ISSUE 12 - MARCH 2021 - COPIES

Jill I. Goldenziel♦

ABSTRACT

Fidel Castro's government actively suppressed religion in Cuba for decades. Yet in recent years Cuba has experienced a dramatic flourishing of religious life. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cuban government has increased religious liberty by opening political space for religious belief and practice.

In 1991, the Cuban Communist Party removed atheism as a prerequisite for membership. One year later, Cuba amended its constitution to deem itself a secular state rather than an atheist state. Since that time, religious life in Cuba has grown expostially. All religious denominations, from the Catholic Church to the Afro-Cuban religious societies to the Jewish and Muslim communities, report increased participation in religious rites.

Religious social service organizations like Caritas have opened in Cuba, providing crucial socito services to Cubans of all religious faiths. These religious institutions are assisted by groups from the United States traveling legally to Cuba on religious visas and carrying vital medicine, aid, and religious paraphernalia.

What explains the Cuban government's sudden accommodation of religion?

Drawing on original field research in Havana, I argue that the Cuban government has strategically increased religionous liberty for political gain. Loopholes in U.S. sanctions policies have allowed aid to flow into Cuba from the United States via religious groups, tying Cuba's religious marketplace to its emerging economic markets.

The Cuban government has learned from the experience of similar religious awakenings in post-Communist states in Eastern Europe and has shrewdly managed the workings of religious organizations while permitting individual revival.

2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Cuba

Executive Summary

The country’s constitution, in effect since February 25, contains written provisions for religious freedom and prohibitions against discrimination based on religious grounds. According to human rights advocacy organization Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) and religious leaders, however, the Cuban Communist Party (CCP), through its Office of Religious Affairs (ORA) and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), continued to control most aspects of religious life. According to CSW, following the passage of the constitution, which was criticized by some religious groups, the government increased pressure on religious leaders, including through violence, detentions, and threats; restricting the right of prisoners to practice religion freely; and limiting or blocking international and domestic travel. Media and religious leaders said the government escalated its harassment and detention of members of religious groups advocating for greater religious and political freedom, including Ladies in White leader Berta Soler Fernandez, Christian rights activist Mitzael Diaz Paseiro, his wife and fellow activist Ariadna Lopez Roque, and Patmos Institute regional coordinator Leonardo Rodriguez Alonso. According to CSW, in July and November, authorities detained, without charges, Ricardo Fernandez Izaguirre, a member of the Apostolic Movement and journalist. Many religious groups said their inability to obtain legal registration impeded the ability of adherents to practice their religion. The ORA and MOJ continued to deny official registration to certain groups, including to several Apostolic churches, or did not respond to long-pending applications, such as those for the Jehovah’s Witnesses and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Church of Jesus Christ). According to CSW, many religious leaders practiced self-censorship because of government surveillance and infiltration of religious groups. In April media reported authorities arrested and sentenced homeschooling advocates Reverend Ramon Rigal and his wife Ayda Exposito for their refusal to send their children to government-run schools for religious reasons. In July the government prevented religious leaders from traveling to the United States to attend the Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom. According to CSW, on November 10, authorities prevented the president of the Eastern Baptist Convention from leaving the country. A coalition of evangelical Protestant churches, Apostolic churches, and the Roman Catholic Church continued to press for constitutional amendments, including easing registration of religious groups, ownership of church property, and new church construction.

The Community of Sant’Egidio, recognized by the Catholic Church as a “Church public lay association,” again held an interfaith meeting – “Bridges of Peace” – in Havana on September 22-23 to promote interreligious engagement, tolerance, and joint efforts towards peace. Approximately 800 participants from different religious groups in the country attended the meeting, which focused on the importance of peaceful interfaith coexistence.

U.S. embassy officials met briefly with Caridad Diego, the head of ORA, during a Mass in September celebrating Pope Francis’s elevation of Havana Archbishop Juan de la Caridad Garcia Rodriguez to the rank of cardinal; Diego declined to hold a follow-up meeting. Embassy officials also met regularly with a range of religious groups, including Protestants, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Muslims, and Catholics concerning the state of religious freedom and political activities related to religious groups’ beliefs. In public statements and on social media, U.S. government officials, including the President and the Secretary of State, continued to call upon the government to respect the fundamental freedoms of its citizens, including the freedom of religion. Embassy officials remained in close contact with religious groups, including facilitating meetings between visiting civil society delegations and religious groups in the country.

On December 18, in accordance with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, as amended, the Secretary of State placed Cuba on the Special Watch List for having engaged in or tolerated severe violations of religious freedom.

Section I. Religious Demography

The U.S. government estimates the total population at 11.1 million (midyear 2019 estimate). There is no independent, authoritative source on the overall size or composition of religious groups. The Catholic Church estimates 60 percent of the population identifies as Catholic. Membership in Protestant churches is estimated at 5 percent. According to some observers, Pentecostals and Baptists are likely the largest Protestant denominations. The Assemblies of God reports approximately 150,000 members; the four Baptist conventions estimate their combined membership at more than 100,000.

Jehovah’s Witnesses estimate their members at 96,000; Methodists 50,000; Seventh-day Adventists 36,000; Anglicans 22,500; Presbyterians 25,000; Episcopalians 6,000; Quakers 1,000; Moravians 750; and the Church of Jesus Christ 150 members. There are approximately 4,000 followers of 50 Apostolic churches (an unregistered loosely affiliated network of Protestant churches, also known as the Apostolic Movement) and a separate New Apostolic Church associated with the New Apostolic Church International. According to some Christian leaders, evangelical Protestant groups continue to grow in the country. The Jewish community estimates it has 1,200 members, of whom 1,000 reside in Havana. According to the local Islamic League, there are 2,000 to 3,000 Muslims, of whom an estimated 1,500 are native born. Immigrants and native-born citizens practice several different Buddhists traditions, with estimates of 6,200 followers. The largest group of Buddhists is the Japanese Soka Gakkai; its estimated membership is 1,000. Other religious groups with small numbers of adherents include Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, and Baha’is.

Many individuals, particularly those of African descent, practice religions with roots in the Congo River Basin and West Africa, including Yoruba groups, and often known collectively as Santeria. These religious practices are commonly intermingled with Catholicism, and some require Catholic baptism for full initiation, making it difficult to estimate accurately their total membership. Rastafarian adherents also have a presence on the island, although the size of the community is unknown.

Section II. Status of Government Respect for Religious Freedom

Legal Framework

According to the constitution, “the state recognizes, respects, and guarantees religious liberty” and “distinct beliefs and religions enjoy equal consideration.” The constitution prohibits discrimination based on religious beliefs. It declares the country is a secular state and provides for the separation of religious institutions and the state.

The constitution also “recognizes, respects, and guarantees people’s freedom of thought, conscience, and expression.” It states, “Conscientious objection may not be invoked with the intention of evading compliance with the law or impeding another from the exercise of their rights.” It also provides for the “right to profess or not profess their religious beliefs, to change them, and to practice the religion of their choice…”, but only “with the required respect to other beliefs and in accordance with the law.”

The government is subordinate to the Communist Party; the party’s organ, the ORA, enlists the MOJ and the security services to control religious practice in the country. The ORA regulates religious institutions and the practice of religion. The Law of Associations requires all religious groups to apply to the MOJ for official registration. The MOJ registers religious denominations as associations on a basis similar to how it officially registers civil society organizations. The application process requires religious groups to identify the location of their activities, their proposed leadership, and their funding sources, among other requirements. Ineligibilities for registration may include determinations by the MOJ that another group has identical or similar objectives, or the group’s activities “could harm the common good.” Even if the MOJ grants official registration, the religious group must request permission from the ORA each time it wants to conduct activities other than regular services, such as holding meetings in approved locations, publishing major decisions from meetings, receiving foreign visitors, importing religious literature, purchasing and operating motor vehicles, and constructing, repairing, or purchasing places of worship. Groups failing to register face penalties ranging from fines to closure of their organizations and confiscation of their property.

