of speech crisis for the Cuban people.

- Political Participation – Although dissent against the government is punished harshly, more Cubans are willing to express discontent with their votes now than in previous years. For example, during a constitutional vote in 1976, only 8 percent of the population voted that they were unhappy with their current constitution. However, in the most recent constitutional vote, 14 percent of the population voted they were unhappy. Although this is still a small percentage of the country willing to express discontent, it signifies substantial improvement from previous years.

- Freedom House Rating – In 2018, the Freedom House gave Cuba a “not free” rating. This is due to the Cuban government’s use of detentions to restrict political protest and restrain freedom of the press. However, there have been several notable improvements including the reforms “that permit some self-employment.” These economic reforms give Cubans more control over their personal financial growth.

- Right to Travel – There have been improvements in Cubans’ overall right to travel throughout their country and beyond. Since 2003, when travel rights were reformed, many who had previously been denied permission to travel have been able to do so. However, the government still restricts the travel rights of Cubans who criticize the government.

- Freedom of Religion – The U.S. State Department reported that although the Cuban Constitution allows for freedom of religion, there have been several significant restrictions on freedom of religion in Cuba. Accordingly, the government has used “threats, travel restrictions, detentions and violence against some religious leaders and their followers.” In addition, the Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), considered an illegal organization by the Cuban government, reported 325 violations of freedom of religion in 2017.

- Freedom of Media – The internet is limited and expensive in Cuba. Moreover, the Cuban government censors anything made available to the Cuban people. The Human Rights Watch reported that “the government controls virtually all media outlets in Cuba and restricts access to outside information.” While there are a few independent journalists who publish their work online, the Cuban government regularly takes these sites down so they cannot be accessed by the Cuban people.

- Access to Healthcare – Access to healthcare remains strong in Cuba. Despite its economic status, the country has a life expectancy of 77 years. The World Health Organization even reported a drop in child mortality, reporting only seven deaths for every 1,000 children. This is a substantial improvement compared to 40 years ago when there were 46 deaths per 1,000 children. This strong healthcare system is a great success for the country and brings a higher quality of life to its citizens.

- Labor Rights – Cuba possesses a corrupt labor climate. As the largest employer in the country, the government has immense control over labor and the economy. Consequently, workers’ ability to organize is very limited. The state is able to dismiss employees at will. This lack of stability and the constant threat to citizens’ jobs enables the state control that restricts citizens’ rights to free speech.

- Political Prisoners – The Cuban government has wrongfully imprisoned several political dissidents. For instance, Dr. Eduardo Cardet Concepción was sentenced to three years in prison for criticizing Fidel Castro. In addition, a family was sentenced to prison for leaving their home during the state-mandated mourning period for Fidel Castro. However, the children of the family were released from prison after a prolonged hunger strike.

Although the Cuban government has been very successful at providing its citizens with a high quality of health care and is providing more economic freedoms, there are still huge restrictions on speech and media in the country. The government can threaten dissenters with unemployment, restrict their right to travel and arrest them on false claims. These restrictions are a serious human rights violation. In order to help provide the Cuban people with the opportunity to fully have a say in their government, it is important for those outside of Cuba to advocate and raise awareness for the plight of the Cuban people.

– Alina Patrick

Photo: Flickr

Freedom of Expression in Cuba

Since the fall of the US-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in 1959 Cuba has been a one-party state led by Fidel Castro, a devotee of Marxist-Leninist theory who brought revolution to the country and created the western hemisphere’s first communist state.

Fidel Castro’s health has been an issue for some years. In July 2006 the ageing president temporarily stepped aside after undergoing surgery, and on 19 February 2008, Fidel Castro officially handed over control of the government to his brother and designated successor, Raul Castro. His government has continued to employ the totalitarian methods used by its predecessors in repressing independent journalism, though it is now more common for dissidents to be subject to routine harassment rather than major trials.

The Cuban media are tightly controlled by the

government and journalists must operate within the confines of laws

against anti-government propaganda and the insulting of officials which

carry penalties of up to three years in prison. The Criminal Code is the

primary legal instrument used to repress freedom of expression in Cuba.

