JANUARY 2021 - HUMAN RIGTHS - 1000 COPIES

Artists in Cuba Spearhead First Mayor Protest in Decades

A 27N meeting at the Institute of Artivismo (INSTAR) in Havana. (Reynier Leyva-Novo)

In the middle of the night on November 28, 32 Cuban artists emerged from a five-hour meeting with officials of the Ministry of Culture. They had called on the Cuban government to refrain from harassing independent artists, to stop treating dissent as a crime, and to cease its violence against the San Isidro Movement, a group of artists and activists that had staged a hunger strike to protest the arrest and sentencing of a young rapper. The news of the encounter was shared with a crowd of about 300 artists, writers, actors, and filmmakers who had stood outside for more than 12 hours to pressure ministers to open their doors. Nothing like this had ever happened before on the island.

Cubans may complain about food shortages and other restrictions on their lives, but members of elite professions rarely stick their necks out to defend anyone that the state labels a dissident. It is unheard of to exhort Cuban officials to listen to their most vocal critics in person. Although the artists of the San Isidro Movement were known to many, harassment of the group had not generated a major outcry. But in the past three years the Cuban government has issued laws imposing restrictions on independent art, music, filmmaking, and journalism, incurring the anger of many creators. When they saw live streamed videos of the weakened hunger strikers being attacked by security agents disguised as health workers, they decided that enough was enough.

“This is the first time that artists and intellectuals in Cuba are challenging the constitution,” said Cuban historian Rafael Rojas in a radio broadcast. “Their emphasis on freedom of expression and association challenges the legal, constitutional, and institutional limits of the Cuban political system.” In an interview with journalist Jorge Ramos, artist Tania Bruguera said the uprising started because, “a group of Cuban artists have gotten tired of putting up with being abused, harassed, and pursued by police because of their political views and for their independence from state institutions.”

Within 48 hours, the Cuban government began to renege on verbal promises made at the meeting not to harass the protestors.Within 48 hours, the Cuban government began to renege on verbal promises made at the meeting not to harass the protestors. President Diaz-Canel, Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez, Minister of Culture Alpidio Alonso, and Casa de las Americas director Abel Prieto all tweeted defamatory statements about the protesters Cuban state television aired several programs lambasting the San Isidro Movement, Tania Bruguera, and journalist Carlos Manuel Alvarez as mercenaries paid by the U.S. to destabilize the revolution. Bruguera and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara were threatened by state security and detained for walking outside. Police blocked off and guarded the street where the Ministry of Culture is located. Several activists and independent journalists were placed under house arrest. Police shut down the headquarters of INSTAR, Tania Bruguera’s International Institute of Artivism. The San Isidro Movement was accused on Cuban television of breaking the windows of a hard currency store, but it was soon revealed that the man who committed the act was an agent provocateur working for Cuban police.

The protests come at a moment when the Cuban government has been shaken by the colossal loss of tourism revenue during the pandemic, the dwindling support from Venezuela, and the tightening of the U.S. trade embargo during the Trump years. It was a sign of weakness that officials ceded to the demand for a face-to-face encounter with protesters.

But the state’s reaction is not surprising. Cultural Ministry officials are expected to respond to the demands of the Communist Party and State Security, not to citizens organized outside state sanctioned organizations. The slanderous campaigns on state television and social media are intimidation tactics aimed at preventing more Cubans from rising up. And it is also not unusual for the Cuban government to clamp down on dissent during economic downturns, as happened after the failed 10-million-ton harvest in 1971 and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

What is extraordinary is that young Cuban intellectuals and artists have chosen to air their grievances publicly and collectively, and to support each other regardless of divergent political opinions.What is extraordinary is that young Cuban intellectuals and artists have chosen to air their grievances publicly and collectively, and to support each other regardless of divergent political opinions. They have not been seduced by promises of favorable treatment from the state in exchange for silence, nor are they succumbing to the self-doubt that police states are so adept at inculcating in the citizenry. Most importantly, despite persistent police harassment, they are not giving up. They have adopted a name–27N–in commemoration of the day they first came together. A few members of the San Isidro Movement are part of 27N, but the group also includes representatives of other cultural fields that participated in the mass protest. 27N has formed subcommittees to attend to various tasks, from media relations to visual documentation to legal consultations.

27N continues to prepare for the next session with officials. They

posted an initial list of demands in an online petition: political

freedom for all Cubans, the release of the rapper Denis Solís, the

cessation of state repression of artists and journalists who think

differently, the cessation of defamatory media campaigns against

independent artists, journalists and activists because of their

political views, and the right to and respect for independence. On

November 27, Cuban, officials promised a second meeting, but on December

4 the Ministry of Culture terminated the dialogue

due to an “insolent” email from the protesters, who had requested to

have a lawyer present and asked that harassment against them cease.

Instead, the Ministry convened a meeting with small group of artists

that were deemed to be loyal to the revolution.

A 27N meeting at the Institute of Artivismo (INSTAR) in Havana. (Reynier Leyva-Novo)

The retreat may have been a result of orders from higher ranking officials as famous Cuban folk singer Silvio Rodriguez suggested. Rodriguez, considered by many to be an apologist for the regime, nonetheless understands that the officials in the cultural ministry were engaging in a defensive, though morally illegitimate, political move.

It is not surprising that prominent but independently minded Cuban artists and intellectuals such as singers Carlos Varela and Haydee Milanés have voiced support for the protestors. But it was nothing short of astonishing that the regional chapters of the Union of Cuban Artists and Writers (La Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba, UNEAC) and the Hermanos Saíz Brigade on the Island of Pines posted a message of solidarity with the San Isidro Movement on December 7 on Facebook, decrying the Cuban government’s defamatory campaigns, writing on Facebook, “We will not advance toward a dialogue and mutual respect by resorting to dismissive insults.” Cuba’s political culture does not embrace public expressions of dissent within its ranks, nor do regional representatives of organization tend to speak out about activities in the capital.