The penal code states membership in or association with an unregistered group is a crime; penalties range from fines to three months’ imprisonment, and leaders of such groups may be sentenced to up to one year in prison.

The law regulates the registration of “house churches” (private residences used as places of worship). Two house churches of the same denomination may not exist within two kilometers (1.2 miles) of one another and detailed information – including the number of worshippers, dates and times of services, and the names and ages of all inhabitants of the house in which services are held – must be provided to authorities. The law states if authorization is granted, authorities will supervise the operation of meetings; they may suspend meetings in the house for a year or more if they find the requirements are not fulfilled. If an individual registers a complaint against a church, the house church may be closed permanently and members may be subject to imprisonment. Foreigners must obtain permission before attending services in a house church; foreigners may not attend house churches in some regions. Any violation will result in fines and closure of the house church.

The constitution states, “The rights of assembly, demonstration and association are exercised by workers, both manual and intellectual; peasants; women; students; and other sectors of the working people,” but it does not explicitly address religious association. The constitution prohibits discrimination based on religion.

Military service is mandatory for all men, and there are no legal provisions exempting conscientious objectors from service.

Religious education is highly regulated, and homeschooling is illegal.

The country signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 2008 but did not ratify it. The government notes, “With respect to the scope and implementation of some of the provisions of this international instrument, Cuba will make such reservations or interpretative declarations as it may deem appropriate.”

Government Practices

Many religious groups said notwithstanding constitutional provisions providing for freedom of conscience and religion and prohibiting discrimination based on religion, the government continued to use threats, detentions, violence, and other coercive tactics to restrict certain religious groups, and leaders’ and followers’ activities, including the right of prisoners to practice religion freely, and applied the law in an arbitrary and capricious manner. Religious leaders said before and following implementation of the new constitution on February 25, the government increased its pressure on religious leaders, while curtailing freedom of religion and conscience.

According to CSW, reports of authorities’ harassment of religious leaders increased in parallel with churches’ outspokenness regarding the constitution. CSW reported that, before the passage of the constitutional referendum in February, officials told religious leaders they would be charged as “mercenaries and counterrevolutionaries” if they did not vote for the new constitution. According to CSW, on February 12, CCP officials summoned Christian, Yoruba, and Masonic leaders in Santiago, to “confirm” they and their congregations would vote to adopt the new constitution. According to online media outlet CiberCuba, on February 22, security agents from the Technical Department of Investigation (Departamento Tecnico de Investigaciones, or DTI) arrested Roberto Veliz Torres, a minister of the Assembly of God in Palma Soriano, allegedly for pressuring his congregants to vote “no” in the constitutional referendum. Several other pastors, mostly Protestants, were arrested, threatened by state security officials, and attacked in official media for the same motive, such as Pastor Carlos Sebastian Hernandez Armas of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Havana’s Cotorro neighborhood. In a February 23 article in a state newspaper, Herndandez Armas was attacked by name as a “counterrevolutionary” for refusing to support the new constitution. According to media outlet 14yMedio.com, an official from the ORA named Sonia Garcia Garcia telephoned Dariel Llanes, head of the Western Baptist Convention, of which Hernandez Armas’ church is a member, to inform him that the pastor would “no longer be treated like a pastor, but instead like a counterrevolutionary.” One church leader stated government officials sought to intimidate religious leaders because the officials thought some religious leaders were openly promoting a “no” vote on the constitution. Some religious groups stated concerns the new constitution significantly weakened protections for freedom of religion or belief, as well as diluting references to freedom of conscience and separating it from freedom of religion.

According to the U.S-based Patmos Institute, police summoned and interrogated Yoruba priest Loreto Hernandez Garcia, vice president of the Free Yorubas of Cuba, which was founded in 2012 by Yorubas who disagreed with the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba, which they allege is controlled by the ORA. According to the U.S. based Global Liberty Alliance, authorities accused the Free Yorubas of “destabilizing society,” and subjecting their leaders to arbitrary detentions and beatings, destruction of ceremonial objects, police monitoring, and searches-and-seizures without probable cause.

According to media, prison authorities continued to abuse Christian rights activist Mitzael Diaz Paseiro for his refusal to participate in ideological re-education programs while incarcerated. Diaz Paseiro, imprisoned since November 2017 and recognized by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience, was beaten, prohibited from receiving visits or phone calls, denied medical and religious care, and confined to a “punishment” cell. Diaz Paseiro was serving a three year and five-month sentence for “pre-criminal dangerousness” for protesting municipal elections in 2017.

Media reported that police continued their repeated physical assaults against members of the Ladies in White, a rights advocacy organization, on their way to Mass. Reports indicated the group’s members typically attempted to attend Mass and then gathered to protest the government’s human rights abuses. Throughout the year, Soler Fernandez reported repeated arrests and short detentions for Ladies in White members when they attempted to meet on Sundays. According to media, because of the government’s intensified pressure on the movement, the women were placed under brief house arrest on Sundays in order to prevent them from attending Mass. Soler Fernandez said she was arrested every Sunday she tried to exit her house to protest. She and other Ladies in White members were frequently physically abused while in police custody, as shown by videos of their arrests. After being taken into custody, they were typically fined and released shortly thereafter.

According to media, authorities specifically harassed and threatened journalists reporting specifically on abuses of religious freedom. On April 22, police arrested and assaulted journalist and lawyer Roberto Quinones while he was reporting on a trial involving religious expression. Officers approached and arrested Quinones while he was interviewing a daughter of two Protestant pastors facing charges because they wanted to homeschool their children because of hostility and bullying their children were subject to in state schools due to their faith. When Quinones asked why he was being arrested, an officer pulled Quinones’ hands behind his back, handcuffed him, and threw him to the ground. The officers then dragged him to their police car. One of the arresting officers struck Quinones several times, including once on the side of the head with enough force to rupture his eardrum. On August 7, a court sentenced him to one year of “correctional labor” for “resistance and disobedience”; he was imprisoned on September 11 after authorities denied his appeal. Quinones continued to write while in prison, especially about the bleak conditions of the facility, although he wrote a letter stating he was happy to “be here for having put my dignity before blackmail.” When the letter was published on CubaNet, an independent domestic online outlet, prison authorities reportedly punished Quinones and threatened him with disciplinary action. Patmos reported that on August 9, Yoel Suarez Fernandez was detained and threatened for reporting on the Rigal and Quinones cases, and authorities confiscated his phone.

According to media, in April authorities arrested homeschooling advocates Reverend Ramon Rigal and his wife Ayda Exposito. The couple said they objected to the atheistic ideological instruction integral to the Communist Party curriculum of state schools and the abuse their children were subjected to for their parents’ beliefs, including the bullying of their daughter at school because she was Christian. The couple withdrew their children from the state school and enrolled them in an online program based in Guatemala. The reports stated the family, who belong to the Church of God in Cuba, were given 30 minutes’ notice before their trial began on April 18. At trial, the prosecutor stated education at home was “not permitted in Cuba because it has a capitalist foundation” and only government teachers are prepared to “instill socialist values.” In addition to a fine for truancy, Rigal was sentenced to two years in prison and Exposito 18 months for refusing to send their children to the government school, as well as for “illicit association” for leading an unregistered church. In December, Diario de Cuba reported state judicial officials denied Ayda parole. Another couple in their church was also sentenced to prison for refusing to send their children to state schools.

According to CSW, on July 12, state security agents detained Ricardo Fernandez Izaguirre after he left the Havana headquarters of the Ladies in White where he had been documenting human rights abuses. A member of the Apostolic Movement and a journalist, Fernandez was released on July 19 and reportedly never charged. According to CSW, on November 13, authorities summoned Fernandez and his wife Yusleysi Gil Mauricio to the Camaguey police station. After separating the couple, security agents reportedly told her that Fernandez “would be judged for being a counterrevolutionary.” Fernandez was released November 19 after four days of detention, again without charge. Fernandez said he believed the detentions were because of his reporting on authorities’ religious freedom abuses.