Freedom of expression is limited by laws that have criminalized

disseminating enemy propaganda, ‘unauthorized news’ and insulting

patriotic symbols. According to figures provided by Reporters Without

Borders, Cuba has the second highest number of journalists in prison

after China.

Around 80 people were detained in Cuba as part of a

crackdown on alleged dissidents that began on 18 March 2003. 35

writers, journalists and librarians were sentenced during one-day trials

held on 3/4 April 2003 under laws governing the protection of the Cuban

state. Political prisoners are held in extremely poor conditions;

reports have shown that they suffer physical and sexual abuse by other

inmates and guards and often do not receive medical attention. Any

criticism of their conditions leads to reprisals in the form of solitary

confinement and restricted visitation rights. According to Reporters

Without Borders, 24 journalists were still serving their prison

sentences as of 2008, most of them imprisoned for threatening “the

national independence and economy of Cuba.”

The Government heavily monitors internet communications. The Law of Security of Information prohibits Cubans from having internet services unless they belong to certain official organisations. The Government has recently been targeting writers that attempt to disseminate information of human rights abuse in Cuba via the Internet.

There is however some civil society activism in Cuba. In May 2006, activist Oswaldo Payá published his proposal for a new constitution, which included greater freedoms for Cuban people. This document was based on the results of his ‘Todos Cubanos’ programme, an initiative that involved consultation with thousands of Cuban citizens.

The Damas de Blanco (Ladies in White) are another important civil society group in Cuba. These wives and family members of political prisoners hold peaceful vigils and marches for the release of their relatives. The Damas de Blanco were awarded the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought in December 2005. They were not permitted by the Cuban Government to travel to collect their award. In October 2006, the Damas de Blanco were honoured with another award- the Human Rights First Prize for 2006.

Most recently, a wide group of key opposition figures, including Oswaldo Paya, Damas de Blanco and Martha Beatriz Roque, have formed an alliance known as “Unidad por la Libertad”.

At a governmental level, there are certainly clear avenues Cuba could follow towards greater political openness. In December 2007, the Cuban government announced its intention to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The ratification, if it occurs, would represent an important break from Cuba’s longstanding refusal to recognize these core human rights treaties. In February 2008, Cuba gave signatures only to these UN treaties.

Since becoming President in February 2008, Raul Castro has implemented only modest social and economic reforms, despite promising more. The Cuban economy also still suffers as a result of the US economic embargo, yet there is little chance of this being lifted while Cuba continues to restrict political freedoms and mistreat its political prisoners.

Nonetheless, the arrival of Barack Obama as the new US President has stirred fresh hopes for the fate of prisoners of conscience in Cuba. Mr Obama said during his election campaign that a scaling back of the US embargo would be possible, but only if concrete steps were taken by Havana towards democracy, including the freeing of political prisoners.

Cuba’s stance in relation to the US has also softened. In a speech in January 2009 Raul Castro said that he would be willing to engage in talks with Mr Obama, yet he still insisted on non-conditionality for such engagement. In general, the Cuban government remains wary of US demands relating to political freedoms or human rights issues, and this could continue to be a sticking point.

There is also hope that greater political openness in Cuba may come since the restoration of co-operation with the EU in October 2008. However, the hope that external diplomacy may eventually translate into greater internal freedoms is for now stifled given that Cuba’s strongest allies continue to be Venezuela, China and Russia.

Patrick Loughran.

Sources: For further information, please see the annual reports from Amnesty International (http://www.amnesty.org/), the Committee for the Protection of Journalists (http://www.cpj.org/), Reporters Without Borders (http://www.rsf.fr/), The Inter American Press Association (www.sipiapa.com) and the International Freedom of Expression eXchange (http://ifex.org/) . See also Human Rights Watch (http://www.hrw.org/). For more general information on Cuba, see the Foreign and Commonwealth Office country profile (www.fco.gov.uk).

Originally posted with the url: www.englishpen.org/writersinprison/campaigns/cubacampaign/Cuba/

Six facts about censorship in Cuba

To mark the World Day against Cyber Censorship on 12 March, here are six things you should know about free speech, the internet and online censorship in Cuba.