For the young Cubans who rose up in rebellion, their smartphones are weapons they use both to inform and defend themselves.Changes in Cuban culture played a significant role in the November 27 protest. For the young Cubans who rose up in rebellion, their smartphones are weapons they use both to inform and defend themselves. The legalization of cell phone possession in 2008 and the opening of phone-based internet access in 2018 utterly transformed Cuban public discourse. Young Cubans use Facebook as an alternative public sphere in which to share news, air grievances, galvanize support for causes, and cast aspersions on their leaders. Official state media has been upstaged. Cuba’s leaders are being thrust into arguments with disgruntled citizens on social media – and their responses are undignified to say the least. The Cuban government tries to block access to opposition media, but young Cubans fight back with VPN networks and mirror sites. In her daily podcast, Yoani Sánchez explains to listeners how to use a VPN. Dozens of independent journalism publications and streaming channels have blossomed on the internet, providing Cubans with news and views that would never appear in state media.

Communication between Cuban exiles and islanders is fluid and constant, signaling a complete breakdown of the state’s effort to drive a wedge between those inside and outside the country. Cubans have grown more emboldened by being able to see what others like them do and by witnessing what the state does to other Cubans. WhatsApp chats facilitate the creation of organizations based on special interests, including Cuban doctors on medical missions who share information about the oppressive labor conditions and constant surveillance they experience. The island now has independent animal rights groups, LGBTQ groups, feminist groups, and anti-racist groups, all of which have organized smaller protests in recent years using social media.

Cubans do not need the United States to “help” them develop critical views of their government.The Cuban government continues to dismiss all forms of dissent on the island as the works of mercenaries trained, financed, and mobilized by the United States government as part of a long-term regime change strategy. More than a few progressives outside Cuba parrot that rhetoric or at least feel obligated to prioritize their condemnation of U.S. policies over concerns about Cubans’ civil rights. Many Cubans and Cuban-Americans, myself included, would argue that it is a mistake to rationalize or diminish the Cuban government’s repression of civil liberties and blame the embargo for the government’s stance toward its citizens. While USAID has awarded $16,569,889 for Cuba pro-democracy efforts since 2017, including financing of some of the opposition media, not all Cuban media beyond the island government’s control was invented by the CIA, nor is all Cubans’ opposition to their government a product of American meddling. Cubans do not need the United States to “help” them develop critical views of their government. “Anger rather than fear is the widespread sentiment among Cubans—a constant, built-in discomfort,” writes Carlos Manuel Alvarez. “We’re fed up with blind, doctrinaire zeal. Navigating Communism is like trying to cross a cobblestone road in high heels, trying not to fall, feigning normalcy. Some of us end up twisting our ankles.”

Most complaints of police repression, domestic violence, animal mistreatment, food shortages, and poor public services in Cuba come from ordinary Cuban citizens who post their grievances on Facebook. No American planes are dropping leaflets from the sky to provide instructions. Cuban exiles send billions of dollars to relatives and friends each year, and much of that money pays for cell phones, internet, computers, and other tech equipment that allow islanders to send and receive information. Important opposition media outlets, such as 14yMedio and CiberCuba, are entirely privately financed. Tania Bruguera and Yoani Sanchez have made a point of not accepting any funding from the U.S. government, and savvy musicians and filmmakers use crowd funding campaigns to support their projects. The bulk of U.S. State Department funding for Cuba-related activities stays in Miami, where media companies, publishers, and cultural promoters can operate freely.

Cuban citizens may have limited legal rights, but they do not lack agency; they choose to apply for foreign grants or to work for media outlets funded by American sources. I do not make these points because I favor U.S.-backed regime change–I am arguing for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics that are leading to more frequent, more visible, and more organized protests in Cuba. I am also arguing against the Cuban government’s position that does not differentiate between a CIA-financed assassin and an independent journalist who writes a brilliant essay about Cuba’s public health system, or an artist who recites poetry outside a police station.

The recent confrontation at the Ministry of Culture raised the hopes of many Cubans around the world. It also generated skepticism from those who say that dialogue with the Cuban government is futile, and that artists don’t have the knowhow to bring about political change. It’s worth recalling that the Charter 77 civic movement in the former Czechoslovakia started in response to the arrest of a psychedelic rock band. The myth of Cuba as a political utopia is the revolution’s jugular: it draws tourist dollars and foreign aid, but its claim to truth is undermined by the harsh lived realities of 11 million citizens. Cuban artists and intellectuals have been enjoined to sustain that myth for 60 years. Their collective refusal to do now is a clear sign that change is on the horizon.

Coco Fusco is an artist and writer and the author of Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba (Tate Publications, 2015). She is a professor at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

Cuba cracks down on artists who demanded creative freedoms after ‘unprecedented’ government negotiations

Cuban artists and intellectuals want more rights – and, in an unusual show of dissent, they demanded the government sit down with them to negotiate.

At 10:45 a.m. on Nov. 27, about 300 people gathered outside the Ministry of Culture in Havana to demand freedom of expression, an end to police harassment and the right to make art that Cuba’s communist government disagrees with. They organized the meetup on WhatsApp, a globally ubiquitous smartphone app used in Cuba only since 2018, with the arrival of mobile internet.

“I believe we were all convinced that we had to do something, and do it publicly and categorically,” the filmmaker Raúl Pardo, who helped organize the protest, said via Facebook message. “Each one of us sent messages to various people, we created a WhatsApp [chat], convened [the group] and explained what we were going to do.”

After hours of waiting, shouting and clapping, 30 of the artists managed to speak with Vice Minister of Culture Fernando Rojas.

The negotiations would end soon after they began, followed by a major crackdown on dissent. But the size, duration and public nature of the artists’ opposition, which continues today, are unprecedented – a sign of how resistance in Cuba has grown and changed in recent years.

Opposition then and now

Since the beginning of Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution, opposition on the island has basically had one strategy – confrontation – and one goal – ending the political system he founded.

Many Cuban dissidents have been quietly financed by the United States government, which promotes regime change in Cuba, and are warmly received in Washington by Cuban American politicians like Sen. Marco Rubio and Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart.

This relationship with the United States has undermined the legitimacy of the Cuban opposition, not only with the Cuban government but also with the Cuban people. Polling shows Cubans reject U.S. involvement in their internal affairs, including the six-decade-old Cuban economic embargo.

The Nov. 27 protests were homegrown – a result of Cuba’s recent economic liberalization and changing social dynamics, not American interference.

