APRIL 2021 - ISSUE 200 COPIES -

Cuba: 60 Years of Revolution, 60 Years of Oppression

Last month, the Cuban regime reportedly released over 6,500 prisoners to curb the spread of COVID-19. It was also reported that more than 300 people were imprisoned for “spreading an epidemic” by refusing to wear face masks.

It is unclear whether political prisoners were among those granted an “early release,” but pursuant to a petition signed by Cuban organizations operating in exile, political prisoners continue to be subjected to the most deplorable conditions during the pandemic.

The Cuban regime’s actions clearly demonstrate the implementation of repressive policies under the guise of “modernization” — further entrenching the government’s totalitarian dictatorship.

Introduction

Cuba is the largest island in the West Indies archipelago, positioned at the intersection of the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea. Roughly 90 miles north of the country is the United States’ Straits of Florida.

Cuba has been under authoritarian rule since 1952, when dictator Fulgencio Batista took power. As Batista made fortunes and built up his influence over the country, he developed a reputation as a corrupt and ruthless ruler. He controlled the press, suspended free and fair elections, and banned protests. Batista was overthrown in 1959 by a coup d’état, or “revolution” led by Fidel Castro, which resulted in Castro’s political domination, and condemned the island to continued isolation from the rest of the world, even today.

Castro imposed severe internet censorship and state-controlled media regulations, and the Cuban government continues to have the most repressive media conditions in the Americas. Reporters Without Borders ranked Cuba 171 out of 180 countries on its 2020 Press Freedom Index.

Behind Castro’s revolutionary image was a lethal intent: he used his influence as an oppressor to persecute and punish those who engaged in dissent and opposed his dictatorship. Fundamental freedoms — particularly civil and political rights — were abused, and thousands of Cubans were imprisoned, beaten, and executed.

In the 1960s, the regime even went as far as profiting off of these executions by harvesting the blood of political prisoners prior to their execution. Roughly seven pints of blood were harvested from each prisoner, resulting in their state of paralysis. They were then lifted on stretchers, executed by firing squad, and buried in common graves. The Cuban government proceeded to sell their blood at $50/pint to Communist Vietnam.

Not even children were spared from the waves of arbitrary imprisonment and execution. According to Cuba Archives, at least 22 minors were killed by firing squad and 32 by extrajudicial killings under Castro’s regime.

These horrific acts of exploitation and injustice are only glimpses into Castro’s dark legacy.

Political Regime Type

At the end of 1958, Fidel Castro and his rebel forces began the process of ousting Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Their efforts and preparation, however, had begun years earlier when Batista canceled the 1952 Cuban elections and seized power. Fidel Castro, who was running for a seat in congress, was thus deprived of his opportunity to be elected. He subsequently began leading a “Movement” to purportedly return the Caribbean island to a democratic nation.

In January 1959, Fidel Castro and his rebel forces — including Raúl Castro, Ché Guevera, and Camilo Cienfuegos — finally entered Havana and began to centralize their power, unilaterally determining how the country would operate. Although Castro claimed to be a democratic nationalist, his consolidated power quickly led to the rounding up and execution of approximately 500 remaining Batista officials.

Fidel Castro became largely influenced by socialism and communism. After demolishing the remains of Batista’s era, he quickly allied with the Soviet Union, which provided Cuba with substantial agricultural support and subsidies. The two countries’ alignment provoked the United States during the Cold War era and brought about international events including the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis. In addition, the United States imposed a trade embargo in 1962.

Castro’s government formally proclaimed Cuba a socialist state in 1961. The announcement was made one month after the failed United States-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion, which resulted in the imprisonment and execution of hundreds of anti-Castro rebels. Fidel Castro then declared the annulment of elections, which consolidated his power and was later enshrined in Cuba’s 1976 constitution.

The 1976 constitution, which formally entrenched socialist domination, was inspired by the ideologies of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Criticism toward the constitution was rooted in how it was drafted, and the mechanism that determined its approval. Lack of citizen participation regarding the drafting of the constitution was a major deficit. The referendum was established by the Communist Party and the National Assembly — overseen by Fidel Castro — whose members were not elected publicly. The constitution, which controlled every aspect of citizens’ way of life, ultimately gave the regime the capacity to crush any and all dissent.

Upon the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Cuba entered into what was euphemistically called a Special Period, which included food rationing, gasoline shortages, and the proliferation of small-scale gardens for Cubans to meet basic nutritional needs, among other things. While spreading propaganda internationally about the implementation of universal health care and education, he left Cubans without economic opportunities and liberty, which was particularly devastating during the Special Period.

Half a decade later, Cuba’s economy began to stabilize as its human rights record continued to decline. In 2003, Cuba’s “Black Spring” drew international condemnation when 75 journalists were arbitrarily arrested, tortured, and detained. These journalists were held on spurious charges, subjected to show trials, barred from consulting with legal counsel outside of the courtroom, and denied medical care while in prison. Many of these political prisoners languished in prison for years. Among them was human rights activist Omar Rodriguez, who was arrested for his involvement in the Varela Project, a draft bill spearheaded by prodemocracy activist Oswaldo Payá that proposed a referendum in which Cubans would decide on reforms that would enable the effective respect of fundamental rights.

That same week, three men attempted to reach the United States by hijacking a ferry. Days later — after a show trial — they were executed by firing squad for what the government claimed to be acts of terrorism. Four other men who had aided in appropriating the boat were sentenced to life in prison.

The Cuban regime’s systematic repression represents the widespread sense of injustice that permeates the island. For example, Cuba’s anti-expression law, Decree 349 — one of the first laws signed by Mr. Díaz-Canel — came into force in 2018 and requires artists, musicians, and writers to receive governmental approval prior to presenting their work publicly or even in the privacy of their homes. The decree allows the Ministry of Culture to suspend performances and advise on cancelling the authorization to engage in artistic work altogether. These judgments can only be appealed before the very same Ministry of Culture, as opposed to an independent and impartial body.

Decree 349 builds on an already existing system of laws and regulations that threaten freedom of expression. The Decree is wholly inconsistent with international human rights standards, jeopardizes free speech and liberty, and is ultimately intended to silence voices that criticize the government. The law’s language is extremely broad and prohibits, for example, the “use of patriotic symbols that contravene current legislation” and “anything that violates the legal provisions that regulate the normal development of our society in cultural matters.”

Cuba’s “New” Constitution

In February 2019, the 1976 constitution was replaced with a new constitution through an orchestrated referendum process. Approximately 86.9% of voters of the roughly 8 million who voted, supported the referendum.

While a voter turnout of nearly 87% would be considered very high for democracies around the world, in Cuba’s case, it’s the natural outcome of a tightly controlled process whose sole purpose is to secure a predetermined result.

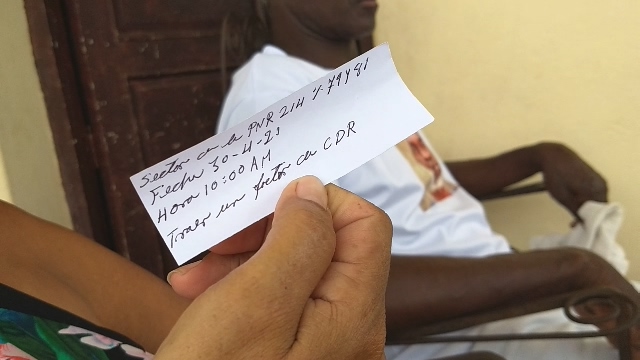

Government officials go door-to-door coaxing citizens to go to the polls, and political dissident Antonio Rodiles notes that voter turnout is typically extremely high “because even though people know it’s theater, they also know that they keep track of who votes.” Michael Svetlik, vice-president of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, confirms that elections are typically rigged in authoritarian regimes, and that citizens vote out of fear of punishment. The Cuban regime’s system is no exception; there are no political opposition parties or secret votes to challenge the constitution or regime, so referendums are not free or fair.

Dissidents, who deemed the political process fraudulent, reported that citizens were temporarily detained for either voting “no” or abstaining from voting altogether. The referendum triggered arbitrary arrests across the country and led to the detention of over 400 citizens, as well as a minimum of “48 acts of harassment and 12 physical attacks.”