The re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the US and Cuba in December 2014 brought renewed hope for an end to the US economic embargo, which has had a dire impact on the human rights of ordinary Cubans. But while tourists flock to the island to experience its romantic, old-world charm before it “changes”, less romantic is its history of restricting freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, still shown in the authorities’ determination to stifle dissent.

1. Freedom of expression can land you in jail in Cuba.

Graffiti artist Danilo Maldonado Machado, known as “El Sexto”, found this out when he was locked up for most of 2015 for painting the names of Raúl and Fidel – the names of the Castro brothers who have been in power since 1959 – on the backs of two live pigs. He had planned to release the animals as part of an artistic performance but, before he could, he was accused of desacato (contempt) and thrown in prison for 10 months. He was never formally charged or brought before a judge.

2. The state has a virtual monopoly on print and broadcast media.

The Cuban Constitution recognizes freedom of the press but expressly prohibits private ownership of the mass media. While independent journalists and bloggers have emerged in recent years, the authorities continue to prevent journalists critical of the government from doing their jobs. On International Human Rights Day 2015, journalists at 14ymedio – established by prominent cyber activist Yoani Sanchez – were prevented from reporting on a protest coordinated by human rights groups The Ladies in White and TodosMarchamos. According to one journalist, state security agents blocked the door to the building they worked in and told him: “Today you are not going out.”

Today only 25 per cent of Cubans use the internet, while only five per cent of homes are connected.

3. Cuba is one of the least connected countries in the Americas.

Until 2008, the government banned ownership of computer and DVD equipment in Cuba. Today only 25 per cent of Cubans use the internet, while only five per cent of homes are connected. Internet access is still prohibitively expensive for most, and far from accessible to all. Cuba has said it will double access in the next five years, with public Wi-Fi hot spots starting to open since March 2015, but it remains the most disconnected country in the Americas.

4. Internet access in Cuba is censored.

With access to internet so limited, online censorship is not that sophisticated in Cuba. Authorities frequently filter and intermittently block websites that are critical of the state. Limiting access to information in this way is a clear breach of the right to freedom of expression, including the right to seek, receive and impart information.

5. Communicating with Cuban human rights activists from overseas is difficult.

Amnesty International, along with many other independent international human rights monitors, including UN Special Rapporteurs, are not allowed to access Cuba. The landline, mobile and internet connections of government critics, human rights activists and journalists are often monitored or disabled. In the lead-up to Pope Benedict’s three-day visit to Cuba in September 2012, a communications blockade prevented Amnesty International and other international organizations from gathering information on a wave of detentions that were taking place. Communicating with Cuban human rights activists remains challenging, particularly at times when the authorities are arresting people based on their political opinion.

6. Cubans are savvy about how to circumvent censorship and government restrictions to internet access.

From underground Wi-Fi, to creating apps, to harnessing the power of USBs, Cubans are finding ways to share information and avoid cyber censorship. World Day against Cyber Censorship is a time to show solidarity with Cuban dissidents, activists, journalists andtheir struggle.

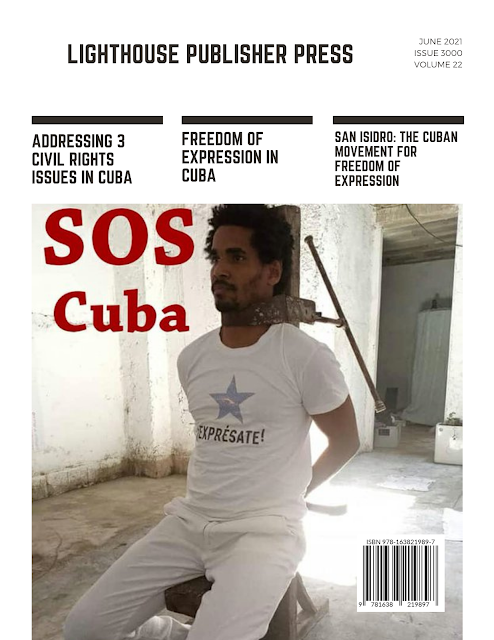

San Isidro: the Cuban movement for freedom of expression

| EDITOR: | Ellen Nemitz, Brazil |

|---|

The arrest and conviction of the Cuban artist Denis Solís – self-described human rights' activist and opponent to the Castro’s regime – sparked a long series of protests, hunger and thirst strikes (according to journalist Abraham Jiménez Enoa, authorities prevented supplies from being received) and repression in Havana, with several demonstrators and supporters detained. Solís was arrested on November 9 and, just two days later, was trialled and sentenced to eight months in prison for contempt, according to Amnesty International.