In 2009, Fidel Castro’s brother Raúl Castro passed a series of economic reforms that, among other changes, made it possible for people to run small businesses. Galleries and theaters opened in homes and other private spaces across Cuba, enabling artists to create and show their work outside of state-run channels.

Dissident artists took advantage of this newfound freedom to advance their political demands, leading the government in 2018 to publish a decree seeking to regulate independent artistic production and limit where artists can perform.

A different dissent

Rather than remain silent about repression, as they have on so many other occasions, Cuban artists have taken to the streets.

The Nov. 27 protest at the Ministry of Culture came in response to a Nov. 26 government raid on the home of Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, leader of the San Isidro Movement, an artist collective that opposes the 2018 decree. Alcántara had been on a hunger strike to protest the detention of Cuban rapper Denis Solís for “insulting” a police officer.

Both Solís and Alcántara are vocal critics of the Cuban government, which they call a “dictatorship.”

Such language has led to accusations that the San Isidro Movement is a U.S.-funded operation. On Dec. 11, a news program on state television ran a video of a San Isidro Movement member calling for a U.S. military intervention in Cuba.

On Nov. 24, just before the artist protests, the U.S. State Department released US$1 million dedicated to increasing civil, political and religious rights in Cuba. It is unclear whether U.S.-financed groups are funneling money to the San Isidro Movement, according to the Cuba Money Project, which reports on American programs and projects related to Cuba.

In any case, while the raid on San Isidro sparked the Nov. 27 protest, only a few members of the movement were present in the crowd that gathered outside the Ministry of Culture. These protesters had broadly artistic, rather than explicitly political, demands and sought to work with – not against – the government to achieve them.

For “a group of contrary artists … to sit and talk with an institution that has never wanted to recognize their existence. That is a historic and unique act,” one participant told OnCuba News on Dec. 8.

Broken dialogue

If the events of Nov. 27 were novel, the government’s response was familiar.

On Nov. 28, after he met with the protesting artists, Vice Minister Rojas was interviewed for a TV special on a Cuban state-run channel. In it, he recounted the events of the protest day and reiterated the Ministry of Culture’s willingness to continue the “dialogue” in a second meeting.

The remainder of the program, however, cast the San Isidro Movement in a negative light, calling its members “mercenaries” in an apparent effort to discredit the street protest. No protesters were invited to talk on the show.

A week later, on Dec. 4, the Cuban Ministry of Culture announced that the dialogue with protesters had been “ended by the people who asked for it.” The post blamed the protesters for putting unreasonable conditions on a second meeting, including the presence of Cuba’s president, Miguel Díaz-Canel, and of independent media.

For journalist Jorge Fernandez, however, the “dialogue was already dynamited” by the TV hit job.

Beyond San Isidro

Since negotiations ended, house arrests and arbitrary detentions of Cuban artists have both increased.

But so have demands for change.

A document published on Nov. 28 and signed by more than 500 intellectuals, artists, filmmakers and others reiterates the protesters’ original request – no more police harassment – and adds to the list of demands nothing less than political pluralism and the rule of law.

Such reforms, they say, are necessary for “the conservation of national sovereignty, independence and the integrity of the fatherland” – language seemingly chosen to demonstrate that their dissent has nothing to do with the United States. It’s opposition by and for the Cuban people.

The Cuban government continues to accuse anyone who sides with the dissenting artists of being “paid by U.S. agencies.”

“Since the beginning, the revolution has been the object of foreign interference,” says the filmmaker Ernesto Daranas. “But putting every criticism in that same bucket is now isolating [Cuba’s government] from reality.”

Hunger Strike in Havana Sparks a New Level of Protest for Cuban Artists

Young artists protest in front of the doors of the Ministry of Culture, in Havana, Cuba, Friday, November 27, 2020. Dozens of Cuban artists demonstrated in front of the Ministry of Culture in Havana on Friday night, protesting against the police evicting a group who participated in a hunger strike. (AP Photo / Ismael Francisco)

The arrest and subsequent eight month sentence of Cuban rapper and activist Denis Solís González has set off an escalating protest movement in Havana and abroad.

Solís was convicted of contempt on November 9 after he spoke out on Facebook about an incident where a Cuban police officer illegally entered his home. His expedited trial sparked a hunger strike that has rapidly gained international attention and marks a new level of opposition to the Cuban government from the artist community.

Members of the artist-activist group El Movimiento San Isidro (MSI) initially took to the streets in solidarity of their friend. They staged poetry readings and marches to peacefully protest the repression of free speech by Cuban authorities. Following days of demonstrations —in which many MSI members were arrested and locked up for short periods of time— the group took a more dramatic approach to civil disobedience.

On November 18, 15 members of the group locked themselves in the MSI headquarters in Old Havana and six began a hunger strike. Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara —one of the founding members of the group and the protest— refused water as well.

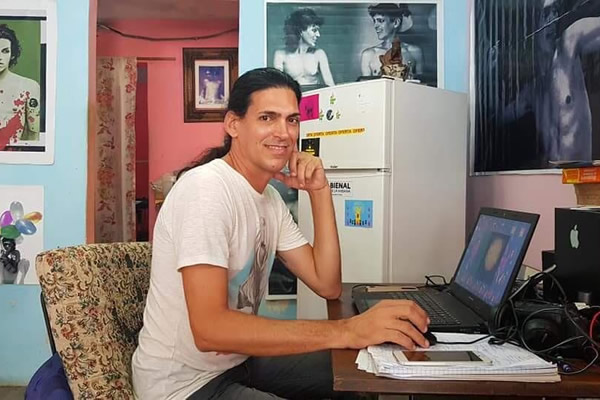

Michel Matos, a member of MSI, said the protesters had an absolute conviction to die if it showed the world the intolerance and injustice of the Cuban government. He did not take part in the hunger strike, but was initially providing statements from his home in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana. He said that if he left his home, he would be arrested by the police who had stationed themselves outside.

“They [Cuban authorities] are giving us no choice for a logical or positive solution,” Matos said. “The solution is that Luis will probably die. He is not going to die from his health but from his conviction.”

Supporters have used Facebook, YouTube, and other social media platforms to alert the press and the international community to what they consider the repression of free speech by the Cuban government.