Patmos reported that on October 31, authorities detained, interrogated, and threatened Velmis Adriana Marino Gonzalez for two hours for leading a female Apostolic movement. Another member of the Apostolic Movement and leader of the Emanuel Church in Santiago de Cuba, Alain Toledano Valiente, reported to CSW that police had summoned him three times during the year. He said authorities opposed the construction of a new church (authorities demolished the previous Emanuel Church and detained hundreds of church members in 2016), even though he had the permits to build the new church. Following one summons, Toledano stated, “In Cuba pastors are more at risk than criminals and bandits… I cannot carry out any religious activity; that is to say they want me to stop being a pastor.”

Patmos reported during the year authorities repeatedly pressured and threatened 17-year-old Yoruba follower Dairon Hernandez Perez for his refusal to enlist in the military due to his religious beliefs.

According to CSW, many religious groups continued to state their lack of legal registration impeded their ability to practice their religion. Several religious groups, including the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Church of Jesus Christ, continued to await a decision from the MOJ on pending applications for official registration, some dating as far back as 1994. On October 23, Ambassador to the United States Jose Cabanas met with the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ in Salt Lake City and told church leaders the denomination was “welcome” in Cuba; however, the ORA did not approve the Church’s registration by year’s end.

Representatives of several religious organizations that had unsuccessfully sought registration said the government continued to interpret the law on associations as a means for the ORA and the MOJ to deny registration of certain groups. In some cases, the MOJ delayed requests for registration or cited changing laws to justify a lack of approval. EchoCuba, a U.S.-based international religious freedom advocacy group, reported that some Apostolic churches repeatedly had their attempts to register denied, forcing them to operate without legal status. According to Patmos, in June seven registered groups formed the Alliance of Evangelical Churches (AIEC), but the ORA denied their registration.

Members of Protestant denominations said some groups were still able to register only a small percentage of house churches in private homes, although some unregistered house churches could operate with little or no government interference. According to EchoCuba, however, several religious leaders, particularly those from smaller, independent house churches or Santeria communities, said the government was less tolerant of groups that relied on informal locations, including private residences and other private meeting spaces, to practice their beliefs. They said the government monitored them, and, at times, prevented them from holding religious meetings in their spaces. CSW reported authorities continued to rely on two 2005 government resolutions to impose complicated and repressive restrictions on house churches.

According to EchoCuba, the ORA approved some registration applications, but it took up to two to three years from the date of the application to complete the process. Soka Gakkai was the only Buddhist group registered with the government.

According to religious leaders and former prisoners, authorities continued to deny prisoners, including political prisoners, pastoral visits and the ability to meet with other prisoners for worship, prayer, and study. Many prisoners also said authorities repeatedly confiscated Bibles and other religious literature, sometimes as punishment and other times for no apparent reason.

According to media, in August the ORA informed Catholic leaders that it had cancelled the annual Catholic public youth day celebrations, except in the city of Santiago. The announcement came after police prevented some Catholic priests, journalists, and others from attending the funeral of Cardinal Jaime Ortega at the Havana cathedral on July 28.

According to CSW, the government, through the Ministry of Interior, systematically planted informants in all religious organizations, sometimes by persuading or intimidating members and leaders to act as informants. The objective was to monitor and intimidate religious leaders and report on the content of sermons and on church attendees. As a result, CSW assessed, many leaders practiced self-censorship, avoiding stating anything that might possibly be construed as anti-Castro or counterrevolutionary in their sermons and teaching. Catholic and Protestant Church leaders, both in and outside of the Council of Cuban Churches (CCC), reported frequent visits from state security agents and CCP officials for the purpose of intimidating them and reminding them they were under close surveillance, as well as to influence internal decisions and structures within the groups. In October state security officials reportedly summoned and interrogated a Protestant leader and a Catholic leader, warning both to leave their churches for their “counterrevolutionary” activities and threatening them with imprisonment if they did not comply. Many house church leaders continued to report frequent visits from state security agents or CCP officials. Some reported warnings from the agents and officials that the education of their children, or their own employment, could be “threatened” if the house church leaders continued with their activities. In March an officer informed Yoel Ruiz Solis in Pinar del Rio that he was operating an illegal church in his home and threatened to confiscate his house and open criminal proceedings against him. In August and October officials from the Ministry of Physical Planning accused Rudisvel Ribeira Robert of various violations; during the second visit they threatened him with a fine if he continued to allow religious activities on his property.

Many house church leaders continued to report frequent visits from state security agents or CCP officials. Some reported warnings from the agents and officials that the education of their children, or their own employment, could be “threatened” if the house church leaders continued with their activities. In March an officer informed Yoel Ruiz Solis in Pinar del Rio that he was operating an illegal church in his home and threatened to confiscate his house and open criminal proceedings against him. In August and October officials from the Ministry of Physical Planning accused Rudisvel Ribeira Robert of various violations; during the second visit they threatened him with a fine if he continued to allow religious activities on his property.

According to Patmos, the Rastafarians, whose spiritual leader remained imprisoned since 2012, were among the most stigmatized and repressed religious groups. The Patmos report said reggae music, the primary form of Rastafarian expression, was marginalized and its bands censored. According to Sandor Perez Pita, known in the Rastafarian world as Rassandino, reggae was not allowed on most state radio stations and concert venues, and Rastafarians were consistently targeted in government crackdowns on drugs, incarcerating them for their supposed association with drugs without presenting evidence of actual drug possession or trafficking. Authorities also subjected Rastafarians to discrimination for their clothing and hairstyles, including through segregation of Rastafarian schoolchildren and employment discrimination against Rastafarian adults.

According CSW, Christian leaders from all denominations said there was a scarcity of Bibles and other religious literature, primarily in rural areas. Some religious leaders continued to report government obstacles preventing them from importing religious materials and donated goods, including bureaucratic obstructions and arbitrary restrictions such as inconsistent rules on computers and electronic devices. In some cases, the government held up religious materials or blocked them altogether. Patmos reported one pastor witnessed authorities at the airport confiscate 300 Bibles U.S. tourists attempted to bring in with them. According to Patmos, the Cuban Association for the Divulgation of Islam was unable to obtain a container of religious literature embargoed since 2014. Several other groups, however, said they continued to import large quantities of Bibles, books, clothing, and other donated goods.

The Catholic Church and several Protestant representatives said they continued to maintain small libraries, print periodicals and other information, and operate their own websites with little or no formal censorship. The Catholic Church continued to publish periodicals and hold regular forums at the Varela Center that sometimes criticized official social and economic policies.

By year’s end, the government again did not grant the Conference of Catholic Bishops’ (CCB) public requests to allow the Catholic Church to reopen religious schools and have open access to broadcasting on television and radio. The ORA continued to permit the CCB to host a monthly 20-minute radio broadcast, which allowed the council’s messages to be heard throughout the country. No other churches had access to mass media, which remained entirely state-owned. Several religious leaders continued to express concern about the government’s restriction on broadcasting religious services over the radio or on television.

According to media, the government continued to prohibit the construction of new church buildings. All requests, including for minor building repairs, needed to be approved by the ORA, which awarded permits according to the inviting association’s perceived level of support for or cooperation with the government. For example, despite spending thousands of dollars in fees and finally receiving ORA approval in 2017, in April the ORA rescinded permission for renovations to the Baptist Church in Holguin after church leaders participated in a campaign to abstain from nationwide voting on the new constitution. Berean Baptist Church, whose request for registration was pending since 1997, could not repair existing church buildings because as an unregistered group it could not request the necessary permits.