The first act of resistance was convened three weeks ago by the San Isidro Movement, which gathers artists, journalists and other activists “to promote, protect and defend freedom of expression, association, creation and diffusion of arts and culture in Cuba” – it was created in 2019 to "empower the society toward a future with democratic values," right after the Decree 349 centralised artistic creation under the Ministry of Culture’s control.

Under hashtags like #TodosSomosSanIsidro (We are all San Isidro, in English) and #FreeDenis – among others regarding people detained or missing – the movement went far and beyond the Cuban borders. Artists, activists and even politicians from abroad are now supporting it, such as the deputy Alejandra Lordén, from Argentina, the Assistant Secretary of US Department of State, Michael Kozak, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who tweeted: "We urge the Cuban regime to cease harassment of San Isidro Movement protestors and to release musician Denis Solís, who was unjustly sentenced to eight months in prison. Freedom of expression is a human right.” Journalist and author Michael Deibert also recorded a video to show his support: “San Isidro Movement is not isolated. The world and all free people are looking at and supporting this fight,” he said, in Spanish.

Amnesty International says the imprisonment of Denis Solís is against international human rights laws and demanded his immediate release. It's important to note that this is not the first time that the institution interfered to release prisoners of conscience in Cuba, the only country in the Americas which prohibits Amnesty International from visiting. “These activists might be irreverent, they might be criticizing the authorities in a way that is uncomfortable for them, and they havehttps://www.fairplanet.org

Cuba’s Government Throws Its Repressive Playbook at a Journalist

Camila Acosta Endures a Year of Harassment, Arrest, and Forced Relocation

The Cuban government’s brutal restrictions on free speech fall

particularly hard on journalists. Camila Acosta has learned this from

experience. In just the one year since August 2019, when she began

working as an independent journalist for the news website CubaNet, Acosta has endured multiple instances of targeted abuse.

Earlier this summer, Acosta was waiting for friends in a park in Havana when two officers asked for her ID, arrested her, and took her to a police station. Inside her bag, they found several facemasks reading, “No to Decree 370,” an abusive 2019 law

forbidding the dissemination of information “contrary to the social

interest.” The officers forced Acosta to strip her clothes and searched

her further, she told Human Rights Watch. The police fined her and

threatened further prosecution for protesting the decree.

But this was only the most recent in a string of multiple incidents of harassment against Acosta.

In November 2019, an immigration official stopped Acosta as she was trying to board a plane for a human rights event in Argentina. He said she was forbidden to leave the country, Acosta told Human Rights Watch.

Since February, Acosta has been forced to move houses in Havana at least

six times. Each time she rented a new house, the owners soon told her

she had to leave. Some said police had chastised them for hosting a

“dissident.”

In March, police arbitrarily detained Acosta as she was covering a demonstration in Havana.

During a two-hour interrogation, one officer threatened to prosecute

her for allegedly “usurping public functions” by reporting the news.

The police eventually let her go. But two weeks later, she was summoned

back to a police station, where an officer showed her three of her

recent Facebook posts, including a meme of Fidel Castro. The officer

invoked Decree 370 and imposed a fine of 3,000 Cuban pesos (roughly

US$120), several times the average salary in Cuba.

This repeated weaponizing of Cuba’s free speech restrictions against

Acosta leads to the question: Why are authorities so afraid to let a

journalist do her job?