As more international attention came to the incident, police and state officials showed no signs of yielding to the demands and cordoned off the block where the activists were staging their protest. preventing many friends, family, and supporters from entering the house.

State-run media outlets, including the Twitter account of President Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, have called the the MSI participants in an “imperialist reality show.”

San Isidro: an imperialist reality show. An imperialist show to destroy our identity & subjugate us again; those plans shall be crushed.#SomosCuba #SomosContinuidad https://t.co/QfR6q8hPdX

— Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez (@DiazCanelB) November 29, 2020

Over the weekend, police entered the MSI headquarters under the premise that the demonstration was a COVID-19 risk and momentarily ended the protest.

Luis Manuel Otero was detained and put in the hospital but no one was able to see him or verify his health condition. Rapper and MSI member Maykel Castillo Pérez continued his hunger strike at home but was also refused visitors or an independent medical examination, said Aminta D’Cárdenas, a member of the group.

“This is part of a policy of racism —the movement is predominantly Black— and systemic repression that the Cuban government exerts on its citizens,” said Abel González, a MSI supporter now living in New York City. “The protesters have been stripped of all legal avenues to claim their rights. Like many Black slaves from the past, they have only been left to pawn their bodies as a guarantee of their freedom with this strike.”

The MSI hunger strike marks a new level of protest from Cuban artists who have used performance art in the past as a tool of dissidence.

“What is really our level of commitment? To what extent are we willing to sacrifice to achieve a change in our country?” said Luis Restoy, a Cuban artist living in New York and supporter of MSI. “The MSI has shown its opposition to the Cuban totalitarian state through cultural actions that have become triggers and calls for attention to the dictatorial policies implemented by the Cuban government.”

It has been a hard week for the Cuban artist community abroad. Restoy has had trouble eating and sleeping while his friends have starved themselves back home, but the MSI are opening people’s eyes to the system of oppression that Cubans have been living in their whole lives, he said.

The artist community in Cuba has become more vocal since the implementation of Decree 349 in December 2018. The law restricts all public art without the strict approval of the ministry of culture, thus censoring artistic free expression.

Amnesty International has called the law a “dystopian prospect for Cuba’s artists.”

Over the weekend, protesters demonstrated outside the Cuban ministry of culture and a Saturday demonstration in the Little Havana neighborhood of Miami were held in solidarity of MSI. The Associated Press reported that the there has been an agreement for dialogue and tolerance between the Cuban government and the artists who have been protesting.

The protest movement is stretching into another week and Michel Matos hopes that more people will show their support.

“The people have a lot of devotion but there is a lot of fear. We’re not leaving the street. We are not asking people to leave the street, even though it’s dangerous, it is our right as citizens,” Matos said.

***

More than a dozen members of the San Isidro Movement who oppose the Cuban government stood up to the Communist regime for 10 days last month by locking themselves inside a dilapidated house in Old Havana.

Some of the 14 San Isidro Movement members who were protesting their arrests while demanding the release of Daniel Solís, a rebellious rapper who the regime sentenced to eight months in prison for “disrespect,” also went on a hunger and thirst strike.

A policeman entered Solís’ house and insulted him while he was doing a Facebook Live video in which he expressed his support for President Trump. Solís during his broadcast used homophobic insults which prompted members of Cuba’s LGBTQ community to distance themselves from him. The rapper in the last video he uploaded to his social media networks apologized for his comments.

Solís was convicted without due process, and the San Isidro Movement members consider his incarceration an injustice. His release was their main demand to the government, although they also sought the closure of stores that sell basic products in U.S. dollars, a currency to which the vast majority of Cubans do not have access.

State security agents and police surrounded the house during the 10-day strike, and did not allow anyone inside. They even attacked it one night, destroying part of the front gate.

The police on Nov. 26 forcibly ended the peaceful protest under the pretext of possible exposure to the coronavirus from abroad. Carlos Manuel Alvarez, a journalist who circumvented security and entered the San Isidro Movement’s headquarters to show his solidarity, had arrived from Mexico and authorities said they needed to test him for the coronavirus again.

The activists were brought to police stations after their expulsion, and they remained in custody for hours. Authorities beat them and later released them to their respective homes. San Isidro Movement leader Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, who did not agree to go with a fellow activist, remained in custody.

His whereabouts were unknown for several days, until activists learned he was hospitalized against his will. Otero continued his hunger strike for several more days until he ended it to continue the fight for Solís “and all the brothers imprisoned and abused by this waning regime.

The San Isidro Movement activists remain under state security surveillance.

‘They mess with one of us, they mess with all of us’

Osmel Adrián Rubio Santos, a gay man who is just 18-years-old, joined the San Isidro Movement in September, but he had already begun his fight for human rights on the Communist island.

Rubio told the Washington Blade in an exclusive interview that he joined the movement because he wanted to peacefully protest Solís’ arrest and conviction.

“We say that when they mess with one of us, they mess with all of us,” said Rubio, who added he has never felt discriminated against within the group.

Rubio, like the rest of his counterparts, joined the hunger strike when the police prevented a neighbor from bringing food to the San Isidro Movement headquarters. Authorities later allowed food into the house, but the activists decided to continue their hunger strike as a way to exert more pressure for Solís’ release.

Rubio did not eat anything for three days. He ended the hunger strike due to what he described as his “delicate state of health.” Rubio told the Blade he thought he was going to die when he felt a sharp pain in his liver.

“I was, however, firm in knowing that I was fighting for my freedom and that of my country,” he added.

Rubio said San Isidro Movement members tried to stay positive and maintain a cheerful spirit, despite the constant threats and repression they faced.

“It was a wonderful few days,” he said. “I could see what a free Cuba would be like, because there were all kinds of people there, from a gay man like me to a Muslim.”

Rubio said government supporters participated in a variety of actions in a desperate attempt to end the protest.

“The first attack we received was one day at 4 in the morning,” he said. “State security went up on the roof to pour acid on us and subsequently poisoned the water in (our) headquarters and in three other houses. They also threw acid under the door in order to suffocate us.”

A neighbor began to break down the house’s door with a hammer after he was unable to get Otero to leave.