According to CSW, “The use of government bureaucracies and endless requirements for permits that can be arbitrarily cancelled at any time is typical of the way the Cuban government seeks to control and restrict freedom of religion or belief on the island. The leaderships of the Maranatha Baptist Church and the Eastern Baptist Convention have done everything right and have complied with every government requirement. In return, the Office of Religious Affairs has once again acted in bad faith and subjected them to a Kafkaesque ordeal, where they find themselves right where they started over two years ago.” Reportedly, the ORA’s processes meant many communities had no legal place to meet for church services, particularly in rural areas. Other denominations, especially Protestants, reported similar problems with the government prohibiting them from expanding their places of worship by threatening to dismantle or expropriate churches because they were holding “illegal” services.

According to CSW, several cases of authorities’ arbitrary confiscation of church property remained unresolved – including land owned by the Western Baptist Convention the government confiscated illegally in 2012 and later transferred to two government companies. Many believed the act was in retaliation for the refusal of the Western Baptist Convention to agree to various ORA demands to restructure its internal governance and expel a number of pastors. One denomination reported the Ministry of Housing would not produce the deeds to its buildings, required to proceed with the process of reclaiming property. The ministry stated the deeds had been lost. The Methodist Church of Cuba said it continued to struggle to reclaim properties confiscated by the government, including a theater adjacent to the Methodist church in Marianao, Havana. The Methodist Church reportedly submitted all necessary ownership documentation; government officials told them the Church’s case was valid but took no action during the year. According to CSW, In March officials threatened to confiscate a church belonging to a registered denomination in Artemisa. On April 17, during the week before Easter, officials notified the Nazarene Church of Manzanillo that they intended to expropriate the church building used by the congregation for 20 years. The government took no further action regarding the Manzanillo church through the end of the year.

According to media, religious discrimination against students was a common practice in state schools, with multiple reports of teachers and Communist Party officials encouraging and participating in bullying. In November Olaine Tejada told media authorities were pressuring him to retract his earlier allegations that his 12-year-old son, Leosdan Martinez, had been threatened with expulsion from a secondary school in Nuevitas Camaguey in 2018 because they were Jewish. On December 3, media reported schoolmates took off his kippah and beat him in the face with a pistol. According to CSW, on December 11, education authorities forbade sons from entering the school if they wore the kippah. The Nuevitas municipal director of education imposed the kippah ban after a government commission found a school guard guilty of failing to protect the older of the two boys, who had been beaten by fellow students on a regular basis for several months. Rather than sanctioning the guard, they instituted a kippah ban. Authorities threatened to open legal proceedings against the parents for refusing to send the children to school.

According to religious leaders, the government continued to selectively prevent some religious groups from establishing accredited schools but did not interfere with the efforts of some religious groups to operate seminaries, interfaith training centers, before- and after-school programs, eldercare programs, weekend retreats, workshops for primary and secondary students, and higher education programs. The Catholic Church continued to offer coursework, including entrepreneurial training leading to a bachelor’s and master’s degree through foreign partners. Several Protestant communities continued to offer bachelor’s or master’s degrees in theology, the humanities, and related subjects via distance learning; however, the government did not recognize these degrees.

Jehovah’s Witnesses leaders continued to state they found the requirements for university admission and the course of study incompatible with the group’s beliefs since their religion prohibited them from political involvement.

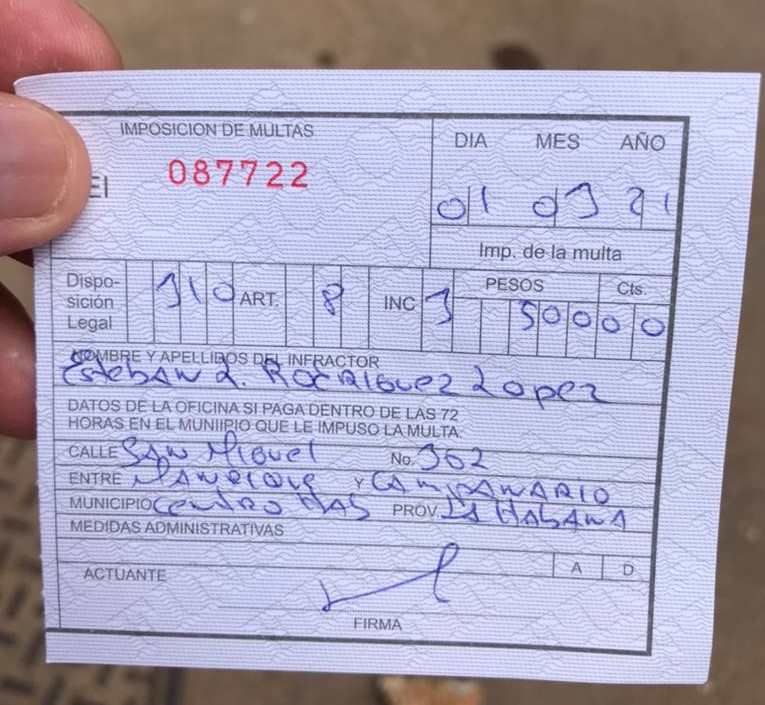

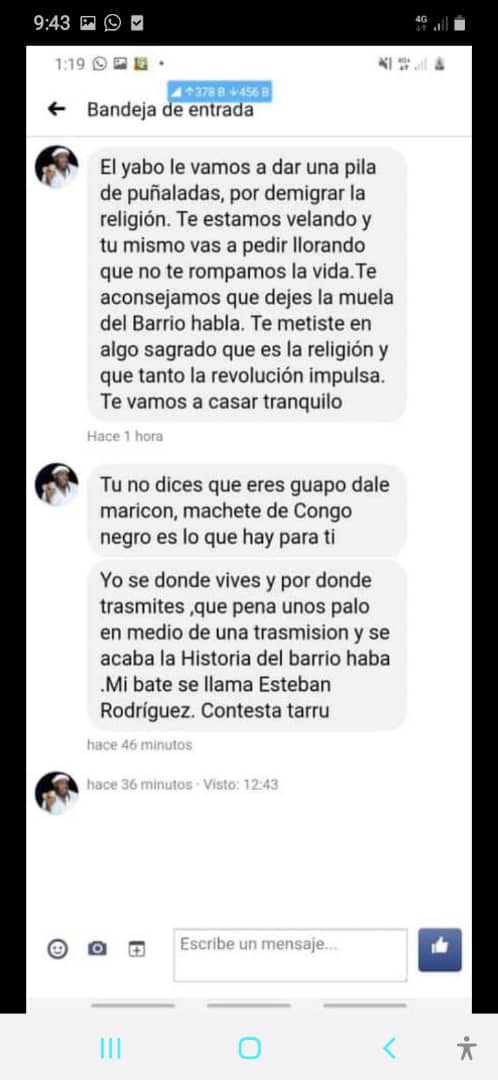

CSW reported a new development in the government’s use of social media to harass and defame religious leaders. In some cases, posts were made on the Facebook accounts of public figures targeting religious leaders or groups. In most instances, the accounts posting attacks targeting religious leaders seemed to be linked to state security. In the run-up to the constitutional referendum, Pastor Sandy Cancino, who had been publicly critical of the draft constitution, was criticized on social media and accused of being a “religious fundamentalist paid by the imperialists.”

According to CSW, on October 18, a Catholic lay leader running a civil society organization with a Christian ethos was stopped on his way to Havana, where he planned to visit a priest for religious reasons. His taxi was stopped in what first appeared to be a routine police check, but a state security agent came to the checkpoint, interrogated him for an hour and a half, and threatened him with prison if he continued to work for this organization.

According to Patmos, immigration officers continued to target religious travelers and their goods and informed airport-based intelligence services of incoming and outgoing travel. Patmos reported that in May Muslim activists from the Cuban Association for the Divulgation of Islam traveled to Pakistan to attend a training session. Throughout their stay in Pakistan, Cuban security officials sent threatening messages through their relatives in Cuba, warning them they would be arrested if they returned. Reportedly, the activists returned home despite the threats.