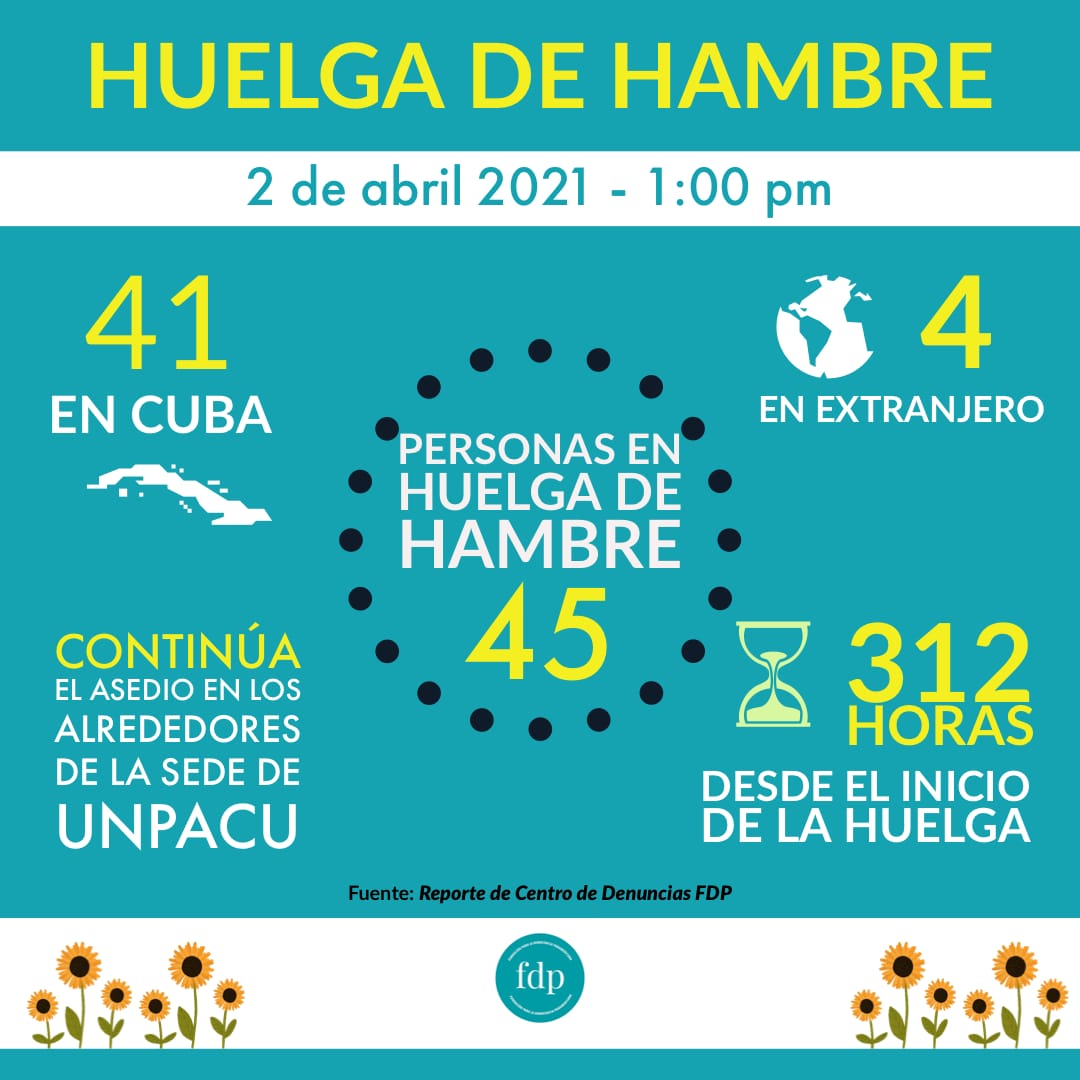

The police also raided homes of opposition activists and threatened dissidents, warning that “the next time they will end up in a jail cell,” when referring to activists who had given a workshop on voting observation. José Daniel Ferrer, for example, who promoted the “No” vote in a public park, was detained and, alongside 70 other members of his organization, went on hunger strike to protest the Cuban government’s monolithic state.

The new constitution preserves Cuba’s one-party socialist system and is “committed to never returning to capitalism as a regime,” yet this time openly endorses foreign investment (Article 28). While in theory the new constitution reflects some of the proposed changes that were put forth by Cuban citizens, Cuba’s authoritarian regime continues to actively oppress Cuban citizens by withholding fundamental rights of expression.

For example, citizens campaigned for a constitution that would pave the way for same-sex marriage. However, the Drafting Commission removed gender-neutral descriptions of marriage and left members of the LGBTQ community without equal rights. In addition, Cuban citizens are able to “combat through any means, including armed combat when other means are not available, against any that intend to topple the political, social, and economic order.” The term “topple,” however, is not defined in the constitution and could be used broadly to target dissidents for political reasons. Furthermore, while the state now prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation (Article 42), protects women from gender violence, and safeguards their sexual and reproductive rights (Article 43), gender and sexual equality continue to be theoretical and abstract improvements. Women are consistently excluded as decision makers, and fall victim to horrific forms of domestic abuse that have only escalated during the COVID-19 quarantine. Yoani Sánchez, a celebrated Cuban blogger and prodemocracy activist, provides a list of resources that Cuban women so desperately need including, shelters for battered women, fair pay, and the opportunity to assume government positions.

Perhaps most notably, the new constitution limits the president’s term to two consecutive periods of five years and highlights that, similar to parliamentary systems, the president will be selected by the National Assembly (Article 126), which may seem like a significant change from the previous era of Castro rule for nearly six decades. However, in practice, the Cuban regime remains a fully authoritarian regime without an independent judiciary or lawful administration of justice by which to hold the government accountable.

The Economy

Fidel Castro relinquished most of his power in 2008, and appointed his hand-picked successor, his brother, Raúl Castro, as Head of State. Raúl’s presidency supposedly resulted in the expansion of the economy, allowing for foreign investment, the buying and selling of property, and permitted entrepreneurs to open small businesses. In addition, Cubans gained access to cellphones, computers, and the internet.

In 2014, Raúl Castro and then-President of the United States, Barack Obama, announced a prisoner exchange and the restoration of diplomatic relations, further presenting the façade of a modernizing Cuba. However, in the background of these developments, Raúl Castro continued to implement many of the abusive tactics that his brother had relied on. For example, a “dangerousness law,” gives the state permission to incarcerate citizens based on a suspicion that they might perpetrate crimes in the future, rather than on the basis of actually having committed a crime. The existence of such legislation allows for an overly broad application of the law, thus enabling the regime to crackdown on various forms of dissent.

Critics of the Cuban regime assert that Raúl’s presidency did not result in the expansion of the economy, and that reforms have been slow and subject to several restrictions. Roughly 12 percent of the country’s G.D.P, generated through private businesses, is heavily controlled by the state. Ministries that operate on national, provincial, and municipal levels have the authority to oversee and report on private businesses under their jurisdictions. These ministries subject business owners to overwhelming requirements and permit government officials to enforce heavy fines, suspend licenses, and seize properties. Furthermore, Cuban citizens are only permitted to acquire one license for one business, blocking them from diversifying their trades.

Other regulations that have prevented the growth of the private sector or imposed restrictions on it include the demand that private taxi drivers document their fuel purchases from government gas stations, preventing them from purchasing fuel on the black market. The informal economy, however, provides a critical means for innovation, autonomy, and entrepreneurialism that is otherwise stifled by state control. In addition, restaurants and bars have set capacities at 50 customers. Furthermore, daycare centers must apportion a minimum of two square meters per child, with no more than six children per daycare aide. Perhaps most damaging, are the laws that enforce an upward-sloping wage scale. Wages increase as more employees are hired, becoming acutely expensive and inaccessible to the average business owner, who earns a salary of roughly $32 per month. Meanwhile, farmers are forced to sell their crops at prices set by the state and that are below market value, rather than being allowed to sell their crops at prices set by supply and demand.