“They began to throw several broken bottles at him through the window,” Rubio told the Blade. “Luis Manuel was injured in the face.”

Rubio said their eviction was a dark moment.

“They (the officers) kicked down the door,” he said. “They were state security officers disguised as doctors. They violently attacked us and took each of us out with blows and insults. They then took us to a police station. They kept us in a van for almost three hours and then they took us out one by one, beat us and took us to each of our homes.”

Rubio remains under surveillance 24 hours a day at his home in Havana’s Cotorro neighborhood. State security agents are posted at the door, and they prevent him from leaving. Rubio, for his part, reads to them “The Golden Age,” a children’s book that José Martí, Cuba’s national hero, wrote, and the Bible.

Rubio’s neighbors have also repudiated him. He sent the Blade a video that shows a crowd walking to the rhythm of a conga drum as they pass in front of his house.

The Cuban government through state-controlled media has also launched a smear campaign against San Isidro Movement members that seeks to present them as U.S.-funded mercenaries.

“As long as we continue to be watched, the fight will continue on social media,” lamented Rubio. “In my case, I cannot fight over the (social media) networks, because the state security blocked my phone and my line.”

‘The true revolutionaries’

Cubans who live abroad have shown their support for the San Isidro Movement in a variety of ways.

Demonstrations have taken place in front of embassies on the island and in other countries. They have also happened in D.C., Miami, Mexico City and Madrid, among other cities.

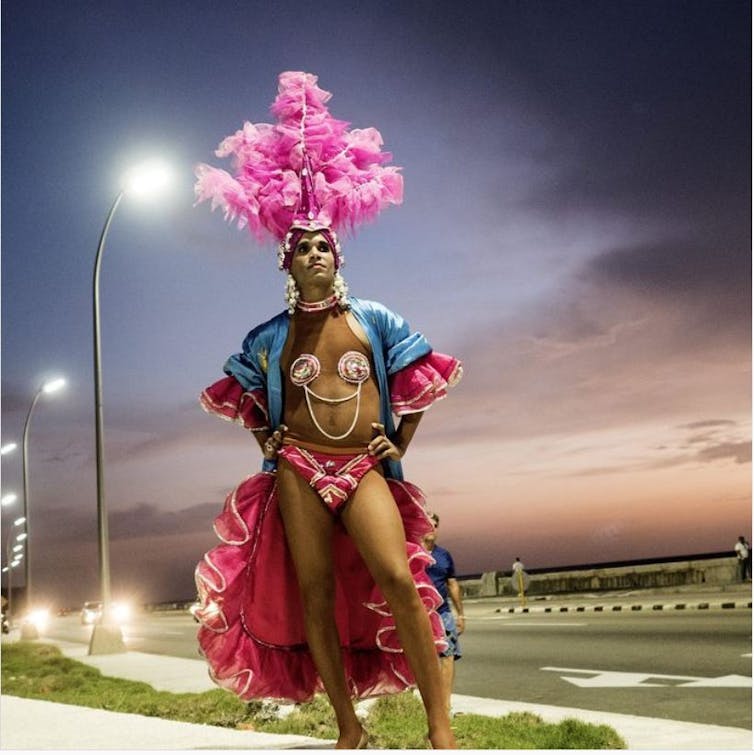

Nonardo Perea, a queer Cuban artist who now lives in exile in Spain, has been a member of the San Isidro Movement since 2018. He has used his art to denounce the dictatorship’s actions against this group of independent activists and used his social media networks to make the movement more visible.

“Demonstrations have been held in different parts of the city of Madrid, where we have been gathering a group of Cuban men and women who advocate for change in Cuba and in favor of the San Isidro Movement and of Denis Solís’ release,” Perea told the Blade from Madrid. “We will not stop taking actions to somehow create visibility for the Spanish government and the international community.”

He said the San Isidro Movement has helped him to be more creative and allowed him to successfully transition between queer art and political art.

“In some way it has helped me to evolve, to find other ways of making art,” said Perea. “After being part of the movement and having to go into exile, my life is different.”

“Somehow everything has changed. I can no longer be the same as before,” he added. “Now I can see things more clearly. I already know that those who were supposed to be revolutionaries stopped being so with their bad actions against me. The true revolutionaries are those from San Isidro. The others are henchmen, and they have proven that they can do whatever they want with your life.”

Perea, who considers himself a non-binary person, said he never felt discriminated against within the group because of his sexual orientation or gender identity.

“The group always supported my work, and somehow thanks to them my work had a certain visibility when they invited me to the Bienal 00 (an independent art festival in Havana),” he said. “I must clarify that my work is 100 percent focused on issues of the LGBTIQ community. I don’t think there was any problem with gay issues within the movement. Everyone was and is in favor of freedom, both of expression and of gender.”

Three Spanish MPs have denounced Solís’ imprisonment and have expressed their support for the San Isidro Movement. Republican and Democrat lawmakers in the U.S. have also urged the Cuban government to respect the San Isidro Movement’s demands.

Timothy Zúñiga-Brown, the U.S. Embassy in Havana’s chargé d’affaires, has responded to the San Isidro Movement’s call for economic justice and human rights on the island. The American diplomat in a message assured them that “the world is watching, the international community recognizes their peaceful protest.”

“The Cuban government has a responsibility to respect the human rights of all of its citizens,” said Zúñiga-Brown in a statement the embassy tweeted on Nov. 27.

Zúñiga-Brown in his statement also cited a quote from Nelson Mandela.

Encargado TZB: Como dijo Nelson Mandela una vez, “Estamos convencidos de que el mensaje que los huelguistas de hambre querían transmitir al Gobierno y al país ha sido transmitido”.

El gobierno cubano tiene la responsabilidad de respetar los #DDHH de todos sus ciudadanos.

— Embajada de los Estados Unidos en Cuba (@USEmbCuba) November 27, 2020

https://www.washingtonblade.com

Cuba: Solidarity for the San Isidro Movement

At the end of November 2018, activists from the Artistic Movement of San Isidro met for the first time to demonstrate in the streets of Havana and in front of the Ministry of Culture, with the aim of obtaining the repeal of the Decree 349: a law aimed at restricting the creativity of any artistic activity on Cuba. Since the beginning of the movement, our colleagues from the Taller Libertario Alfredo López in Havana have participated in those mobilizations.