STATEMENT ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN CUBA

As a global organization anxious to improve international cooperation in the fields of artistic creativity, mediation and endeavour, AICA is committed to defending freedom of expression as a basic civil and human right. We therefore feel compelled to draw attention to the deteriorating relations between the government of Cuba and artists linked to the 27N activist group and San Isidro movement. Arbitrary arrests and harassment, crackdowns on protestors, and direct targeting of individuals with defamatory statements have been reliably reported. So far, the response from authorities has been to disqualify the groups as anti-Cuban agents, deflecting attention from legitimate grievances and closing the door to dialogue.

Four months ago, in November 2020, police stormed a house in the San Isidro district of Havana, purportedly to enforce health regulations, and arrested artists engaged in protesting against censorship. Though almost all were subsequently released, a steady escalation of tensions followed, culminating in a confrontation on 27 January 2021, in which Minister of Culture Alpidio Alonso reacted to protestors with a display of personal violence. Two months on from that incident, a campaign of intimidation has taken hold, with authorities citing the activists as “mercenaries”, disparaging the reputations of established artists, inciting resentment against them and even releasing their personal data – phone numbers and private audio messages – on national media outlets. Such actions generate a climate of fear and intimidation under which artists are pressured into silence. We view this as a cause for grave concern.

AICA calls on the government of Cuba to curtail individuals and agencies that act against the principle of human dignity enshrined in the ideals of the Revolution.

Regardless of their political opinions, criminalizing artists and stifling dissent are never acceptable practices under the rule of law.

On behalf of AICA International,

Lisbeth Rebollo Gonçalves, International President

Rafael Cardoso, Chair of Censorship and Freedom of Expression Committee

Download this letter on a .pdf file

In an extraordinary move, Cuban intellectuals and artists are airing their grievances publicly and collectively. Will it make a difference to freedoms in the country?

In the middle of the night on 28 November, 32 Cuban artists emerged from a five-hour meeting with officials of the Ministry of Culture. They had called on the Cuban government to refrain from harassing independent artists, to stop treating dissent as a crime, and to cease its violence against the San Isidro Movement, a group of artists and activists that had staged a hunger strike to protest the arrest and sentencing of a young rapper. The news of the encounter was shared with a crowd of about 300 artists, writers, actors and filmmakers who had stood outside for more than 12 hours to pressure ministers to open their doors. Nothing like this had ever happened before on the island.

Cubans may complain about food shortages and other restrictions on their lives, but members of elite professions rarely stick their necks out to defend anyone that the state labels a dissident. It is unheard of to exhort Cuban officials to listen to their most vocal critics in person. Although the artists of the San Isidro Movement were known to many, harassment of the group had not generated a major outcry. But in the past three years the Cuban government has issued laws imposing restrictions on independent art, music, filmmaking, and journalism, incurring the anger of many creators. When they saw live streamed videos of the weakened hunger strikers being attacked by security agents disguised as health workers, they decided that enough was enough.

“This is the first time that artists and intellectuals in Cuba are challenging the constitution,” said Cuban historian Rafael Rojas in a radio broadcast. “Their emphasis on freedom of expression and association challenges the legal, constitutional, and institutional limits of the Cuban political system.” In an interview with journalist Jorge Ramos, artist Tania Bruguera said the uprising started because, “a group of Cuban artists have gotten tired of putting up with being abused, harassed and pursued by police because of their political views and for their independence from state institutions.”

Within 48 hours, the Cuban government began to renege on verbal promises made at the meeting not to harass the protesters. President Diaz-Canel, Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez, Minister of Culture Alpidio Alonso, and Casa de las Americas director Abel Prieto all tweeted defamatory statements about the protesters. Cuban state television aired several programmes lambasting the San Isidro Movement, Tania Bruguera, and journalist Carlos Manuel Alvarez as mercenaries paid by the USA to destabilise the revolution. Bruguera and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara were threatened by state security and detained for walking outside. Police blocked off and guarded the street where the Ministry of Culture is located. Several activists and independent journalists were placed under house arrest. Police shut down the headquarters of INSTAR, Tania Bruguera’s International Institute of Artivism. The San Isidro Movement was accused on Cuban television of breaking the windows of a hard currency store, but it was soon revealed that the man who committed the act was an agent provocateur working for Cuban police.