Amid a deepening economic crisis, the government imposed price controls that apply to state-run companies, as well as private sector cooperatives, farmers, small businesses, and self-employed citizens. Pork, for example, which was previously set at 65 pesos per pound is now set at 45 pesos per pound, illustrating the loss of income that farmers have to bear when their monthly wages are already so meager. “With the new prices we are super asphyxiated because the farmer who moves his pigs to Havana still charges 28 pesos a pound,” said Mr. Soler, who is a Cuban butcher. These measures of control indicate the government’s unwillingness to support the expansion of the economy, and, according to Paul Hare, the former British ambassador to Cuba, they also indicate that the Cuban regime is worried about the influence of self-employed and cooperative businesses in the agricultural sector. The government’s control over supply and demand creates an economy that does not conform to citizens’ needs, and effectively damages their standard of life.

The state’s control over the private sector confirms that the regime’s expansion of the economy is deeply superficial. Rather than promoting a capital-rich and diversified economy, the state suppresses any competition against its political interests.

In 2018, Miguel Díaz-Canel succeeded Raúl Castro as President of Cuba. He is the first person outside of the Castro family to take power since the Cuban Revolution over half a century ago. His election, however, did not take place in the context of a free and fair election. He was selected by the National Assembly as their sole candidate, which ensured his appointment and the continuation of Cuba’s one-party state.

While cell phones, computers, and the internet exist within Cuba’s economy, President Miguel Díaz-Canel continues to restrict Cuban citizens’ access to the mobile internet through prohibitively high pricing; four gigabytes of data, for example, cost roughly $30 per month, which is equivalent to the average monthly salary of most citizens. The internet also continues to be heavily censored by the state. The Cuban regime actively blocks independent news, as well as websites that oppose the government and advocate for fundamental reform.

Healthcare and Education

The Cuban Revolution may be seen by some as having transformed the country, in terms of both challenging foreign interests and policy and how Cubans structure their daily lives, inspiring many who have stayed in the country, as the state has claimed to make improvements to healthcare, education, and literacy, and initiated international humanitarian missions.

However, the Cuban Revolution has also pushed millions of people to leave the country. Sixty-one years after Fidel Castro’s coup d’état, the revolution’s darker legacy continues to pervade Cuban society. The state’s revered social system is simultaneously a system of near-universal poverty. Universal healthcare and education mean little if medical products are depleted, if machinery is outdated, and if buildings are crumbling. Sources convey that medicines are missing, and that entire shelves at pharmacies are bare. Those who fall ill are often expected to bring their own sheets, food, and water to the hospital.

Hilda Molina, the former chief neurosurgeon in Cuba, has lamented over the state of Cuba’s health sector and described the politicization of the health system by the Cuban regime, where control is exerted over medical and scientific institutions, universities, and professionals. Within this context, medical statistics are managed — and often falsified — by the state, as opposed to independent experts. Dr. Molina also revealed that sewage and garbage are often strewn along streets, contaminating the country’s drinking water supply and further entrenching deficient and dangerous health conditions.

The Cuban regime hinders doctors’ capabilities under a highly controlled system that stifles medical progress. The country’s closed society bars health care professionals from traveling, consulting, and engaging with other medical experts in the international community, which affects their ability to receive up-to-date information and collaborate with others in innovative ways.

While Cuba’s “esteemed” medical missions are often doted on by the media and host governments around the world — including a recent COVID-19 mission to Italy — they are unjust as they represent a modern form of slavery. Cuban doctors commonly share stories of their forced participation into Cuba’s medical missions and describe strict regulations enforced by the Cuban regime in order to prevent them from defecting while they are overseas. They report being surveilled by Cuban authorities while abroad, having their passports confiscated, and being subjected to horrific forms of intimidation, including sexual harassment and abuse. Some doctors have revealed that they were stationed in areas infiltrated by criminal gangs, and were threatened at gunpoint. Despite their perseverance through these dangerous conditions, doctors are only paid a fraction of what they are owed, while the rest of their remuneration is funneled back to the Cuban regime. The UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery and the UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons even noted that, “forced labor constitutes a contemporary form of slavery,” in their letter to the Cuban regime in 2019.

In addition, Cuban doctors have noted that they are often coerced into falsifying statistics and political propagandizing. Doctors are forced to falsify statistics while they are overseas — inventing patients and clinic visits — because amplifying their medical missions’ efficacy permits Cuban officials to demand more payment from various host countries. Thaymi Rodríguez, a dentist who was stationed in Venezuela, confesses that she was obligated to see 18 patients a day, but might only see five. As a result, she would have to throw away leftover medicine, “because we simply had to,” expressing how painful it was to throw away medicine in countries where it is so greatly needed.

These abuses revealed by Cuban doctors, coerced into participating in the state’s medical missions, highlight the Cuban regime’s exportation of corruption and exploitation abroad.

As for the education system, sources contend that Fidel Castro did not help Cuban citizens achieve literacy. Cuba already had near-universal education and high literacy rates prior to the revolution in 1959. In addition, according to data collected by Carmelo Mesa-Lago, a professor emeritus of Pittsburgh University and expert on Cuba, the economic crisis of the 1990s — which caused the economy to plummet by 35% — resulted in the deterioration of the education system. Cuba’s education system has yet to recover, and education indicators remain below 1989 levels.

In addition, low wages and lack of incentives prompt teachers to emigrate or abandon their professions for more lucrative opportunities. Educators’ salaries are insufficient to maintain an adequate quality of life, and serve to reinforce an educational system that is deeply flawed and unjust. The Cuban regime controls the education sector to promote a revolutionary psychology that in turn sustains the socialist state. As Fidel Castro once said: “The universities are only available to those who share my revolutionary beliefs.”

Case Studies

As has been made clear, Cuba is not a democratic country where there is independence and separation of powers. Under this type of regime, there is no guarantee of independence in the administration of justice which will be highlighted through the following case studies.

Oswaldo Payá and Ángel Carromero

On July 22, 2012, Oswaldo Payá and his young associate, Harold Cepero, died in a car crash in eastern Cuba. The circumstances of the crash are still in dispute and cannot be determined without an independent investigation.

Mr. Payá was one of Cuba’s most celebrated human rights activists and dissidents, championing peace and civil liberties, and was a recipient of the 2002 Sakharov Prize, which is awarded to an individual who fights for human rights and fundamental freedoms. He was the founder and leader of the Varela Project, a petition drive calling for a referendum in which Cubans would decide on legal reforms to guarantee freedom of speech and assembly, among other fundamental rights. Formally, the Cuban constitution allows citizens to introduce legislative reform if they collect 10,000 citizen signatures, and Oswaldo Payá successfully collected over 11,000.

Despite his peaceful efforts, Mr. Payá endured continuous harassment and intimidation by the regime. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has denounced the Cuban government’s harassment and persecution against civil society groups and human rights defenders since 1962, and noted that “for decades the Cuban State has organized the institutional machinery to silence voices outside the regime, and to repress independent journalists, as well as artists or citizens who try to organize themselves to articulate their demands.”

The government has alleged that the car crash that killed Mr. Payá and Mr. Cepero transpired when the driver, Ángel Carromero, a former youth leader of Spain’s ruling party, lost control of the vehicle and crashed into a tree. They determined that the crash happened because of the speed at which Mr. Carromero was driving, and because of his abrupt braking when the car was on a slippery surface. Mr. Carromero was subsequently convicted of vehicular manslaughter and sentenced to four years in prison. He has since been released to Spain to serve out the remainder of his term.

Cuban dissidents and Mr. Carromero, however, have a different account of those same events that unfolded in 2012. In an interview with The Washington Post, Mr. Carromero asserted that government officials followed his car and rammed into it, resulting in the deaths of Mr. Payá and Mr. Cepero, and in his own loss of consciousness. Once taken to the hospital, Mr. Carromero was surrounded by government officials who ruthlessly dismissed his details of the accident. He was drugged and coerced into signing statements with fabricated, self-incriminating evidence. According to Mr. Carromero, the officers warned him that “depending on what [he] said things could go very well or very badly for [him].”

In addition, his false confession was broadcasted on television under deplorable conditions. He was held incommunicado among cockroaches and other insects, with a toilet that lacked a tank, while water streamed from the roof. These forms of cruel and degrading treatment may amount to torture, and are in standing violation of Articles 18, 25, and 26 of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (“American Declaration”), and Articles 5, 8, 9, 10, and 11 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”), to which Cuba is bound. The UDHR expressly states that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

The Human Rights Foundation’s legal report on the state-sanctioned and premeditated murder of Mr. Payá extensively documents the cruelty of Cuba’s totalitarian regime to which Mr. Carromero also fell victim.