Most of the activists in the campaign against Decree 349 are originally from Havana, and many of them live in the Alamar neighbourhood. The neighbourhood is known for an important alternative artistic movement and was home to the most significant hip-hop and poetry festival on the island until it was interrupted and finally cancelled by the Cuban Ministry of Culture.

The activists of this movement adopted the name of San Isidro for the support of the inhabitants of this homonymous neighbourhood, located in the oldest part of Havana, because the residents of the neighbourhood rebelled against the forces of order during an organized music concert to protest against Decree Law 349.

For the artists united against Decree 349, it was clear that the Cuban government did not want the existence of art independent of the state. The state demonstrates this with the suppression of the aforementioned hip-hop and poetry festival, and also the Havana Biennial and the Young Film Festival. Decree 349 was the official response to this type of events, and for the artists, it was a declaration of war. The government did not expect such widespread rejection in response; however, despite the peaceful manifestation of art in front of the most important institution of culture, the decree came into force on December 7, 2019.

The harassment, threats and arrests followed one another throughout the campaign, not only after the summons to the Ministry of Culture. For example, the San Isidro Movement tried to hold a collective meditation in a public park, but all the artists who participated in this meeting were surrounded by the police. Several were detained for hours.

In the eyes of the Cuban government, dissent is not recognized as a right. Anyone who protests against an official design is considered a criminal and is classified as a CR (counterrevolutionary) case. This stigma continues for the rest of one’s life.

The artist’s short time in jail demonstrated that the international repercussions had been significant and that the government was concerned about the implications of the repression. The official response was given through a television program in which the authorities justified the need to apply Decree 349. However, it was said that its entry into force would not take place immediately and that it was necessary to review and debate the regulations. For the movement, this represented a victory. But waiting for the Cuban government to publicly acknowledge a mistake is a utopia, because there is too much arrogance on their part, for fear of losing absolute control over the population.

Hunger strike and its consequences

Between November 9 and 19, authorities again arbitrarily detained and harassed large numbers of members of the San Isidro movement, often on several occasions. Members of the movement, which includes artists, poets, LGBTQI activists, academics and independent journalists, have been protesting in recent days against the imprisonment of rapper Denis Solís González.

Denis was arrested on November 9 and again on November 11. He was then tried and sentenced to eight months in prison for “contempt”: a crime incompatible with international human rights law. He is held in Valle Grande, a high-security prison on the outskirts of Havana. This arrest and subsequent sentence triggered Sain Isidro members to go on hunger and thirst strike, demanding the release of Denis Solís.

After a week of hunger and thirst strike, the Cuban police stormed the headquarters of the San Isidro Movement, with the aim of ending the protest. The police also expelled Luis Manuel Otero Alcántar and fourteen other Cubans from the headquarters of the San Isidro Movement in Havana for an alleged crime of disseminating the Covid-19 epidemic, according to Cuban state media.

The Cuban government alleged the crime of spreading the Covid-19 epidemic to arrest the artists and activists gathered at the headquarters of the San Isidro Movement. A group of Cuban artists then asked the authorities to dialogue with members of the San Isidro Movement and then listen to the young people present at the headquarters of the Ministry of Culture. The police held about 15 people under arrest for several hours. Among them were journalists, artists, and teachers who gathered to protest against repression and government policies that increasingly restrict freedom of expression. Following the arrests, writers and journalists from around the world denounced the expulsion from the headquarters and demanded the release of the detainees, which started a few hours later.

The members of the San Isidro Movement, the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and the singer Maykel Castillo (Osorbo), continue their hunger strike until the Cuban government releases Denis Solís. Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara is now in the Fajardo Hospital in Havana and continues his hunger strike, reports the official Twitter account of the San Isidro Movement. Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara refuses to go anywhere other than his home in Damasco Street in Havana, where the movement’s headquarters are located.

Additionally, Amnesty International declared Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, leader of the San Isidro movement, a prisoner of conscience and called for his release. The AI called on the Cuban government to stop harassing members of the San Isidro Movement and expressed concern about the situation of art curator Anamely Ramos, who is also under police surveillance at the home of Professor Omara Ruiz Urquiola.

Daniel Pinós

This text was originally published in Spanish by A Las Barricadas. It was machine translated and mildly edited. Any issues, get in touch: editor (at) freedompress.org.uk

Cuba’s Racial Reckoning, and What It Means for Biden

At the end of November, a group of approximately 500 Cubans staged a small protest outside the Ministry of Culture. This group, now called the N27, demanded the end to the permanent harassment directed toward a young social movement of mostly Afro-Cuban artists and musicians called the San Isidro Movement.

Like the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, the N27 protest was sparked by police brutality against Afro-Cubans. The focal incident was the arrest of rapper Denis Solís, one of San Isidro’s members. The incident was caught on a cell phone video which went viral on social media, prompting an outpouring of public dismay – and strong support for Solís and his defenders. Some backing came from the usual suspects, well-known dissident figures. But it also appears to have caught the imagination of newcomers: Artists, intellectuals, and even clergy members who have traditionally been partial to the Cuban regime.

Also like Black Lives Matter, the Cuban protest experienced an expansion of its demands. What began as a modest call for more respect for the movement’s autonomy and the liberation of Solís has now become a protest against the entire Cuban system. Meanwhile, the timing – just as a new U.S. president is about to take office – raises questions about how Washington should respond, if at all.

It’s important to understand the magnitude of what the movement is attempting to accomplish. They are challenging three of Cuba’s largest historical norms.

The first norm is the ban on group protests. In Cuba, it is never OK to protest in groups. An individual can protest solo at a party-sponsored event, at a meeting of a committee for the defense of the revolution, or even in the workplace. You can complain about corruption, bureaucracy, shoddy public services and management decisions. What you cannot do is organize a group on behalf of your demand. More than freedom of expression, the Cuban government goes after freedom of association. The moment two or more people join in protest, security forces act swiftly, decisively and often brutally. The result is that associational life in Cuba remains incipient, small and vulnerable, which is quite an exception in a region recognized worldwide as having some of the most powerful social movements in the world.