The government continued to block some religious leaders and activists from traveling, including preventing several religious leaders from traveling to the United States to attend the Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom at the Department of State in July and other religious gatherings outside of Cuba. The Patmos Institute’s annual report listed 24 individuals who were banned from traveling due to their religious affiliation. CSW reported that a pastor from the Western Baptist Convention was prohibited from traveling to the United States in September to attend a spiritual retreat. According to CSW, on November 10, the president of the Eastern Baptist Convention, one of the largest Protestant denominations on the island and one of the founding members of the Cuban Evangelical Alliance, was stopped from boarding a flight and informed that he was banned from leaving the country.

According to 21Wilberforce, a U.S.-based Christian human rights organization, in November the government prevented several church leaders affiliated with the AIEC from leaving the island to attend the AIEC’s general assembly in Indonesia. One pastor said that in addition to harassment, intimidation and interrogations, authorities prevented the AIEC from receiving visits from overseas pastors and church leaders by denying them the necessary visitor visas.

According to Patmos, the government denied a considerable number of religious visas, including to a group of missionaries from Florida that had visited annually to rebuild temples. On September 13, immigration officials interrupted an Apostolic conference in Mayabeque Province and threatened foreign visitors with deportation for participating in an “illegal conference.” Also, according to Patmos, pastors on tourist visas reported constant and obvious monitoring by security officials and occasional interrogations and threats.

According to EchoCuba, the government continued to give preference to some religious groups and discriminated against others. EchoCuba reported the government continued to apply its system of rewarding churches obedient and sympathetic to “revolutionary values and ideals” and penalizing those that were not. Similarly, the government continued to reward cooperative religious leaders and threatened revocation of rights for noncooperative leaders. According to EchoCuba, in exchange for their cooperation, CCC members continued to receive benefits other nonmember churches did not always receive, including building permits, international donations of clothing and medicine, and exit visas for pastors to travel abroad. EchoCuba said individual churches and denominations or religious groups also experienced different levels of consideration by the government depending on the leadership of those groups and their relationship with the government. Of the 252 violations of freedom of religion or belief reported to CSW during the year, only 5 percent involved members of CCC religious groups.

Reportedly because of internal restrictions on movement, government agencies regularly refused to recognize a change in residence for pastors and other church leaders assigned to a new church or parish. These restrictions made it difficult or impossible for pastors relocating to a different ministry to obtain government services, including housing. Legal restrictions on travel within the country also limited itinerant ministry, a central component of some religious groups. According to EchoCuba, the application of the decree to religious groups was likely part of the general pattern of government efforts to control their activities. Some religious leaders said the decree was also used to block church leaders from traveling within the country to attend special events or meetings. Church leaders associated with the Apostolic churches regularly reported they were prevented, sometimes through short-term detention, from traveling to attend church events or carry out ministry work.

Some religious leaders said the government continued to restrict their ability to receive donations from overseas, citing a measure prohibiting churches and religious groups from using individuals’ bank accounts for their organizations and requiring individual accounts to be consolidated into one per denomination or organization. Reportedly, it continued to be easier for larger, more organized churches to receive large donations, while smaller, less formal churches continued to face difficulties with banking procedures.

Some religious groups continued to report the government allowed them to engage in community service programs and to share their religious beliefs. International faith-based charitable operations such as Caritas, Sant’Egidio, and the Salvation Army maintained local offices in Havana. Caritas continued to gather and distribute relief items, providing humanitarian assistance to all individuals regardless of religious belief.

Some religious groups again reported an increase in the ability of their members to conduct charitable and educational projects, such as operating before- and after-school and community service programs, assisting with care of the elderly, and maintaining small libraries of religious materials. They attributed the increase in access to the government’s declining resources to provide social services. Religious leaders, however, also reported increased difficulties in providing pastoral services.

Media reported that during the year, the government-run historian office in Havana helped restore the Jewish cemetery, the oldest in the country, as part of its celebration of the 500th anniversary of the founding of the city.

On January 26, the first new Catholic church since the revolution, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, was opened in Sandino, near the town of Pinar del Rio. This church was the first of three Catholic churches for which the government issued building permits.

Section III. Status of Societal Respect for Religious Freedom

The Community of Sant’Egidio, recognized by the Catholic Church as a “Church public lay association,” again held an 800-person interfaith meeting – “Bridges of Peace” – in Havana on September 22-23 to promote interreligious engagement, tolerance, and joint efforts towards peace.

Section IV. U.S. Government Policy and Engagement

Embassy officials had a brief encounter with Caridad Diego, the head of ORA, during a Mass in September celebrating the Vatican’s appointment of Cardinal Garcia Rodriguez; Diego declined to hold a requested follow-up meeting. In public statements and through social media postings, U.S. government officials, including the President and Secretary of State, continued to call upon the government to respect its citizens’ fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of religion and expression.

Embassy officials met with the head of the CCC and discussed concerns unregistered churches faced to gain official status.

Embassy officials continued to meet with a range of registered and unregistered religious groups, including Protestants, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Muslims, and Catholics, to discuss the principal issues of religious freedom and tolerance affecting each group, including freedom of assembly, church expansion, access to state-owned media, and their inability to open private religious schools.

Embassy engagement included facilitating exchanges among visiting religious delegations and religious groups, including among visiting representatives of U.S. religious organizations. The groups often discussed the challenges of daily life in the country, including obtaining government permission for certain activities, and difficulty for local and U.S. churches to maintain connections in the face of increasing travel restrictions imposed by the government that prevented religious leaders from leaving the country, and increased refusal rates of visas for U.S. travelers to Cuba for religious purposes.

On December 18, in accordance with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, as amended, the Secretary of State placed the country on the Special Watch List for having engaged in or tolerated severe violations of religious freedom.

X. LIMITS ON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

The Church calls all to bring their faith to life... in order to achieve true liberty, which includes the recognition of human rights and social justice.Pope John Paul II, Homily in Santiago, Cuba, January 24, 1998

...The Cuban people cannot be deprived of links to other peoples that are necessary for their economic, social, and cultural development, especially when the isolation provokes indiscriminate repercussions in the population, exaggerating the difficulties of the most weak in basic respects, as with food, health, and education. Everyone can and should take concrete steps for a change in this respect.

Pope John Paul II, Farewell Address at the José Martí International Airport, Havana, January 25, 1998

Pope John Paul II's January 1998 visit to Cuba sparked hope that the government would ease its repressive tactics and would allow greater religious freedom. The papal visit provided unprecedented opportunities for public demonstrations of faith in a country that imposed tight restrictions on religious expression in 1960 and was officially atheist until 1992. Although Cuba refused visas to some foreign journalists and pressured some domestic critics, the pope's calls for freedom of religion, conscience, and expression created an unprecedented air of openness. But while Cuba permits greater opportunities for religious expression than it did in past years, and has allowed several religious-run humanitarian groups to operate, the government still maintains tight control on religious institutions, affiliated groups, and individual believers. Since the exercise of religious freedom is closely linked to other freedoms, including those of expression, association, and assembly, Cuban believers face multiple restrictions on religious expression.