The Cuban regime systematically violates the due process rights of activists, particularly through trials that are purely symbolic and held to strengthen the regime, as opposed to finding the truth and administering justice. After his arrest, Mr. Carromero did not have access to legal counsel for many weeks, and later, had all of his conversations with his attorney overseen by a Cuban official. According to international human rights law, the right to defense counsel shall not be delayed, and opportunities to consult with a lawyer shall not be intercepted or censored.

In addition, during Mr. Carromero’s trial, his lawyers were prevented from accessing his case file or evidence on which his accusations were grounded. Mr. Payá’s family was never included in the investigation and was barred from attending Mr. Carromero’s trial.

Human Rights Watch has reported that political prisoner trials in Cuba are virtually-closed hearings that last less than an hour. The organization was unable to document a single case under Raúl Castro’s regime wherein a court had acquitted a political detainee. Mr. Carromero’s trial was no exception — the authorities barred the public from attending his trial and only permitted members of the Communist Party of Cuba into the courtroom. The openness of hearings, however, is imperative to assuring public confidence in the integrity of the legal system, as well as in the administration of justice.

Almost eight years later, justice has yet to be secured for Mr. Payá’s family and for Mr. Carromero. While the UDHR guarantees equality before the law, including the right to a fair and public hearing by an impartial tribunal, the Cuban regime continues to abuse its power for political purposes, and, ultimately, to act with impunity.

Ramón Velásquez Toranzo

At a press conference in 2016 with then-President of the United States Barack Obama, Raúl Castro unequivocally denied the presence of any political prisoners in Cuba. Human rights groups, however, continue to document the cases of Cuban dissidents who continue to be persecuted under the Cuban regime.

The Cuba Archives documented at least 500,000 people who have fallen victim to arbitrary detention since January 1, 1959; Ramón Velásquez Toranzo is one of them. On International Human Rights Day in 2006, Mr. Toranzo set out on a “march of dignity” with his wife Bárbara and their daughter, Rufina. While marching, they held signs that read, “respect for human rights,” “freedom for political prisoners,” and “no more repression against the peaceful opposition.” They called for the respect of their civil liberties, which are guaranteed under the UDHR, the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, and formally in the Cuban Constitution, but are ignored by the Cuban regime.

They marched silently, and, at night, slept on curbsides, at bus stops, and in the homes of those who offered shelter. They started in Santiago de Cuba and hoped to walk the entire length of the country, but were stopped and arrested on the outskirts of Holguín. The Cuban government’s rapid response brigade intimidated them with metal rods and threatened to rape Bárbara and Rufina. Four days later, when Mr. Toranzo was released from prison, they continued marching. State forces, however, continued to torment them by trying to run them over with cars.

They reached Camagüey — over 185 miles from where they began their march — on January 19, 2006, and were arrested again. After being detained for four more days, Mr. Toranzo was taken to a municipal court, where he was charged with “dangerousness,” subjected to a closed trial, and sentenced to three years in prison. Cuba’s “dangerousness” law permits Cuban authorities to incarcerate citizens prior to having committed any crime. Their imprisonment is based on suspicion that they might commit crimes in the future.

A former high-ranking judge revealed that legal cases against dissidents are managed by state security forces, and that judges often acquiesce to fabricated evidence. In Mr. Toranzo’s case, the regime’s evidence against him entailed “official warnings” for being unemployed; these warnings were presented while Mr. Toranzo was marching, and as a result, had never been seen by him. Furthermore, during Mr. Toranzo’s trial — which lasted less than an hour — the presiding judge called a recess to confront Mr. Toranzo’s legal counsel. Upon returning, Mr. Toranzo’s legal counsel stopped defending him and remained silent for the remainder of the trial.

The American Declaration expressly states that every person has the right to a fair trial, the right to protection from arbitrary arrest, and the right to due process of law. No one can be subjected to “cruel, infamous or unusual punishment.” After Mr. Toranzo’s sentencing, and in flagrant violation of his rights, he was stripped down to his underwear and detained in solitary confinement without a bed and in a cell that was flooded with water.

The Cuban regime not only torments political prisoners, but also preys on their family members. After Mr. Toranzo’s arrest, “Death to the worms of house 58” (his address) was spray-painted on a bus stop close to his home. This dehumanizing terminology, targeting political prisoners and their families, is common practice.

The regime also assigned a man near Mr. Toranzo’s home to follow the family. Cuban officials demanded that Rufina’s friends report on her activities, and the constant surveillance eventually led her to flee to the United States. Likewise, her brother René, reported monitoring by the state and noted that Cuban officials questioned everyone he interacted with.

The case of Mr. Toranzo is a looking glass into Cuba’s repressive government — a regime that is unrelenting in its abuse of power and denial of fundamental rights and freedoms.

Conclusion

Although Cuba’s constitutional referendum might have been propagandized as progress toward a more open society, President Díaz-Canel continues to implement the Castros’ dangerous, and sometimes deadly, tactics. The cases of Oswaldo Payá and Ramón Velásquez Toranzo are only two examples of the Cuban regime’s exploitation of justice.

In 2019, Cuban opposition members were consistently arbitrarily arrested, imprisoned, and tortured. There were reports of several cases of prisoners of conscience who were targeted for their peaceful beliefs, and the NGO Cuban Prisoners Defenders reported a minimum of 71 people who were incarcerated on political charges.

The real figures are likely to be higher, but the Cuban government prevents independent groups from entering the country to report on the human rights situation. In addition, the government’s censorship and state-controlled media silence Cubans who oppose the regime, continuing to cover up the government’s corruption and criminality. The state’s lack of transparency further entrenches the government’s totalitarian dictatorship, where even the most peaceful protesters are punished for calling for what they are owed: civil liberties and fundamental freedoms.

At the same time, Cuban artists, journalists, lawyers, and members of the opposition continue to languish in the Cuban gulags. We must speak up on their behalf and continue to echo their calls for freedom and the rule of law. While the Cuban regime continues to avoid accountability for its heinous crimes, we must end its culture of impunity by standing up for human rights and calling for the immediate and unconditional release of Cuba’s courageous human rights defenders.

The Cuban government continues to repress and punish dissent and public criticism. The number of short-term arbitrary arrests of human rights defenders, independent journalists, and others was lower in 2019 than in 2018, but remained high, with more than 1,800 arbitrary detentions reported through August. The government continues to use other repressive tactics against critics, including beatings, public shaming, travel restrictions, and termination of employment.

In February, a new Constitution of the Republic of Cuba was approved in a referendum, which entered into force in April. Prior to the referendum, authorities repressed activists opposing its adoption, including through raids and short detentions, and blocked several news sites seen as critical of the regime.

On October 10, Miguel Díaz-Canel was confirmed as president of Cuba with 96.76 percent of votes of National Assembly members.

Arbitrary Detention and Short-Term Imprisonment

The Cuban government continues to employ arbitrary detention to harass and intimidate critics, independent activists, political opponents, and others. The number of arbitrary short-term detentions, which increased dramatically between 2010 and 2016—from a monthly average of 172 incidents to 827—started to drop in 2017, according to the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation, an independent human rights group that the government considers illegal. The number of reports of arbitrary detentions continued to drop in 2019, with 1,818 from January through August, a decrease of 10 percent compared to the 2,024 reports during the same period in 2018.

Security officers rarely present arrest orders to justify detaining critics. In some cases, detainees are released after receiving official warnings, which prosecutors can use in subsequent criminal trials to show a pattern of “delinquent” behavior.

Detention is often used to prevent people from participating in peaceful marches or meetings to discuss politics. Detainees are often beaten, threatened, and held incommunicado for hours or days. Police or state security agents routinely harass, rough up, and detain members of the Ladies in White (Damas de Blanco)—a group founded by the wives, mothers, and daughters of political prisoners—before or after they attend Sunday mass.