The second norm that the N27 movement is defying is the ban on complaints about the system, or more specifically, about Cuba’s system of discipline. The Cuban regime, like most mature dictatorships, has updated its system of discipline to the information age. The killings, firing squads, mass indoctrination and long-term imprisonment of its initial decades have been replaced or supplemented with public forms of character assassination, open threats to family members, careful monitoring of media posts, control of job opportunities, and short-term detentions. The N27 movement is calling for an end to this system of discipline.

The size of the protest may be micro, but its demands are now anything but. By defying these norms, the N27 could very well be going too far. After all, the ban on associations and the over-reliance on discipline are the only things keeping this ancient regime alive.

Meanwhile, the N27 movement is also taking on a third and final norm: It is mounting an attack on the system by placing the issue of racial justice front and center.

It is shocking that Cuba, a country with such a long and well-documented history of racism, has been so nonchalant about racial injustice. The Cuban Revolution, like many other Latin American regimes of the 20th century, embraced the mythology of racial equality. The thinking went: It is the Americans who are racists and segregationists; we in contrast embrace our mixed heritage. In Cuba, the myth of racial equality was reinforced by the government’s argument that capitalism is the source of racism and education, its antidote. Eliminate capitalism and provide education for all, and you solve racism.

Historically, anyone in Cuba challenging this sacrosanct discourse of racial triumph would be summarily dismissed, often quite literally. In 2013, Roberto Zurbano, a literary editor who dared to publish an op-ed in The New York Times entitled “For Blacks in Cuba, the Revolution Hasn’t Begun,” was dismissed from his job.

Of course, Zurbano was right. Racism is not tied to one type of economy or addressable with only one type of policy. And yet, Cuba has refused to move beyond this facile approach to racism. For years, the country’s leadership remained very white. It was almost as if they were saying: “Racial representation: Who needs it?”

Although things have changed a bit at the level of representation in recent years, the changes remain minor. Yes, more Black officials are now part of the leadership, but Black Cubans continue to be excluded from the new economic model, as Zurbano argued. Most jobs in the foreign sector go to white Cubans (los “presentables”, some call them). Most opportunities to migrate, and thus, to get remittances, go to white Cubans. Consequently, racism has remained disproportionately indecent.

The current protest in Cuba is certainly not the first, nor the largest, nor the most daring ever to take place in post-Soviet Cuba. In the early 2000s, the Varela project, an effort calling for democratic reforms, collected more than 11,000 signatures before its leaders were repressed or killed. Since 2003, the Ladies in White, a group of mothers, wives, and female relatives of political prisoners, have been staging marches across Cuba. They too have been arrested or harassed by government-sponsored mobs.

What is new about the N27 movement is its attempt to call out the system by also calling out the system’s racism. Like a sister movement also hoping to break in, the autonomous LGBT movement in Cuba, the N27 faces the obvious challenge of all contemporary identity politics movements: To build a cross-class societal coalition in a nation where majorities are complacent about this form of inequity. Gaining international support is also, of course, a challenge.

President-elect Joe Biden’s administration, which comes into office better informed than its predecessor about the importance of identity politics, racial justice and sexuality demands, ought to be prepared to handle this new chapter in Cuba’s history.

The choice should not be the stale debate between redoubling or removing U.S. sanctions. Biden needs to abandon the fruitless binary that has characterized the last decade of U.S. foreign policy toward Cuba. President Donald Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” produced two undesirable goals: entrenchment of both the leadership and the humanitarian crisis. And former President Barack Obama’s policy of concessions toward Cuba without a quid pro quo produced an easy pass for Cuba’s repressors. These binary approaches didn’t work.

Biden faces the opportunity to turn economic sanctions into negotiating tools. These tools need to be calibrated in response to changes by Cuban authorities, something Obama was unwilling to do. Biden also faces an opportunity to create a stronger international coalition of leftists to bring pressure on the Cuban regime, something Trump had no moral authority (or desire) to organize.

Biden could very well deliver. He seems to have enough experience with realpolitik to transform, rather than end, the sanctions regime. He also has the international credentials to build a coalition of the left, rather than just the right, to support his efforts.

—

Cuba’s San Isidro movement an ‘awakening of civil society’

In another era, the detention of a young Cuban dissident may have gone completely unnoticed. But when the rapper Denis Solís (below) was arrested by the police, he did something that has only recently become possible on the island: He filmed the encounter on his cellphone and streamed it live on Facebook, the Times reports:

The stream last month prompted his friends in an artist collective to go on a hunger strike, which the police broke up after a week, arresting members of the group. But their detentions were also caught on cellphone videos and shared widely over social media, leading hundreds of artists and intellectuals to stage a demonstration outside the Culture Ministry the next day….The marches were small, but were among the first independently organized demonstrations on the island in decades.

“It is this awakening of civil society, facilitated by the spread of the internet and social media, which is posing this challenge to the government,” said William LeoGrande, a Cuba specialist at American University. “To what extent does a political system which prides itself on control allow the kind of civil society expression that we’ve seen growing?”

The Economist podcast examines the surge of the artist-led protest movement in Cuba, where dissent on any scale is a dangerous proposition.

They Call Us Enemies of the Cuban People https://t.co/Ou37vxqbsy

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 10, 2020

Anger rather than fear is the widespread sentiment among Cubans — a constant, built-in discomfort, adds Carlos Manuel Álvarez, the author of “La Tribu,” a collection of chronicles on Cuba after Fidel Castro, and the novel “The Fallen.” We’re fed up with blind, doctrinaire zeal. Navigating Communism is like trying to cross a cobblestone road in high heels, trying not to fall, feigning normalcy. Some of us end up twisting our ankles, he writes for the Times:

Denis Solís

What the San Isidro movement epitomizes is the cry of a wounded country. The movement has become the most representative group of national civil society, bringing together Cubans of different social classes, races, ideological beliefs and generations, both from the exile community and on the island.

The group’s resistance has lasted for several years, and no one has been able to silence its members. Nor does it seem that the group endured this most recent repression in vain. The day after we were removed from the headquarters, hundreds of young people and artists gathered outside the Ministry of Culture to demand full recognition of independent cultural spaces and an end to ideological censorship in art. RTWT

Cuban historian and essayist, Rafael Rojas, told DW (above) that the Cuban government’s decision to break the dialogue with the critical artists means that from now on repression “will be more expeditious” as the security apparatus now has “the green light to act against protesters. Now they “have the green light to act against young protesters.”