The protests come at a moment when the Cuban government has been shaken by the colossal loss of tourism revenue during the pandemic, the dwindling support from Venezuela, and the tightening of the US trade embargo during the Trump years. It was a sign of weakness that officials ceded to the demand for a face-to-face encounter with protesters.

But the state’s reaction is not surprising. Cultural Ministry officials are expected to respond to the demands of the Communist Party and State Security, not to citizens organised outside state sanctioned organisations. The slanderous campaigns on state television and social media are intimidation tactics aimed at preventing more Cubans from rising up. And it is also not unusual for the Cuban government to clamp down on dissent during economic downturns, as happened after the failed 10-million-ton harvest in 1971 and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

What is extraordinary is that young Cuban intellectuals and artists have chosen to air their grievances publicly and collectively, and to support each other regardless of divergent political opinions. They have not been seduced by promises of favourable treatment from the state in exchange for silence, nor are they succumbing to the self-doubt that police states are so adept at inculcating in the citizenry. Most importantly, despite persistent police harassment, they are not giving up. They have adopted a name–27N–in commemoration of the day they first came together. A few members of the San Isidro Movement are part of 27N, but the group also includes representatives of other cultural fields that participated in the mass protest. 27N has formed subcommittees to attend to various tasks, from media relations to visual documentation to legal consultations.

27N continues to prepare for the next session with officials. They posted an initial list of demands in an online petition: political freedom for all Cubans, the release of the rapper Denis Solís, the cessation of state repression of artists and journalists who think differently, the cessation of defamatory media campaigns against independent artists, journalists and activists because of their political views, and the right to and respect for independence. On 27 November, Cuban officials promised a second meeting, but on 4 December the Ministry of Culture terminated the dialogue due to an “insolent” email from the protesters, who had requested to have a lawyer present and asked that harassment against them cease. Instead, the Ministry convened a meeting with small group of artists that were deemed to be loyal to the revolution. A 27N meeting at the Institute of Artivismo (INSTAR) in Havana.

The retreat may have been a result of orders from higher ranking officials as famous Cuban folk singer Silvio Rodriguez suggested. Rodriguez, considered by many to be an apologist for the regime, nonetheless understands that the officials in the cultural ministry were engaging in a defensive, though morally illegitimate, political move.

It is not surprising that prominent but independently minded Cuban artists and intellectuals such as singers Carlos Varela and Haydee Milanés have voiced support for the protesters. But it was nothing short of astonishing that the regional chapters of the Union of Cuban Artists and Writers (La Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba, UNEAC) and the Hermanos Saíz Brigade on the Island of Pines posted a message of solidarity with the San Isidro Movement on 7 December on Facebook, decrying the Cuban government’s defamatory campaigns, writing on Facebook, “We will not advance toward a dialogue and mutual respect by resorting to dismissive insults.” Cuba’s political culture does not embrace public expressions of dissent within its ranks, nor do regional representatives of organization tend to speak out about activities in the capital.

Changes in Cuban culture played a significant role in the November 27 protest. For the young Cubans who rose up in rebellion, their smartphones are weapons they use both to inform and defend themselves. The legalisation of cell phone possession in 2008 and the opening of phone-based internet access in 2018 utterly transformed Cuban public discourse. Young Cubans use Facebook as an alternative public sphere in which to share news, air grievances, galvanise support for causes and cast aspersions on their leaders. Official state media has been upstaged. Cuba’s leaders are being thrust into arguments with disgruntled citizens on social media – and their responses are undignified to say the least. The Cuban government tries to block access to opposition media, but young Cubans fight back with VPN networks and mirror sites. In her daily podcast, Yoani Sánchez explains to listeners how to use a VPN. Dozens of independent journalism publications and streaming channels have blossomed on the internet, providing Cubans with news and views that would never appear in state media.

Communication between Cuban exiles and islanders is fluid and constant, signalling a complete breakdown of the state’s effort to drive a wedge between those inside and outside the country. Cubans have grown more emboldened by being able to see what others like them do and by witnessing what the state does to other Cubans. WhatsApp chats facilitate the creation of organisations based on special interests, including Cuban doctors on medical missions who share information about the oppressive labour conditions and constant surveillance they experience. The island now has independent animal rights groups, LGBTQ groups, feminist groups and anti-racist groups, all of which have organised smaller protests in recent years using social media.