In September, in an effort to prevent a demonstration organized by the Cuban Patriotic Union, authorities detained over 90 activists and protestors and raided the union’s headquarters, media reported. The protest supported the Ladies in White and other persecuted groups, and rejected the 2017 Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement between the Cuban government and the European Union. It coincided with a high level European delegation visit to Cuba.

Freedom of Expression

The government controls virtually all media outlets in Cuba and restricts access to outside information. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), an independent organization that promotes press freedom worldwide, Cuba has the “most restricted climate for the press in the Americas.”

A small number of independent journalists and bloggers manage to write articles for websites or blogs, or publish tweets. The government routinely blocks access within Cuba to these websites. In February, before the referendum on the new constitution, it blocked several news sites seen as critical of the regime, including 14ymedio, Tremenda Nota, Cibercuba, Diario de Cuba and Cubanet. Since then, it has continued to block other websites.

Only a fraction of Cubans can read independent websites and blogs because of the high cost of, and limited access to, the internet. In 2017, Cuba announced it would gradually extend home internet services. In July 2019, the government issued new regulations allowing for the creation of private wired and Wi-Fi internet networks in homes and businesses and to import routers and other equipment.

Independent journalists who publish information considered critical of the government are routinely subject to harassment, violence, smear campaigns, travel restrictions, raids on their homes and offices, confiscation of their working materials, and arbitrary arrests. The journalists are held incommunicado, as are artists and academics who demand greater freedoms.

In April, police agents detained Roberto de Jesús Quiñones, an independent journalist who publishes on the news site CubaNet, outside the Guantánamo Municipal Tribunal when he was covering a trial. They beat him while transporting him to the police station. Authorities released him five days later but initiated criminal proceedings against him. According to a local free speech group, in August a municipal court sentenced Quiñones to a year in prison on charges of “resistance” and, for failing to pay a fine imposed upon his release in April, “disobedience.” He was detained on September 11 and transferred to the Guatánamo Provincial Prison, where he was serving his one-year prison sentence at time of writing.

In July, Decree-Law 370/2018 on the “informatization of society” entered into force, making it illegal for Cubans to host their websites from a server in a foreign country, “other than as a mirror or replica of the main site on servers located in national territory.” Though the scope of the rule remains unclear, it could affect most Cuban critical independent news sites and blogs, which are purposely hosted abroad. It also prohibits the dissemination of information “contrary to the social interest, morals, good manners and integrity of people.” Violations can lead to fines and confiscation of equipment.

In April, Decree 349, establishing broad and vague restrictions on artistic expression, entered into force. Under it, people cannot “provide artistic services” in public or private spaces without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture. Those who hire or make payments to people for artistic services without authorization are subject to sanctions, as are the artists. Sanctions include fines, confiscation of materials, cancellation of artistic events, and revocation of licenses. Local independent artists have protested the decree, both before and after it entered force. Three were detained in December 2018 when attempting to join protests, media reported.

Political Prisoners

According to the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation, as of October, Cuba was holding 109 political prisoners. The government denies independent human rights groups access to its prisons. The groups believe that additional political prisoners, whose cases they have been unable to document, remain locked up.

Cubans who criticize the government continue to face the threat of criminal prosecution. They do not benefit from due process guarantees, such as the right to fair and public hearings by a competent and impartial tribunal. In practice, courts are subordinate to the executive and legislative branches.

In December 2018, activist Hugo Damián Prieto Blanco, of the Orlando Zapata Civic Action Front, was sentenced to a year in prison for the crime of “pre-delinquent social dangerousness.” Under the Penal Code, a person can be considered in a “dangerous state” when found to have a “special proclivity” to commit crimes—even before any have been committed—“due to conduct in clear contradiction to the norms of the socialist morals.” Zapata had been arrested in November 2018 when participating in a protest. In April, his sentence was suspended and he was released.

In May, after more than two years in prison, Dr. Eduardo Cardet Concepción, leader of the Christian Liberation Movement, was released with limits on his movement and activities. Cardet, a supporter of the “One Cuban, One Vote” campaign, had been sentenced to three years in prison in March 2017. During his imprisonment, he was held in solitary confinement and denied visits and contact with family members, even by phone. Authorities argued that family visits were not “contributing to his re-education.”

In October, José Daniel Ferrer, opposition leader and founder of the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), the largest and most active pro-democracy group in Cuba, was detained at his home by police forces. He has not been informed of any charges against him and has not been brought before a judge. He remained in detention at time of writing.

That same month, Armando Sosa Fortuny, the oldest political prisoner in Cuba, died from health complications at a hospital in Camague, where he was transferred from prison last August. Sosa had served 26 of a 30-year sentence issued in 1993 for illegal entry to Cuba and “other acts against the security of the state.” Sosa, a well-known dissenter, spent 43 of his 76 years imprisoned in Cuba.

Travel Restrictions

Since reforms in 2003, many people who had previously been denied permission to travel have been able to do so, including human rights defenders and independent bloggers. The travel reforms, however, gave the government broad discretionary power to restrict the right to travel on grounds of “defense and national security” or “other reasons of public interest,” and authorities have continued to selectively deny exit to people who express dissent without due process.

The government restricts the movement of citizens within Cuba through a 1997 law known as Decree 217, designed to limit migration from other provinces to Havana. The decree has been used to harass dissidents and prevent people from traveling to Havana to attend meetings.

In May 2019, journalist Luz Escobar, of the independent website 14yMedio, was barred from traveling to Miami. In August, she was barred from traveling to Argentina, and journalist Javier Valdés from the publication Convivencia, from traveling to Spain. Agents informed them only that they were not authorized to travel. Also in August, evangelical pastor Adrián del Sol was barred from traveling to Trinidad and Tobago, where he was scheduled to participate in an event on religious persecution.

Prison Conditions

Prisons are overcrowded. Prisoners are forced to work 12-hour days and are punished if they do not meet production quotas, according to former political prisoners. Inmates have no effective complaint mechanism to seek redress for abuses. Those who criticize the government or engage in hunger strikes and other forms of protest often endure extended solitary confinement, beatings, restriction of family visits, and denial of medical care.

While the government allowed select members of the foreign press to conduct controlled visits to a handful of prisons in 2013, it continues to deny international human rights groups and independent Cuban organizations access to its prisons.

Labor Rights

Despite updating its Labor Code in 2014, Cuba continues to violate conventions of the International Labour Organization that it ratified, regarding freedom of association and collective bargaining. While Cuban law technically allows the formation of independent unions, in practice Cuba only permits one confederation of state-controlled unions, the Workers’ Central Union of Cuba.

Human Rights Defenders

The Cuban government still refuses to recognize human rights monitoring as a legitimate activity and denies legal status to local human rights groups. Government authorities have harassed, assaulted, and imprisoned human rights defenders who attempt to document abuses. In July, Ricardo Fernández Izaguirre, a rights defender and journalist, was detained after leaving the Ladies in White headquarters in Havana, where he had been documenting violations of freedom of religion. He was released after nine days in prison.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Following public protest, the Cuban government decided to remove language from the draft of the new constitution approved in February 2018 that would have redefined marriage to include same-sex couples. However, transitory disposition No. 11 of the constitution mandates that within two years after approval, a new Family Code will be submitted to popular referendum “in which the manner in which to construct marriage must be included.”

In May, security forces cracked down on a protest in Havana promoting lesbian, gay, bisexual, ad transgender (LGBT) rights and detained several activists, media reported. The protest, which was not authorized, was organized after the government announced that it had canceled Cuba’s 2019 Gay Pride parade.

Key International Actors

In November 2017, the US government reinstated restrictions on Americans’ right to travel to Cuba and to do business with any entity tied to the Cuban military, or to Cuban security or intelligence services. In March 2019, the Trump administration opened up a month-long window in which US citizens could sue dozens of Cuban companies blacklisted by the US administration.

In June, the US administration imposed new restrictions on US citizens traveling to Cuba, banning cruise ship stops and group educational trips. The US Treasury Secretary said the restrictions are a result of Cuba continuing to “play a destabilizing role in the Western Hemisphere, providing a communist foothold in the region and propping up US adversaries in places like Venezuela and Nicaragua by fomenting instability, undermining the rule of law, and suppressing democratic processes.”