Cuba's reluctance to lift additional bars on religious expression likely stems from the status of Cuban churches as among the country's few nongovernmental institutions with national scope. The Catholic church, which claims as adherents some 70 percent of Cuba's population—although only a small portion of these are practicing Catholocism—stands as the largest, best organized, national,nongovernmental institution.77 Practicioners of Afro-Cuban faiths, including Santería and La Regla de Ocha, are believed to be second to Catholics in numbers, while Protestant churches, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Jews comprise smaller denominations.78 Despite substantial impediments to religious expression, which are detailed below, Cuba's faithful have made progress in recent years. For example, Cuba apparently has improved its treatment of the nation's approximately 80,000 Jehovah's Witnesses, who previously encountered government harassment due to their religious opposition to military service and participation in pro-government organizations. At a December 1998 international conference of Jehovah's Witnesses in Havana, a member of the religion's governing board praised the Cuban government, saying that it "clearly sees that Jehovah's Witnesses form an integral part of the society in which we live."79 Believers from distinct faiths are holding services, forming community groups, in some cases producing publications—albeit with limited distribution—and offering significant humanitarian assistance to the population.80

Yet, Cuba apparently keeps religious groups,

particularly the Catholic church, under surveillance. One former Interior

Ministry official who reportedly was responsible for questions of national

security told the Miami Herald, that "The church was always seen

as a danger because it is the only force inside the country capable of

bringing people together and even organizing a subtle form of

resistance." This official and two other

high-ranking former Cuban governmentofficials said that Cuba assigned between

ten and fifteen intelligence officials to spy on religious institutions.81

Cuban law claims to ensure religious freedom, and has allowed for broader religious expression in recent years, yet simultaneously restricts it. In 1992, reforms to the 1976 constitution decreed that Cuba was no longer an atheistic state and that religious freedoms would be guaranteed if they were "based on respect for the law."82 But Cuba's constitution and other laws create impediments to the freedoms of association, expression, and assembly, all essential aspects of religious expression. Cuba's Criminal Code penalizes "abuse of the freedom of religion," which is broadly defined as invoking a religious basis to oppose educational objectives or the failure to take up arms in the country's defense or to show reverence for the homeland's symbols.83 While Human Rights Watch does not know of any recent prosecutions for this crime, Cuba's failure to rescind it calls into question the government's commitment to protecting religious rights.

Cuba grants the Department of Attention to Religious Affairs of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Departamento de Atención a los Asuntos Religiosos del Comité Central del Partido Comunista) a prominent role in overseeing religious institutions. Not surprisingly, religious leaders who support the government face fewer impediments to their activities than do believers who find themselves at odds with the ruling party. At the 1991 Communist Party Fourth Congress, the party decided that religious belief would no longer pose an obstacleto membership.84 In the wake of this decision, some religious figures are now members of the Communist Party or even political leaders themselves, such as Pablo Odén Marichal, the president of the Cuban Council of Churches (Consejo Cubano de Iglesias), who is a deputy in Cuba's National Assembly. Baptist Minister Raúl Suárez Ramos, with the Cuban Council of Churches, also is a deputy in Cuba's National Assembly, and heads the Martin Luther King Memorial Center, a nongovernmental group with close ties to the government.85 Suárez Ramos earned government acclaim in 1990 when he lauded the revolution as "a blessing for our poor people" and criticized U.S. policy toward Cuba as an "economic, political, radio, and television aggression."86 Both deputies often travel internationally and participate in conferences on religion in Cuba. But the party treats distinctly those who do not share its political views. The current head of the party's religious affairs office, Caridad Diego, criticized an American Catholic priest who had worked in the Villa Clara area for supporting "counterrevolutionary groups."87 The priest, Patrick Sullivan, had posted copies of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights in his church and had urged his parishioners to defend those rights. In April 1998, facing increasing government pressure, Sullivan chose to leave Cuba. Although Cuba and the Vatican had agreed that the pope would visit Cuba in 1989, the Catholic church's failure to condemn the U.S. embargo at that time apparently contributed to the several-year delay in finalizing the visit.88 When the pope did travel to Cuba in early 1998, the Cuban government trumpeted his criticisms of the U.S. embargo.

Pope John Paul II's Visit to Cuba

On a positive note, the government allowed massive public demonstrations of faith during the pope's January 1998 visit to Cuba. The pope presided over four open-air Catholic masses, in Santa Clara, Camagüey, Santiago, and Havana. Tens of thousands of Cubans attended, hearing the pope's exhortations for freedom of religion and conscience, which also were broadcast on Cuban state-controlled television. In a remarkable visual display, Cuban authorities allowed a huge mural of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to rise in the Plaza of the Revolution, where it stood for the papal mass between statues of Cuban heroes Ernesto "Ché" Guevara and José Martí. The government not only allowed citizens to attend papal masses, but encouraged them to do so, calling on the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution and other mass organizations to turn out as well. However, government agents reportedly notified some dissidents that they should not attend the papal events. At the papal mass in Havana, some government supporters reportedly attempted to drown out the cries of "liberty" from the crowd. Two men and one woman who criticized the government reportedly were arrested at the same mass, one by state security agents and the other by men wearing Cuban Red Cross uniforms.89 Cuba also had failed to grant dozens of foreign reporters and some international human rights activists permission to travel to Cuba for the papal pilgrimage.90

In his speeches and homilies, Pope John Paul II urged respect for human rights and called for the unconditional release of political prisoners. At the mass in Havana, the pope stated that liberation "finds its fullness in the exercise of the freedom of conscience, the base and foundation of the other human rights."91 Of the Cuban clergy, Archbishop Pedro Meurice of Santiago received public acclaim when his welcoming remarks for the Santiago papal mass included the statement that, "our people are respectful of authority, and want order, but they need to learn to demystify false messiahs."92 Following the papal visit, Cuba released some one hundred political prisoners, but most of these had served the majority of theirsentences, and police required them to agree to refrain from opposition activities. Cuba freed seventeen of these prisoners on the condition that they accept exile in Canada, violating their right to remain in their homeland and setting aside the pope's request for the reintegration of prisoners into Cuban society.93

Restrictions of Religious Expression

The Central Committee of the Communist Party's Department of Attention to Religious Affairs reportedly reviews religious institutions' requests to build churches, hold marches, print materials and obtain printing presses, import vehicles or other supplies, receive and deliver humanitarian aid, obtain entry or exit visas for religious workers or operate religious schools. Cuba's heavy-handed measures against religious institutions on these matters impede religious freedom. For example, the department's director, Caridad Diego, stated that her office had no intention of approving religious schools. Diego gave a vague response when asked about 130 pending visa applications for foreign clergy, saying only that they were "not a closed issue."94 Since Cuba expelled most foreign priests and nuns shortly after the revolution, there are now some 900 Catholic clergy in Cuba, half of them Cuban. Cuba had approved some twenty entry visas for foreign clergy shortly before the papal visit. As of December 1998, Cuba had approved entry visas for forty additional foreign Catholic priests and nuns.95 Cuba pressures Cuban religious workers by denying them exit visas. The government reportedly denied a Baptist pastor, Rev. Roberto Hernández Aguiar, permission to travel outside Cuba in September 1998.96 Churches hoping to expand operations in Cuba also are slowed by the government's refusal to permit church construction and a ban onservices held outside of churches, in "house churches."97 From the revolution until 1990, Cuba reportedly only allowed the construction of one church, a Protestant one in Varadero. In 1997 and early 1998, Cuba granted the Catholic church permission to build one seminary and one church.98

In June 1998 the Communist Party reportedly refused permits for religious processions in Arroyo Naranjo to celebrate the feast day of Saint Anthony, and in Calabazar, in the municipality of Boyeros, to celebrate the feast of Saint John the Baptist. When the priest requesting the permits tried to go to the municipal authorities for permission, as would other nongovernmental institutions, those authorities insisted that the Communist Party review the request.99 On September 7, 1998, Cuban authorities allowed approximately 1,000 people to take part in a religious procession honoring the Virgin of Regla in Havana.100 But on the next day, the feast of Cuba's patron saint, the Virgin of Charity of Cobre, seven activists could not attend the festivities because they were under arrest, while state security agents prevented thirty others from attending by not allowing them to leave the Havana home of Isabel del Pino Sotolongo of the Christ the King Movement church.101

Cuba allowed unprecedented access to its national airwaves during the papal visit, but has provided little opportunity for religious institutions to broadcast their message since that time. Cuba has no independent radio or television stations. While the government maintains tight control over the printed word, a few churches have been able to publish religious newsletters with limited circulation in recent years. Protestants and Catholics, in particular, continue to push for furtheraccess to the state-controlled airwaves.102 On December 25, 1998, Cuba permitted Cardinal Jaime Ortega, the leader of Cuba's Catholic church, to deliver a Christmas message on the government's national music radio station, which reportedly has a small listening audience.103