The Cuban government continues to dismiss all forms of dissent on the island as the works of mercenaries trained, financed and mobilised by the United States government as part of a long-term regime change strategy. More than a few progressives outside Cuba parrot that rhetoric or at least feel obligated to prioritise their condemnation of US policies over concerns about Cubans’ civil rights. Many Cubans and Cuban-Americans, myself included, would argue that it is a mistake to rationalise or diminish the Cuban government’s repression of civil liberties and blame the embargo for the government’s stance toward its citizens. While USAID has awarded $16,569,889 for Cuba pro-democracy efforts since 2017, including financing of some of the opposition media, not all Cuban media beyond the island government’s control was invented by the CIA, nor is all Cubans’ opposition to their government a product of American meddling. Cubans do not need the United States to “help” them develop critical views of their government. “Anger rather than fear is the widespread sentiment among Cubans—a constant, built-in discomfort,” writes Carlos Manuel Alvarez. “We’re fed up with blind, doctrinaire zeal. Navigating Communism is like trying to cross a cobblestone road in high heels, trying not to fall, feigning normalcy. Some of us end up twisting our ankles.”

Most complaints of police repression, domestic violence, animal mistreatment, food shortages and poor public services in Cuba come from ordinary Cuban citizens who post their grievances on Facebook. No American planes are dropping leaflets from the sky to provide instructions. Cuban exiles send billions of dollars to relatives and friends each year, and much of that money pays for cell phones, internet, computers and other tech equipment that allow islanders to send and receive information. Important opposition media outlets, such as 14yMedio and CiberCuba, are entirely privately financed. Tania Bruguera and Yoani Sanchez have made a point of not accepting any funding from the US government, and savvy musicians and filmmakers use crowd funding campaigns to support their projects. The bulk of US State Department funding for Cuba-related activities stays in Miami, where media companies, publishers and cultural promoters can operate freely.

Cuban citizens may have limited legal rights, but they do not lack agency; they choose to apply for foreign grants or to work for media outlets funded by American sources. I do not make these points because I favour US-backed regime change – I am arguing for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics that are leading to more frequent, more visible and more organised protests in Cuba. I am also arguing against the Cuban government’s position that does not differentiate between a CIA-financed assassin and an independent journalist who writes a brilliant essay about Cuba’s public health system, or an artist who recites poetry outside a police station.

The recent confrontation at the Ministry of Culture raised the hopes of many Cubans around the world. It also generated skepticism from those who say that dialogue with the Cuban government is futile, and that artists don’t have the knowhow to bring about political change. It’s worth recalling that the Charter 77 civic movement in former Czechoslovakia started in response to the arrest of a psychedelic rock band. The myth of Cuba as a political utopia is the revolution’s jugular: it draws tourist dollars and foreign aid, but its claim to truth is undermined by the harsh lived realities of 11 million citizens. Cuban artists and intellectuals have been enjoined to sustain that myth for 60 years. Their collective refusal to do now is a clear sign that change is on the horizon.

Coco Fusco is an artist and writer and the author of Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba (Tate Publications, 2015). She is a professor at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

This article was originally publishing in the North American Congress on Latin America here. Some minor alterations have been made to conform to Index house style

The focus of 2020 was the COVID-19 pandemic. Issues like food

insecurity, mental health, increased poverty and widespread

misinformation impacted people all over the world. As a result of

unemployment, lack of social protection and various trade restrictions

that have disrupted the international food supply chains, tens of millions of people are in danger of succumbing to extreme poverty. People’s freedom in the world is increasingly vulnerable.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health services in nearly the entire world have experienced disruption, even though the demand is increasing. The societal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered mental health conditions for some and worsened pre-existing ones for others. In a United Nations (U.N.) article addressing misinformation surrounding the pandemic, Dr. Briand, director of pandemic and epidemic diseases suggests that “when people are anxious and uncertain of a number of things they tend to compare with things they know already or things they have experienced in the past.” Fear and apprehension surrounding the vaccine have made it vital for organizations like the U.N. to provide accessible and understandable information that addresses public concerns.