In March, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reiterated a request to the Cuban government to be allowed to visit the country to monitor the human rights situation.

In September, the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, visited Cuba to co-chair the second EU-Cuba Joint Council which discussed EU-Cuban relations, in particular in the EU-Cuba political dialogues as well as political and trade cooperation.

Cuba’s term as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council expired at the end of 2019. During its time on the council, Cuba regularly voted to prevent scrutiny of human rights violations, opposing resolutions addressing abuses in countries including Venezuela, Syria, Myanmar, Belarus, Burundi, Iran, and the Philippines.

The Mirage of Transition in Cuba

On April 19, Raúl Castro stepped down from his self‐ascribed title as president of Cuba and transferred the post to his deputy, Miguel Díaz‐Canel. For the first time since 1959, neither of the Castro brothers, Raúl or the late Fidel, supposedly rules the island. The handover of power to a new generation — Díaz‐Canel is 57 years old — and changes to some political rules, such as the introduction of term limits, have fueled hopes that in the midterm a democratic opening might be in the cards. However, this so‐called transition is just a mirage.

The Castro family remains firmly in control of the government and the military. Raúl has kept his posts as secretary general of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) and commander‐in‐chief of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR). Meanwhile, his son, Alejandro Castro Espín, is at the center of a new power structure that Raúl carefully put in place in recent years, one in which the military elite and the second tier of the Communist Party leadership are in charge.

Fifty‐two‐year‐old Castro Espín is currently a colonel in the Interior Ministry. He is the coordinator of the intelligence and counterintelligence services, which makes him one of the most powerful figures in Cuba. He was also the head of the National Defense and Security Commission, a recently disbanded advisory body to Raúl Castro that many perceived to be a “parallel government.” Rumor has it that Raúl’s goal is to place Castro Espín as secretary general of the PCC by 2021, which would make him the effective ruler of Cuba.1

Díaz‐Canel — although nominally the president — will not wield real power. He himself confirmed this in his inaugural speech to the National Assembly, in which he stated that “Raúl Castro Ruz, as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, will make the most important decisions for the present and the future of the nation.”2

The idea that a democratic transition is underway in Cuba is further belied by two well‐documented developments: the increased crackdown on dissidents and groups in civil society, and the regime’s backtracking on the timid economic policy changes Raúl Castro implemented when he came to power in 2006.

A GRIM OUTLOOK FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES

Despite the hopes stirred by the diplomatic rapprochement between Washington and Havana more than three years ago, it is now clear that the Cuban regime does not intend to change the fundamental nature of its Stalinist political system. In fact, there is evidence that the dictatorship has increased its repression of dissidents and civil society.

The number of arbitrary detentions for political reasons reached 9,940 in 2016, exceeding that of any previous year since 2010,3 and detentions have since remained high.4 Since Barack Obama visited the island in March 2016, the Cuban political police have made it even more difficult to demonstrate. Police officers are now placed outside the houses of dozens of activists during the weekends to prevent those activists from participating in the Sunday marches organized by the Damas de Blanco (Ladies in White) and #TodosMarchamos. The police also make it nearly impossible for other human rights defenders and political activists to meet. Hostility against the families of activists has increased as well. The number of political prisoners has doubled to 140 over the last couple of years.5

Even though in 2013 the regime lifted — although not entirely — the requirement for ordinary Cubans to get permission to travel abroad, democracy activists’ ability to travel is severely limited. Dozens of Cubans have been arrested by the security police days before traveling, on their way to the airport, or even at the airport, and have thus been prevented from participating in seminars and conferences abroad organized by international human rights organizations. Limits on travel to the island also persist for Cubans living abroad: individuals who have criticized the dictatorship or been politically active against it are not allowed to visit.

In April 2016, the PCC gathered for its Seventh Congress. In his opening speech, Raúl Castro made it clear that there would be no reforms that could threaten the “unity of the majority of the people behind the Party” or “cause instability and insecurity.”6 Referring to international demands for a multiparty system, Castro clarified that such a system would occur “neither today, nor ever” and warned that “if one day they succeed in fragmenting us, it would be the beginning of the end of our fatherland, of the Revolution, socialism, and national independence.” Foreign minister Bruno Rodríguez claimed in his speech that Barack Obama’s visit had been “an attack on our conception, on our history, on our culture, and on our symbols.”7

The objective of the PCC’s Seventh Congress was to discuss two documents. The first describes the principles and theories of the economic and social model of the Cuban government. It states that the PCC is “the superior leading force of the society and the State.”8 The second document outlines the “Vision of the Nation” for 2030. Cuba should be “sovereign, independent, socialist, democratic, prosperous, and sustainable,” and to achieve this, the document deems it necessary to have an “efficient and socialist government.”9

Two guiding principles of that vision — national defense against aggression and national security — reinforce the regime’s current defense doctrine, which states that the regime’s institutions, political and mass organizations, and the rest of the population will participate in confronting the activities of “the enemy.” The militarization of society and the inclusion of ordinary citizens in the surveillance system have been two of the most effective strategies to curb self‐organizing in Cuban civil society.

There is scant mention of reform in those documents. Freedom of expression or assembly or multiparty democracy cannot be part of the regime’s narrative. When the PCC declares those principles and that vision for the coming 15 years, it does not have in mind anything other than continuing in exactly the same way as it has for the last six decades.

The only reform within the political system announced at the PCC Seventh Congress concerned the age of individuals entering the highest positions of the party — the central committee, the secretariat, and the political bureau — and how long they will be allowed to hold their positions. In the future, nobody above the age of 60 will enter those bodies or serve for more than two five‐year terms. With this amendment, Raúl Castro wanted to rejuvenate the apparatus and create a new network of loyalists for his son and inheritor, Alejandro. Castro also promised that those changes would be included in the constitution and proposed a constitutional reform and subsequent referendum, a process that would “ratify the irrevocable nature of the political and social system.”10

BACKTRACKING ON TIMID POLICY CHANGES

The consolidation of power in the hands of the Castro family does not seem to be the main topic of concern for most Cuba watchers. Instead, they focus on the promise of the economic program adopted by the PCC in 2011, aimed at creating a small‐business sector that could generate employment and improve services. Unfortunately, those policies have been too timid to bring about meaningful change to the Cuban economy, and the regime is now backtracking on some of them.

The number of independent microbusinesses grew rapidly between 2010 and 2014, but that growth has significantly decelerated since.11 In recent months, the regime has announced new restrictions on the private sector because of complaints about, among other things, “excess accumulation of wealth.”12 It also stopped handing out licenses for small businesses, saying it needs to reevaluate the legal framework around these businesses and combat corruption related to them. In July 2017, Raúl Castro openly criticized the dynamics of the microbusinesses. A leaked video recently showed Díaz‐Canel saying that the regime sees entrepreneurs as capitalist instruments who can destroy the revolution. As The Economist’s Bello column rightly points out, “the government wants a market economy without capitalists or businesses that thrive and grow.”13

The regime continues to exert absolute control over the legal labor market, retaining — or confiscating — around 95 percent of the hard‐currency earnings of all Cubans working in the formal dollar economy.14 These profits are then invested in the state’s repressive machinery and in the personal coffers of the Communist Party leadership. This modern‐day system of slavery will not lead to the empowerment of Cuban workers or to the advancement of their rights.

Moreover, the concentration of economic power in the hands of the FAR has accelerated since 2014. The FAR own at least 57 companies and half of the retail businesses in Cuba, along with car fleets, gas stations, and supermarkets — all of which are key sectors of the economy.15 They also control at least 40 percent of the foreign capital in the country through their holding company, Grupo de Administración Empresarial Sociedad Anónima (GAESA). This means that foreign investors in Cuba must establish direct relations with GAESA and its CEO, Luis Alberto Rodríguez López‐Callejas, Raúl Castro’s son‐in‐law.

PROSPECTS FOR CHANGE

The lack of human rights and democracy is the essence of Cuba’s totalitarian political and economic system. The legacy of the Castro brothers includes not only executions, imprisonments, assassinations, torture, beatings, harassment, and intimidation but also a constitutional and legal framework that legalizes repression and promotes widespread violations of human rights by the authorities.