One of Cuba's most prominent dissident organizations, the Christian Liberation Movement (MCL), under the direction of Oswaldo Payá Sardiñas, has been trying for a few years to get 10,000 signatures on a petition for political reform, in the hope that it would lead to a referendum. Payá Sardiñas has been outspoken in his calls for religious rights, such as the freedom to build churches and offer religious education, as well as related rights, such as forming independent associations and releasing political prisoners.104 The MCL's activities have resulted in government pressures. In February 1997, a Cuban court convicted MCL member Enrique García Morejón, who had been gathering signatures for the petition, of enemy propaganda and sentenced him to four years in prison.105 Cuban government officials have denied several requests from Payá Sardiñas to leave the country for MCL-related events, most recently in October 1998, when migration authorities refused permission for him to attend a human rights conference in Poland.106

Impediments to Humanitarian Aid Programs

Religious institutions such as the Catholic organization Caritas have assumed increasingly important roles in the provision of humanitarian aid to the Cuban population. The Martin Luther King Center, which maintains close government ties under the direction of Raúl Suárez, a Baptist pastor and member of Cuba's National Assembly, also undertakes humanitarian aid projects.107 In October 1997,Religious Affairs Director Caridad Diego notified religious groups carrying out humanitarian work that the Commerce Ministry had passed Resolution 149/97 (on August 4, 1997), which created restrictions on institutions' purchases from Cuban government stores.108 The resolution bars wholesale purchases from any entity but the government's EMSUNA Corporate Group (Grupo Corporativo EMSUNA). Diego apparently told some religious leaders that the restrictions were in response to churches allegedly having acquired illegal products, having abused their right to buy from state stores, and having trafficked materials on the black market.109

The resolution bars religious institutions from purchasing fax machines, photocopiers, and other electronics.110 Since Cuba criminalizes clandestine printing and enemy propaganda, and the government has seized computers, faxes, and photocopiers from dissident groups, this measure appears designed to impede religious groups freedom of expression.111 The law also creates cumbersome notification requirements. Institutions planning purchases from the government must provide sworn statements, signed by "accredited and recognized authorit[ies]" in the institution, detailing what each product will be used for and confirming that they will be used only for that purpose and will not be given to any other church entitity.112 Since many religious groups operate without official government recognition, such as the Catholic church's human rights group, the Justice and Peace Commission (Comisión Justicia y Paz), they would not be able to make any purchases under this provision. Humanitarian organizations cannot make any food purchases without giving the government thirty-day advance notice.113 In order to buy personal hygiene products for homes for the elderly, children, and the physically handicapped, sanatoriums, and residences for those suffering fromleprosy, the resolution requires the religious group to provide sworn declarations of the number of persons residing in each site.114

While Cuba can legitimately exercise its right to ration essential supplies, these restrictions impede free expression and create unreasonable limits on the capacity for religious institutions to carry out humanitarian efforts. One lay activist said that "'the message of the new regulations is that the churches...were doing too much, they were too active.'"115

Restrictions on Religious Visits to Prisons

The government's restrictions on pastoral

visits to prisoners are detailed above, at General Prison Conditions:

Restrictions on Religious Visits.

77 Tim

Golden, "After a Lift, Cuban Church has a Letdown," New York Times,

September 13, 1998.78 There

is some cross-over in the numbers of Catholics and believers in Afro-Cuban

rites, since the Afro-Cuban religions often require believers to be baptized

as Catholics. Practitioners of Afro-Cuban rites faced serious impediments

to practicing their faith in the aftermath of the revolution. However,

in 1978, the government apparently began promoting several Santería priests-called

babalowas-who one expert referred to as "diplo-babalowas," as a tourist

draw. Juan Tamayo, "In Cuba Clash Between Religions: Afro-Cuban Creeds,

Catholics at Odds," Miami Herald, January 12, 1998. 79

"Se

Abre Espacio para Testigos de Jehová," Reuters New Service printed

in El Nuevo Herald, December 26, 1998.80

Human Rights Watch telephone

interview with Damian Fernández, Ph.D., professor of international relations,

Florida International University, Miami, July 15, 1998. Gillian Gunn, Ph.D.,

"Cuba's NGOs: Government Puppets or Seeds of Civil Society?" Cuba Briefing

Paper Series: Number 7, Georgetown University Caribbean Project, February

1995.81

Juan

O. Tamayo, "Cuba has Long Spied on Church," Miami Herald, January

21, 1998. One of the defectors, Dariel Alarcón, a former army colonel,

told the Miami Herald that he had helped frame a Catholic priest

accused of assisting an anti-Castro hijacker who had killed a flight attendant

in 1966. Alarcón said that Father Miguel Laredo, who served ten years

in prison, was innocent. The government's intelligence-gathering methods

are further discussed above, at Routine Repression. 82

Constitution

of the Republic of Cuba (1992), Articles 8 and 55. The constitution and

Criminal Code provisions on religion and other fundamental freedoms are

discussed in detail above, at Impediments to Human Rights in Cuban Law:

Cuban Constitution and Codifying Repression. 83

Criminal

Code, Article 204. This provision is discussed above, at Codifying Repression.84

For

a detailed discussion of this decision, see Roman Orozco, Cuba Roja

(Buenos Aires: Información y Revistas S.A. Cambio 16 - Javier Vergara

Editor S.A., 1993), pp. 587-590. 85

Frances

Kerry, "Spirits in Soup Tureens Await Pope in Cuba," Reuters News Service,

January 15, 1998; and Homero Campo, "El Gobierno les Ve con Recelo y las

Somete a Estrictos Controles," Proceso, May 18, 1997.86

"Pese

a sus errores la Revolución ha Sido una Bendición," Granma, April

15, 1990, as cited in Orozco,

Cuba Roja, p. 599.87

Tim Golden, "After a Lift, Cuban

Church has a Letdown," New York Times, September 13, 1998.88

Orozco,

Cuba Roja, pp.

594-596.

Religious Leaders In Cuba Outspoken And Critical Of Proposed Constitution

Evangelicals pray during a church service in Havana, Cuba. Religious groups on the island have come out in opposition to a new constitution which will be voted on on Sunday.

People in Cuba vote Sunday on whether to make socialism "irrevocable" on the island and establish the Cuban Communist Party officially as the "supreme guiding political force" in the state and society.

In recent weeks, debate around those propositions has been unusually intense for an island not known for democratic processes, and it has featured the growing strength of religious leaders.

The political and ideological monopoly would come via a new constitution that Cubans can either endorse or reject in a popular referendum. The draft document, prepared under the guidance of the Communist Party, would replace the current Soviet-era constitution, adopted in 1976 and amended numerous times in subsequent years.

No opposition parties are allowed in Cuba, but in the deliberation over the proposed constitution, religious groups on the island have taken a lead in criticizing the government plan, revealing a level of influence they have not previously demonstrated.

Catholic bishops in Cuba have been particularly outspoken, issuing a joint statement earlier this month that noted how the document "effectively excludes the exercise of pluralist thought regarding man and the social order."

In an objection reminiscent of religious freedom debates in the United States and other countries, the Catholic bishops argue that "the free practice of religion is not merely the freedom to have religious beliefs but the freedom to live in conformity with one's faith and to express it publicly."

The government reaction to the church criticism came swiftly. Mariela Castro, the daughter of party leader Raúl Castro and a leading member of the National Assembly in Cuba, shared a post on her Facebook page calling the church "the serpent of history."

The government's campaign to promote a "yes" vote in the constitutional referendum has also encountered fierce opposition in the growing evangelical community. An early version of the constitution defined marriage simply as "the union of two persons," which conservative Christian leaders saw as an implicit endorsement of gay marriage.

"We love the sinner, but there are some practices that are not in accord with our biblical principles," says the Rev. Moises de Prada, president of the Assembly of God denomination in Cuba.