Freedom in the world has been an overarching issue during the pandemic. It is also likely to have serious implications in the coming years. Freedom House is a nonpartisan, independent watchdog organization that researches and reports on various core issues within the contexts of civil liberties, political rights and democracy. Throughout 2020, Freedom House compiled reports and data on how repressive regimes have reacted to the pandemic, often at the expense of basic freedoms and public health.

Freedom House Report: “Democracy Under Lockdown”

According to a Freedom House report about the impact of COVID-19 on the global struggle for freedom, democracy and human rights has deteriorated in 80 countries since the start of COVID-19. The report is based on a survey of 398 experts from 105 countries. GQR conducted it in partnership with Freedom House. The research shows a trend of declining freedom worldwide for the past 14 years that COVID-19 has exacerbated. Countries that lack accountability in government are suffering the most due to failing institutions and the silencing of critics and opposition. Countries such as the United States, Denmark and Switzerland have also seen weakened democratic governance, even though Freedom House categorizes them as “free.” Even open societies face pressure to accept restrictions that may outlive the crisis and have a lasting effect on liberty.

5 Aspects of a Weakened Democracy During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Abuse of Power: Governments use the pandemic to justify retaining special powers, including interfering with the justice system, unprecedented restrictions on political opponents and increased surveillance. According to the research, the police violently targeted civilians in at least 59 countries. In 66 countries, detentions and arrests have increased during the pandemic response.

- Protection of Vulnerable Groups: Marginalized communities disproportionately face restrictions and discrimination and those in power often blame them for spreading the virus. Governments that abuse marginalized groups have continued to do so while international attention focuses on the pandemic. Due to government shutdowns, civil society has a reduced capacity to enforce accountability for human rights violations.

- Transparency and Anticorruption: In 37% of the 65 countries that the research included, government transparency was one of the top three issues that affected the government’s pandemic response. The report also notes that 62% of respondents said they distrust information from their national government. Some governments, such as those in Nicaragua and Turkmenistan, have outright denied the existence of the virus. Others like Brazil and Tasmania have promoted unsafe or unverified treatments. Opportunities for corruption have grown as national governments quickly distribute funds to the public without mechanisms in place to monitor those funds.

- Free Media and Expression: Freedom House research found that at least 47% of countries in the world experienced restrictions on the media as a response to the pandemic. Journalists have also been the target of violence, harassment and intimidation. At least 48% of countries have experienced government restrictions on free speech and expression. In 25% of the “free” countries, as classified by Freedom House, national governments restricted news media.

- Credible Elections: COVID-19 disrupted national elections in nine countries between January and August 2020. The postponed elections often failed to meet democratic standards because of delayed rescheduling or lack of adequate preparation for secure voting.

Protecting Freedom Now and in the Future

In 2020, the International Labor Organization (ILO) predicted that there would be a 60% decline in earnings for nearly 2 billion informal workers in the world. It is also the first year since 1998 that there will be a rise in poverty. According to Larry Diamond from Stanford University, good governance within a democracy is essential for poverty reduction. Freedom House recommends five ways to protect democracy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Emergency restrictions should be transparent with support from the rule of law while being purposeful and proportional to the threat.

- Restrictions, especially ones impacting basic rights, should not last a long time and should have independent oversight.

- Surveillance that uses new technology must be scientifically necessary and have limits on duration and scope. An independent organization should also monitor government surveillance.

- Protecting freedom of the press is important. The population should have open access to the internet and people should combat false information with clear and factual government information.

- It is essential to adjust voter registration and polling station rules, encouraging distanced voting methods and only postponing elections as a last resort.

Citizens in at least 90 countries have had significant protests against government restrictions. Journalists have risked their freedom and safety to report on the pandemic and the oppressive actions that government entities have taken. However, the pushback against reduced freedom in the world and guidelines that international organizations like Freedom House set inspire hope for a turning point in democracy’s current trajectory.

– Charlotte Severns

Photo: Flickr

Comments

Post a Comment