It is not realistic to expect that the Cuban regime will embrace democracy and the rule of law any time soon. A real transition in Cuba must involve the immediate release of political prisoners, the restitution of all fundamental rights and freedoms, the complete dismantling of the dictatorship, and the celebration of free, multiparty, and competitive elections — in other words, the construction of a functioning democracy.

NOTES

1 Roberto Álvarez Quiñonez, “¿Necesita Alejandro Castro, el hijo consentido, ser presidente?” Diario Las Américas, January 22, 2018, https://www.diariolasamericas.com/america-latina/necesitaalejandro-castro-el-hijo-consentido-ser-presidente-n4141838.

2 “Primer discurso completo de Díaz‐Canel como presidente de Cuba,” Pulso de los Pueblos, April 19, 2018, http://pulsodelospueblos.com/primer-discurso-completo-de-diaz-canel-como-presidentede-cuba/.

3 Deutsche Welle, “Cuba Arbitrary Arrests Soared in 2016, Dissidents Say,” January 6, 2017, http://www.dw.com/en/cubaarbitrary-arrests-soared-in-2016-dissidents-say/a-37033489.

4 Data f rom Defenders’ Databas e, https://database.civilrightsdefenders.org/.

5 Figures from the Cuban Commission on Human Rights and National Reconciliation (CCDHRN), http://ccdhrn.org/.

6 Raúl Castro Ruz, “Informe Central al VII Congreso del Partido Comunista Cuba,” Cuba Debate, April 17, 2016, http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2016/04/17/informe-centralal-vii-congreso-del-partido-comunista-cuba/#.Wt9DkBPwZhE.

7 “Raúl Castro y canciller cubano arremeten contra visita de Obama,” CBS News, April 18, 2016, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/raul-castro-y-canciller-cubano-arremeten-contra-visita-de-obama/.

8 See “Documentos del 7mo. Congreso del Partido aprobados por el III Pleno del Comité Central del PCC el 18 de mayo de 2017 y respaldados por la Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular el 1 de junio de 2017,” http://www.granma.cu/file/pdf/gaceta/%C3%BAltimo%20PDF%2032.pdf.

9 “Documentos del 7mo. Congreso del Partido aprobados por el III Pleno del Comité Central del PCC el 18 de mayo de 2017 y respaldados por la Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular el 1 de junio de 2017.”

10 Article 5 of the Cuban Constitution already states that “The Communist Party of Cuba . . . is the highest leading force of society and of the state, which organizes and guides the common effort toward the goals of the construction of socialism and the progress toward a communist society.”

11 Redacción, “Licencias para trabajo privado en Cuba: las que sí, las que no,” On Cuba, August 3, 2017, https://oncubamagazine. com/economia‐negocios/licencias‐trabajo‐privado‐cuba‐las‐quesi‐las‐que‐no/.

12 Reuters, “Cuba Tightens Regulations on Nascent Private Sector,” December 21, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cuba-economy/cuba-tightens-regulations-on-nascent-privatesector-idUSKBN1EF318.

13 Bello, “A Year Without Fidel.” The Economist, December 9, 2017, p. 38.

14 “Testimony of the International Group for Corporate Social Responsibility in Cuba before the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights,” October 15, 2005, p. 17, http://www.cubastudygroup.org/index.cfm/files/serve?File_id=5411e1c1-7883–4015-9d22-2d0ecc99318b.

15 Michael Smith, “Want toMarkets Do Business in Cuba? Prepare to Partner with the General.” Bloomberg Markets, September 30, 2015, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2015–09-30/want-toinvest-in-cuba-meet-your-partner-castro-s-son-in-law.

On April 2018, Miguel Díaz-Canel became Cuba’s new president after six decades of oppressive rule by the Castro family, but it is still politics as usual on the island.

According to BBC News, Díaz-Canel became president in a handover by Raul Castro. There was no real participation from the Cuban people in the election process. The new president has already promised to preserve the island’s one-party system and Raul Castro remains in control of the government’s direction as the leader of Cuba’s Communist Party.

It is clear that the government in Cuba will continue being a dictatorship as it has been under the Castro brothers. Let’s take a closer look at how Cuba’s current system contrasts a democracy.

Cuba’s “Electoral” Process

The Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) considers itself to be a “democracy of the people” but it has nothing to do with democracy because it gives the Cuban people no real choices in electing their leaders. The PCC outlaws any other political party. Anyone running for office must be part of the Communist Party and the electoral process is intentionally murky.

Cuba’s president is supposedly chosen by the National Assembly, whose members are selected by government-designated commissions and vetted by top leadership. All the public can do in the process of nominating National Assembly members is to vote to approve or reject the candidates that have already been pre-selected.

NBC News explains that it is no coincidence that each one usually “receives” at least a 95 percent approval rate. This process is a thinly veiled sham since the National Assembly just does whatever the island’s executive power wants.

According to the Chicago Tribune, the assembly approves all executive branch proposals by margins of 95 percent or more. For example, in this last election for president, it is widely known that Miguel Díaz-Canel was Raul Castro’s clear choice for a successor and the National Assembly just went along with his choice.

Diversity of Political Ideas and Representation

There is no room for diversity of political ideas in Cuba’s one-party system.Therefore, there is no real way for people to make informed decisions – even when voting on a basic level.

Cuba’s Communist Party is the only legal party on the island. As such, any other group seeking to assemble independently is considered illegal and punished with violence or imprisonment.

Civil Liberties for Citizens

Cubans are not afforded the most basic civil liberties. All media is controlled by the government and therefore only report Communist propaganda. Cuba’s press does not serve as a check on the government’s power.

Any websites or blogs critical of the government are routinely blocked or shut

down. Internet access is more than seven times more expensive than in the U.S. and 25 times pricier in Haiti. It’s of bad quality, and still not easily accessible to the Cuban people, even after some hundreds of public hotspots were installed throughout the island. Connections remain spotty and incredibly slow.

Limiting the right to gather and assemble is also one of the main ways the government controls Cuban citizens. Security officers and paramilitary thugs are known to routinely break up peaceful protests or gatherings of anyone known to be in opposition. Neighbors are also encouraged to spy on one another and to report any suspected behavior against the state.

Even freedom of religion faces its obstacles on the island. Churches face constant pressure from the government. In 2018, certain Christian churches on the island were pressured by the Communist Party to persuade members to vote “yes” on the referendum for a new constitution being pushed by the Communist regime. Clearly, there are no boundaries the government in Cuba will not cross in order to continue oppressing its people.

Effectiveness of the Rule of Law

The Cuban people cannot rely on their court system to uphold laws and protect them. They cannot benefit from fair and public hearings or to be tried by an impartial jury of their peers.

The Council of State controls all of the courts in Cuba and their decisions always align with the interests of the Communist Party. Cuba’s people cannot count on due process. Dissidents can expect to be prosecuted under vague charges such as disrespecting authority and creating public disorder. The so-called “dangerousness laws” allow authorities to send any person to jail to 4 years even when no crime was committed.

Cuba’s prisons are also known to be crowded, contain poor sanitation, and use forced labor. Torture committed by guards is common practice. Prisoners are punished if they do not meet strict work quotas. Nothing about Cuba’s laws and how they are enforced is fair or helpful thanks to the Communist government.

Those who denounce the government or take part in hunger strikes and other protests often must face extended solitary confinement, are denied medical care, denied family visits and are subject to violent actions.

Self-Determination and Individual Rights

Lastly, a Cuban’s right to choose how they live their personal lives is also closely restricted. Even the art they purchase or have commissioned must be approved by the government first. President Díaz-Canel signed Decree 349 in April 2018, which established far-reaching and vague restrictions on artistic expression.

Under the regulation, Cuban citizens who hire artists for creative services without proper authorization are subject to sanctions and punishments. Both the buyer and commissioned artist face punishment under this draconian order.

Under present regulations, Cuban citizens who hire artists to provide private services without authorization are subject to sanctions and punishments, including the instruments of the artists and even the homes of the persons involved.

While some restrictions on starting small businesses were lifted in December 2018, this was just a smokescreen for more control over new companies. Longer waits for authorization, more bureaucratic procedures, and increased government controls have essentially stalled small businesses from actually being able to take off meaningfully for Cuban entrepreneurs.