In their joint statement, the Catholic bishops made the same objection to the marriage article. "Given its importance for the future of the family, the society, and the education of new generations," the bishops said, "it's natural that this article was the one that most alarmed our population." The bishops said opposition to the marriage article was widely evident among Cubans as a whole.

In what appeared to a recognition of the opposition to the marriage article, the committee drafting the new constitution removed the reference in the final draft. Communist party leaders, however, denied the move came in response to the criticism, and they promised to revive it as part of a new family law.

This uproar over the proposed constitution marks another turning point in the Cuban government's ever-shifting attitude toward religion. In the early years of the revolution, the Catholic church in particular was subject to severe repression. Relations with the church improved in the period after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, when Cuban leaders were seeking alliances with western countries to make up for the loss of subsidies from former Communist allies. The Catholic church was revived, and evangelical Protestantism gained new ground.

The new churches enjoyed relatively good relations with the government for a while, but in recent years tensions have been rising.

"Evangelism for me doesn't live just within the four walls of the church," says Pastor Mario Felix Lleonart, who founded a Baptist church in the town of Taguayabón, in the province of Villa Clara. "Our faith doesn't just free us from the eternal consequences of sin. It also makes us free here on earth, and that brings us into conflict with a totalitarian regime that restricts our freedoms."

After starting a Christian blog in his community, Lleonart faced harassment from local Communist party leaders.

"They would tell me, 'Pastor, you could be better in your pastoral work if you stuck to teaching songs to your congregation and talking about the Bible and staying inside the church,'" Lleonart said. "They told me I was mixing with too many delinquents." After his children began suffering the consequences of his activism, Lleonart and his family sought political asylum in the United States.

Some articles in the new Cuban constitution suggest a further hardening of government attitudes toward religion, according to an analysis by Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), a religious freedom advocacy group based in the United Kingdom.The new constitution does guarantee religious freedom and freedom of conscience. Under the previous constitution, however, those provisions were tied together. In the new version, they are separated, and the freedoms are not defined as clearly as they were before.

"At least the language was there [previously]," says Anna-Lee Stangel, CSW advocacy director for the Americas. "Now that seems to be taken away. I don't think it's necessarily going to change things hugely but I do think it's symbolic. And if the language is going backwards, even symbolically, that's significant."

An especially big problem for religious and other opposition groups is that the guaranteed right to freedom of conscience is not actually guaranteed; it cannot be invoked to get around other constitutional provisions, like the ones officially establishing the Communist Party as the "supreme guiding power" and declaring the socialist system "irrevocable."

Thus, there may be freedom in Cuba, but not if it is used to oppose Communist rule.

In the weeks leading up to the constitutional referendum, Cuban religious leaders say they have come under intense pressure to urge their congregants to vote Yes.

"If a pastor dares in church to raise some criticism of the constitution, he's branded a counter-revolutionary," says Rev. de Prada.

Given the government's tight control in Cuba, the new constitution is virtually certain to be approved in this weekend's referendum, but the deliberation over its provisions appears to have given energy to a new church-based opposition movement on the island.

https://www.npr.org

Cuba ramps up religious persecution after election

HAVANA (BP) — Cuban pastors fear the government will further restrict religious freedom after clergy actively opposed the nation’s new constitution, a religious liberty advocate said today (Feb. 28).

Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), tracking religious persecution in Cuba and 20 other countries, said the Cuban Communist Party (CCP)is fearful of pastors because they sway public sentiment.

“We’ve seen the churches, particularly the Protestant churches, mobilize in a way they never have since 1959 in the past few months against the constitution and they’ve become very vocal,” Anna Lee Stangl, CSW joint head of advocacy, told BP.

“That’s always something the government has feared. They’re aware of the role religious groups played in the downfall of communism in Eastern Europe for example,” she said. “And so they’ve always tried really hard to divide the churches, to shut them up, to really scare them.”

The government does not use physical violence against pastors, Stangl said, but has detained pastors for hours and used various methods of intimidation to force pastors to support the communist party, such as threatening to limit educational opportunities for their children.

The new constitution, approved with 86.6 percent of a nationwide vote Feb. 24, remains largely symbolic, Stangl said. Laws dictated through administrative codes are oftentimes not available to the public. Codes are used to restrict the practice of religion, requiring churches to register with the government and to hold church events only after securing permits, which can be delayed for years.

“I think nobody expected things to change drastically with the new constitution,” Stangl said. “But just the fact that the Cuban government found it important enough to weaken the language even further is indicative to us that they intend to go in an even harsher direction.”

The government is likely preparing an intense wave of Christian persecution, Stangl believes.

“I think me and a lot of other people I know who observe religious freedom in Cuba are expecting some sort of major crackdown,” she said, “because the government does not want the churches to be united in the way they are.”

A cross-denominational group of Christian leaders, led by the Methodist Church of Cuba and Assemblies of God, was ignored when it called for changes to the proposed legislation in advance of the election, and the government pressured pastors to support the referendum.

Pastors campaigned to amend constitutional language that defined marriage as between “two people,” as opposed to one man and a woman. But the government responded by dropping the clause entirely. Likely, legal codes affecting families, “family codes,” will be used to usher in gay marriage, Stangl said.

The new constitution drops the state’s recognition of “freedom of conscience and religion” and no longer recognizes an individual’s right to change their religious beliefs or to profess a religious preference. Instead, the constitution simply “recognizes, respects and guarantees religious freedom,” according to a CSW press release. Also, the new constitution states that religious and state institutions both have the same rights and responsibilities.

In its reports today of harassment and persecution, CSW named three pastors who were detained for hours in the days before and after the Feb. 24 election. Christian literature was described as “against the government” and confiscated from two high-profile pastors in the Apostolic movement, CSW said. Hired drivers employed by the government were fired for giving rides to church members, and the government has withdrawn permits required for church events where foreign missionaries were scheduled to speak.

Pastor Sandy Cancino, an outspoken opponent of the new constitution, was blocked from voting at the Cuban Embassy in Panama despite having the proper identification and documentation, CSW said.

“It’s horrible what is happening in our country,” CSW quoted another church leader, who said the government has become paranoid. “A friend in my church was fired from his job. A 16-year-old student was questioned on how she was going to vote and because she said ‘no,’ they issued a pre-arrest warrant against her and took the case to the municipal level…. There are many other [similar] stories.”

Cuba is already a USCIRF Tier 2 “country of particular concern” for religious liberty violations noted in the USCIRF 2018 Annual Report. The CCP threatened to confiscate church property, repeatedly interrogated and detained religious leaders, prohibited Sunday worship and controlled religious activity, USCIRF noted.

Only 5 percent of Cuba’s 11.147 million people are Protestant, according to the U.S. Department of State. As many as 70 percent are Roman Catholic, mixed with traditional African religions including Santeria, the State Department said. A quarter of Cubans are religiously unaffiliated.

https://www.baptistpress.com

READ MORE CLICK HERE

Regimes target the faithful in Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela

‘Castro’s death won’t end repression of Cuban Church’

The death of Cuba’s revolutionary leader Fidel Castro will not reduce the harassment and surveillance to which the Church is already subjected, an analyst at the charity Open Doors has warned.

Following Castro’s death at the age of 90 on Saturday (26 Nov.), Paul Groen told World Watch Monitor: “Fidel’s regime really has been a huge source of suffering for the Church,” referring to the communist rule instigated by Castro and other revolutionaries in 1959 and continued by Fidel’s brother Raul since 2006. “Many leaders don’t expect any immediate change. Raúl Castro will continue governing the way his brother did. This means that the restrictions on the Church that existed before Fidel’s death are likely to be maintained, at least until the elections in 2018 when Raúl, who will then be 87, has said he will resign as president.”

Cuban church leaders chose not to comment publically on Castro’s death. The Catholic bishops’ conference in Havana issued a brief and carefully worded statement expressing “our condolences to his family and the authorities of the country”, entrusting the communist leader to Christ, “the Lord of Life and History”, and praying “that nothing would disrupt the coexistence among Cubans”.