Osmel Adrián Rubio Santos, a gay man who is just 18-years-old, joined the San Isidro Movement in September, but he had already begun his fight for human rights on the Communist island. Rubio told the Washington Blade in an exclusive interview that he joined the movement because he wanted to peacefully protest Solís’ arrest and conviction.

“We say that when they mess with one of us, they mess with all of us,” said Rubio, who added he has never felt discriminated against within the group.

Members of the San Isidro Movement “have become targets of continual harassment and arbitrary detentions by the regime,” said Acting Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs Ambassador Michael G. Kozak.

“But there is a broader rejection of moves to repress free expression, especially Decree Number 349, which forces artists to seek the government’s permission to perform, even in private spaces,” he added. “It also gives the regime the power to suspend any performance at will – subjecting all expressions of art in Cuba to the regime’s censorship.”

The World Movement for Democracy this week condemned Cuban authorities’ arrest of activist and artist Solís, a member of the San Isidro Movement (MSI).

The San Isidro Movement and the 27N: '2021 will bring a lot of art depending on Cuba's freedom'

Anamely Ramos recalls that 'we continue to fight' for the freedom of Denis Solís and the more than 100 political prisoners on the island.

The son of José Daniel Ferrer is threatened with eight years in prison

"This is thenth beating he receives from political police, since he was very young he has suffered heavy repression by castrocomunistic tyranny," his father said

MIAMI, USA. – After almost seven hours of arbitrary detention, José Daniel Ferrer Cantillo, son of the General Coordinator of the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), José Daniel Ferrer García, was released.

The 18-year-old revealed to CubaNet that a few yards from the headquarters of the opposition group, four State Security officers intercepted him to force him into a patrol car. However, he refused to be led in the absence of a legal document justifying detention, provoking a violent response from the officers.

"One beat me and three were holding me. They hit me on the nose, on the neck, on the face, on my head and then took me by force," Ferrer Cantillo denounced.

A video posted by UNPACU on YouTube shows a number of clothing the boy wearing at the time of his arrest.

"They had me about an hour in the corner standing and then they took me to the First Police Unit in Santiago. There I was threatened with eight years in prison for crimes they can manufacture, such as contempt and attack," he said.

The young man also assured that he will not pay the fine received, or any prior fines, as arbitrary.

"This is the umpteenth beating he receives from the political police, since he was very young he has suffered heavy repression by Castrocomunistic tyranny," his father said.

On the prison threat to Danielito, he said, "I have taught my children that torture in prison for years is worthwhile if it is the struggle for freedom of a slave and oppressed people."

Ferrer warned that, since yesterday, the operation of Ministry of the Interior (MININT) forces against UNPACU headquarters has intensified for six months.

Ferrer is currently serving a four-year home in prison sentence. Similarly, the Cuban regime maintains half a hundred members of its organization by complying with political sanctions.

The three san Isidro aquates arrested on Friday are at large

Isabel Santos González, mother of Adrián Rubio, confirmed the information to DIARIO DE CUBA.

Activists Anyell Valdés Cruz, Adrián Rubio Santos and Jorge Luis Capote Arias were released around midnight on Friday, as Isabel Santos González, Rubio's mother, told DIARIO DE CUBA.

"When he called me it was 11:05 PM, but as from 9:00PM transport is suspended by the Covid-19 they had to walk from the Vivac to Anyell's house in Los Pinos. As soon as they got here, since they were out of a phone, they called me. I spoke to all three of them last night at twelve o'clock," Gonzalez said.

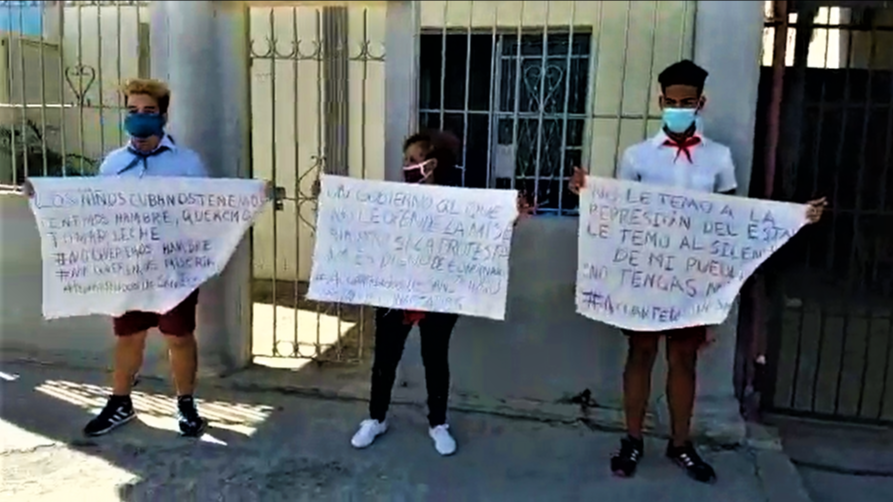

The three activists, who are part of the San Isidro quartering group, were arrested on Friday afternoon for performing in the middle of the street protesting the conditions of scarcity and political indoctrination in which many minors live in the country.

The detention procedure was the same one that repressive bodies have used against other activists, artists, journalists and opponents. He started with a guy who was filming the scene and reproached passers-by that why instead of just looking at the activists they weren't yelling "counter-reliefs."

"When they were arrested in La Palma we didn't know where they were. I called Central Police at 5:00PM, although they had been arrested at 1:22PM, because someone else was calling earlier. That person was told they weren't reported yet. I was told they were being held in Capri on charges of property abuse," Adrián Rubio's mother told.

"Anyell's daughter went to Capri, and by the time she arrived she saw how all three of them were being taken out. They told him they were going to be taken to the Vivac for public disorder," he added.

"At 11:05 it was that Adrián called me to tell me that they had been released. He told me they didn't beat them, but they didn't give them water or food either. They threatened them, my son was told they were going to throw him 30 years, that kind of intimidation they use," he concluded.

Comments

Post a Comment