The ability for Cubans to move and work where they please is also severely restricted. A citizen seeking to move to another town or city must first seek government permission or risk being sent back to their place of origin.

A long list of thousands of Cuban citizens are also blacklisted by immigration and prevented to freely visit the country where they were born.

Castro and Communism in Cuba

Meanwhile, an example of communist tactics was being unfolded in Cuba, within 90 miles of the U.S. southeastern shoreline. Early in 1959, after battling for several years,

Fulgencio Batista. Mindful of Batista's cruel record of repression, the U.S. government and the American public in general welcomed Castro's rise to power as a victory for democracy.

American sympathy rapidly evaporated, however, when Premier Castro began to act and sound like a communist dictator. He failed to hold the free elections he had promised the Cuban people. He put to death hundreds of his former political enemies in hasty trials intended more as propaganda than as judicial proceedings. Then he proceeded to fill Cuba's jails once more with political critics, including many of Castro's former comrades, anti-communist labor leaders, and other veteran opponents of the Batista regime. The press was placed under strict censorship. Foreign-owned property was expropriated arbitrarily without fair compensation, and in many cases without any compensation at all. Only the communists emerged unscathed from Castro's repressive and vindictive actions.

As his internal dictatorship hardened, Castro began increasingly to denounce the United States and to seek support from the communist bloc nations. In the face of rising provocations, the Eisenhower administration at first adopted a policy of patient waiting. During the summer of 1960, however, American policy stiffened. The United States placed a temporary embargo on the purchase of Cuban sugar and urged the 21-nation Organization of American States (OAS) to condemn Cuba's actions. The OAS, while it did not directly criticize the Castro regime on this occasion, did condemn communist interference in the Western Hemisphere.

Another international gathering, held later in 1960, seemed to sum up the hopeful and disturbing aspects of the world scene. Meeting in New York, the U.N. General Assembly admitted 16 new nations, all but one from the African continent, a reflection of the rapid postwar movement of formerly colonial peoples to full independence and nationhood. In a speech to the U.N. delegates, President Eisenhower asked other nations to join the United States in providing increased aid to developing areas generally and to the new African nations in particular. He also pledged that the United States would continue to seek a workable program of world disarmament based on an effective system of inspection and control.

Prior to the General Assembly session, world concern over the mounting arms race had been heightened by man's conquest of space, a development which in more tranquil times would have been a source only of admiration and pride. The launching of the first Soviet space satellite in October 1957, and the first American satellite in January 1958-followed by many others-demonstrated that both countries now had rockets powerful enough to hurl atomic and hydrogen bombs into the heart of an enemy country thousands of miles away. In the absence of a foolproof arms inspection system, there was always the danger that, accidentally or otherwise, a push-button war might break out which could destroy millions of lives in a single blinding instant. World opinion was therefore shocked and disheartened when Premier Khrushchev told the U.N. General Assembly in belligerent tones that the Soviet Union would not accept inspection and control in the initial stages of a disarmament agreement. Soviet leaders knew that disarmament without inspection was unacceptable to the democratic nations, since it would give dangerous advantage to a closed society like the Soviet Union which could violate its disarmament pledges with little chance of being found out, whereas violations within a democracy would have a high chance of being discovered and publicized.

What Is Cuba’s Post-Castro Future?

Miguel Diaz-Canel, set to replace Raul Castro as president of Cuba after sixty years of Castro rule, will be faced with the challenges of implementing economic reform and sidestepping regional isolation.

April 18, 2018

8:00 am (EST)

The departure of Raul Castro this month as president of Cuba will mark the first time in sixty years that the country will not be ruled by someone with the surname Castro. While Raul carried out some incremental reforms, the legacy of Raul and his brother Fidel is one of a long-repressed, economically stunted nation, says Christopher Sabatini, lecturer of international relations at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and executive director of Global Americans. Though Castroism is expected to continue under apparent successor First Vice President Miguel Diaz-Canel, he represents generational change and is likely to have more contact with Cubans as well as foreign leaders, says Sabatini.

How will Raul’s presidency be remembered?

Raul will be seen as a continuation of the Fidel Castro government; with Fidel or Raul having governed since 1959, it’s clearly a family affair. But his time in power will also be remembered as one of marginal, incremental reforms.

More on:

When Raul took power, he said that the Cuban economy was a failure—something you never would have heard the infamously obstreperous Fidel say. Raul implemented a series of reforms intended to create market incentives in the Cuban economy: he allowed some measures of private enterprise, rewrote the laws for investment, welcomed Brazilian investment in the Mariel Port, and even allowed some forms of private farming to address national food shortages. His saying was: “Without pause, but without haste.” In other words, he would move the country forward but at his own pace.

But Cuba under the Castros—Fidel and Raul—was still a dictatorship. It’s been a totalitarian state since 1959. There are no democratic elections. Cubans are not allowed to congregate freely and are limited in their freedom of expression and access to information. There’s only one official newspaper run by the Communist Party, and it consists almost entirely of propaganda to support the party and its policies. The result is that Cubans have become atomized.

Explain how the upcoming selection of new leaders will work.

It’s a parliamentary style system. The first round of elections was held in October, when delegates were elected to local councils. Local delegates, together with some national figures and associations such as the ruling Communist Party, then selected provincial delegates from their own ranks. From these were chosen delegates to the National Assembly. All that is left is for the National Assembly to select a Committee of Candidates, from which the next president, the first and second vice presidents, and the Council of State—the group of politicians who meet weekly to review national policy orientation and implementation—will be chosen come April 19.

But the process isn’t democratic. Only members of the Communist Party are allowed to run. People are only voting from an official, pre-approved slate of candidates. There’s choice, but only within the system. And during the first round of elections at the level of local council, voting was held in the open, with no secret ballot process.

All signs point to Diaz-Canel being sworn in as president. What do we know about him?

Diaz-Canel is fifty-seven—relatively young to those who govern today. The average age of the Council of State is now well over sixty years old. He’s the only candidate who was not born during the [Cuban] Revolution. He’s truly a new generation. He’s known to like rock and roll, and is also known to be modest. He used to ride his bicycle to work, and even in these recent elections he waited in line to cast his ballot just like everyone else. He’s kept his head low.

Diaz-Canel rose through the party itself; he started as a provincial secretary in Santa Clara. He’s been groomed from the beginning. If you speak to the average Cuban, they’ll try to tell you that the election is uncertain and that someone other than Diaz-Canel could be elected, but this is meant to build a facade of a more democratic process rather than a coronation, which is effectively what this election is. Choosing someone else would be more than just breaking with the name of the Castros. It would be an apparent break with the will of the Castros. I don’t expect that to happen.

What might this regime change mean for the average Cuban?

There’s a fair amount of expectation. Most Cubans have waited for a long time for some sort of response to their demands for an end to the Castros. By virtue of his age and provincial background, Diaz-Canel is very aware of these frustrations and will likely be much more in contact with the people.

But Diaz-Canel will also continue to be surrounded by people who are very committed to Castroism. Raul Castro is going to continue as the secretary-general of the Communist Party and will remain the de facto head of the armed forces. His son, Alejandro, will remain the de facto liaison between the military, intelligence, and civilian sectors. The thing to keep an eye on is how many of the older generation—the former revolutionaries—get elected to the Council of State. Diaz-Canel will have a little more of a free hand if people of his generation and people of his choosing dominate that council.

Having said that, Diaz-Canel is faced with some very serious challenges. The first is currency unification. There are two currencies in Cuba, which create huge distortions in the economy and act as disincentives to foreign investment. [The Cuban convertible peso (CUC), pegged to the U.S. dollar and used in the tourism industry and to price consumer goods, is worth twenty-five times more than the Cuban peso (CUP), used largely by locals.] Unification could be a very wrenching process, and could even risk inflation and a higher cost of living. The second is, of course, finding ways to generate hard currency. The third is tax collection, and the large number of cuentapropistas [self-employed persons] who make up the informal sector and evade taxation. Diaz-Canel will have to show very strong leadership, but always in the context of the revolution.

How might the upcoming political turnover affect U.S.-Cuba relations?

I do not expect any changes under the Trump administration, whose policy toward Cuba is being guided by a desire to isolate and coerce changes from the government. The Cuban government does not take kindly to coercion.